Making Gaussian Splats smaller

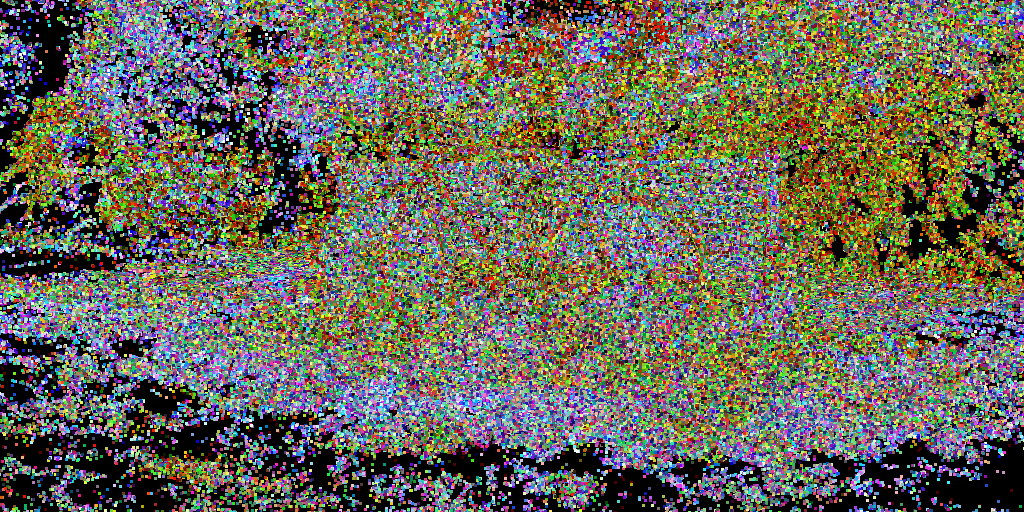

In the previous post I started to look at Gaussian

Splatting. One of the issues with it, is that the data sets are not exactly small. The renders look nice:

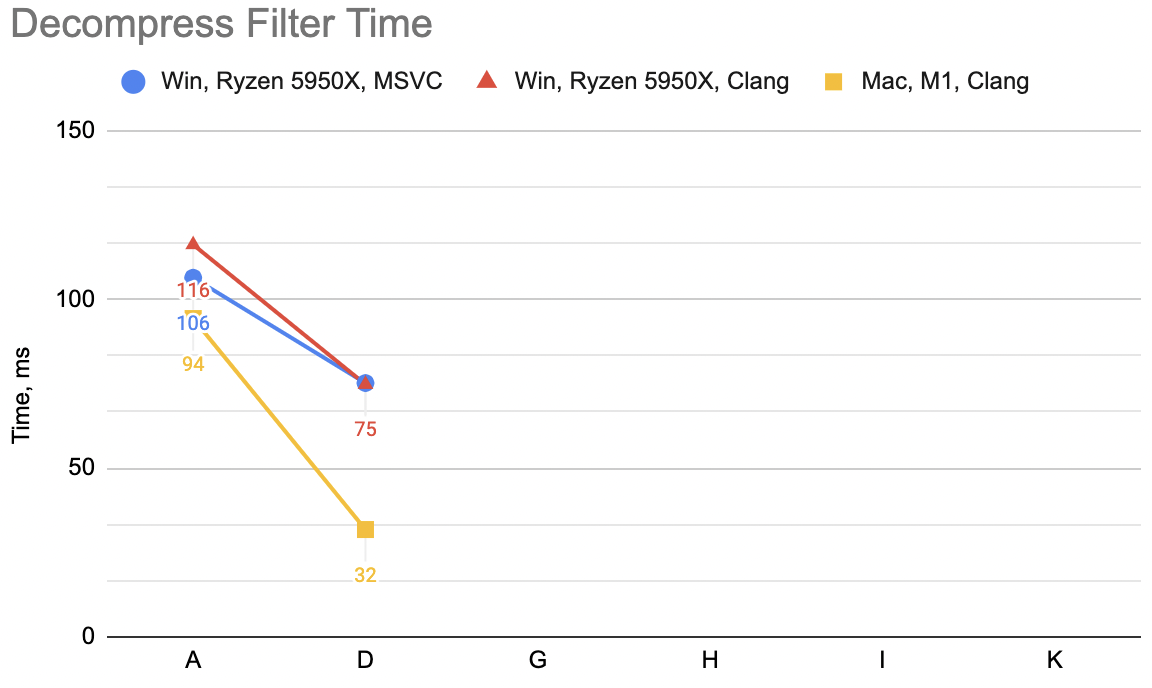

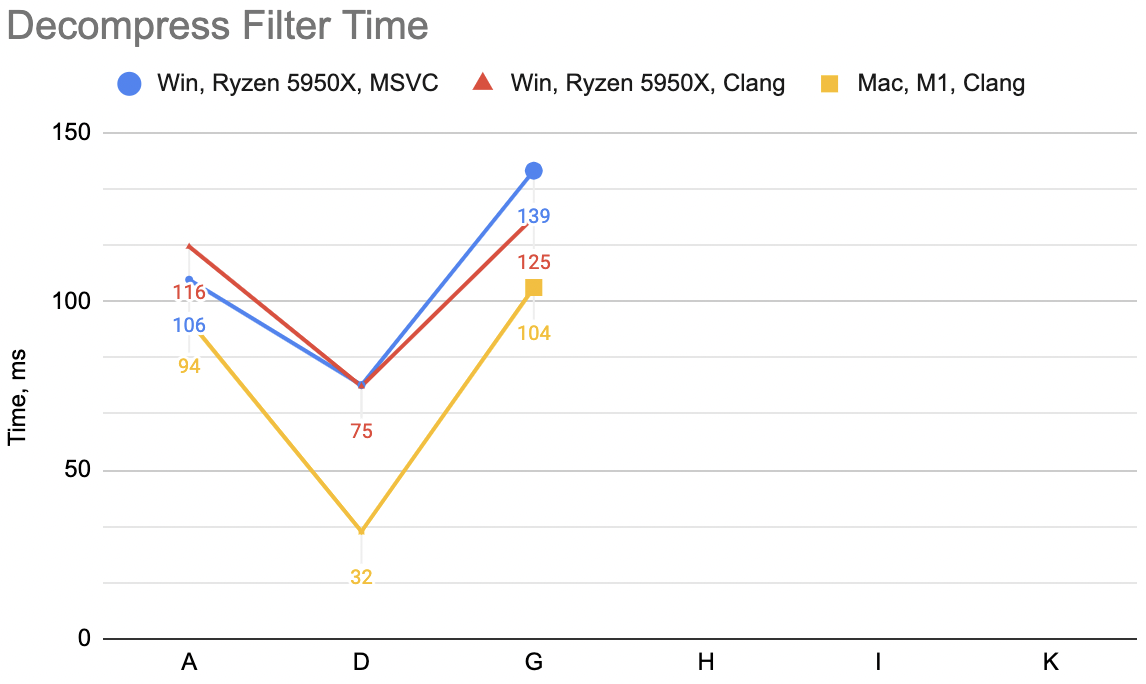

But each of the “bike”, “truck”, “garden” data sets is respectively a 1.42GB, 0.59GB, 1.35GB PLY file. And they are loaded pretty much as-is into GPU memory as giant structured buffers, so at least that much VRAM is needed too (plus more for sorting, plus in the official viewer implementation the tiled splat rasterizer uses some-hundreds-of-MB).

I could tell you that I can make the data 19x smaller (78, 32, 74 MB respectively), but then it looks not that great.

Still recognizable, but really not good (however, the artifacts are not your typical “polygonal mesh rendering at low

LOD”, they are more like “JPG artifacts in space”):

However, in between these two extremes there are other configurations, that make the data 5x-10x smaller while looking quite okay.

So we are starting at 248 bytes for each splat, and we want to get that down. Note: everywhere here I will be exploring both storage and runtime memory usage, i.e. not “file compression”! Rather, I want to cut down on GPU memory consumption too. Getting runtime data smaller also makes the data on disk smaller as a side effect, but “storage size” is a whole another and partially independent topic. Maybe for some other day!

One obvious and easy thing to do with the splat data, is to notice that the “normal” (12 bytes) is completely unused. That does not save much though. Then you can of course try making all the numbers be Float16 instead of Float32, this is acceptably good but only makes the data 2x smaller.

You could also throw away all the spherical harmonics data and leave only the “base color” (i.e. SH0), and that would

cut down 75% of the data size! This does change the lighting and removes some “reflections”, and is more

visible in motion, but progressively dropping SH bands with lower quality levels (or progressively loading

them in) is easy and sensible.

So of course, let’s look at what else we can do :)

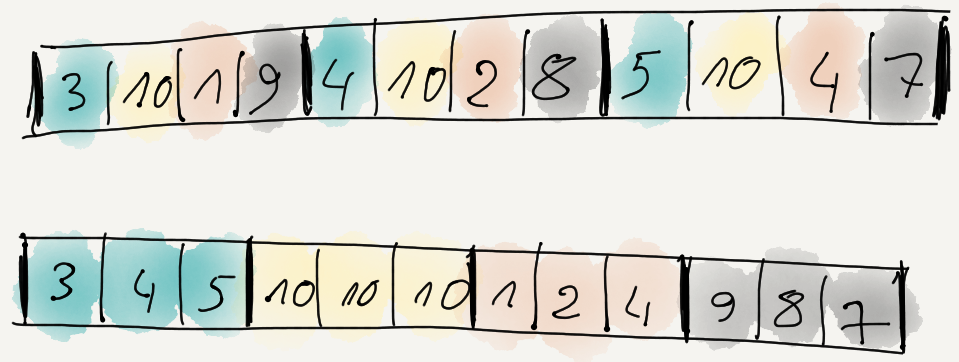

Reorder and cut into chunks

The ordering of splats inside the data file does not matter; we are going to sort

them by distance at rendering time anyway. In the PLY data file they are effectively random

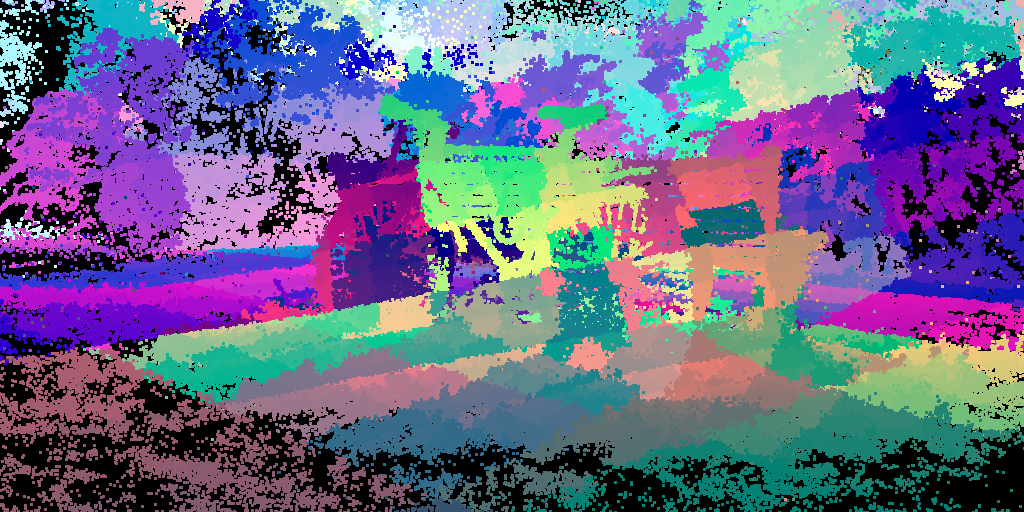

(each point here is one splat, and color is gradient based on the point index):

But we could reorder them based on “locality” (or any other criteria). For example, ordering them in a

3D Morton order, generally, makes nearby points in space be near

each other inside the data array:

And then, I can group splats into chunks of N (N=256 was my choice), and hope that since they would generally

be close together, maybe they have lower variance of their data, or at least their data can be somehow represented

in fewer bits. If I visualize the chunk bounding boxes, they are generally small and scattered all over the scene:

This is pretty much slides 112-113 of “Learning from Failure” Dreams talk.

Future work: try Hilbert curve ordering instead of Morton. Also try “partially filled chunks” to break up large chunk bounds, that happen whenever the Morton curve flips to the other side.

By the way, Morton reordering can also make the rendering faster, since even after sorting by distance the nearby points are more likely to be nearby in the original data array. And of course, nice code to do Morton calculations without relying on BMI or similar CPU instructions can be found on Fabian’s blog, adapted here for 64 bit result case:

// Based on https://fgiesen.wordpress.com/2009/12/13/decoding-morton-codes/

// Insert two 0 bits after each of the 21 low bits of x

static ulong MortonPart1By2(ulong x)

{

x &= 0x1fffff;

x = (x ^ (x << 32)) & 0x1f00000000ffffUL;

x = (x ^ (x << 16)) & 0x1f0000ff0000ffUL;

x = (x ^ (x << 8)) & 0x100f00f00f00f00fUL;

x = (x ^ (x << 4)) & 0x10c30c30c30c30c3UL;

x = (x ^ (x << 2)) & 0x1249249249249249UL;

return x;

}

// Encode three 21-bit integers into 3D Morton order

public static ulong MortonEncode3(uint3 v)

{

return (MortonPart1By2(v.z) << 2) | (MortonPart1By2(v.y) << 1) | MortonPart1By2(v.x);

}

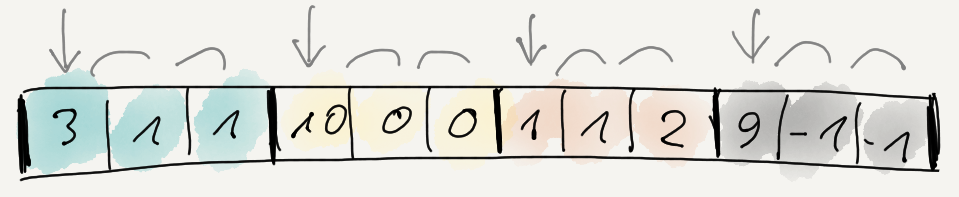

Make all data 0..1 relative to the chunk

Now that all the splats are cut into 256-splat size chunks, we can compute minimum and maximum data values of everything (positions, scales, colors, SHs etc.) for each chunk, and store that away. We don’t care about data size of that (yet?); just store them in full floats.

And now, adjust the splat data so that all the numbers are in 0..1 range between chunk minimum & maximum values. If that is kept in Float32 as it was before, then this does not really change precision in any noticeable way, just adds a bit of indirection inside the rendering shader (to figure out final splat data, you need to fetch chunk min & max, and interpolate between those based on splat values).

Oh, and for rotations, I’m encoding the quaternions in “smallest three” format (store smallest 3 components, plus index of which component was the largest).

And now that the data is all in 0..1 range, we can try representing it with smaller data types than full Float32!

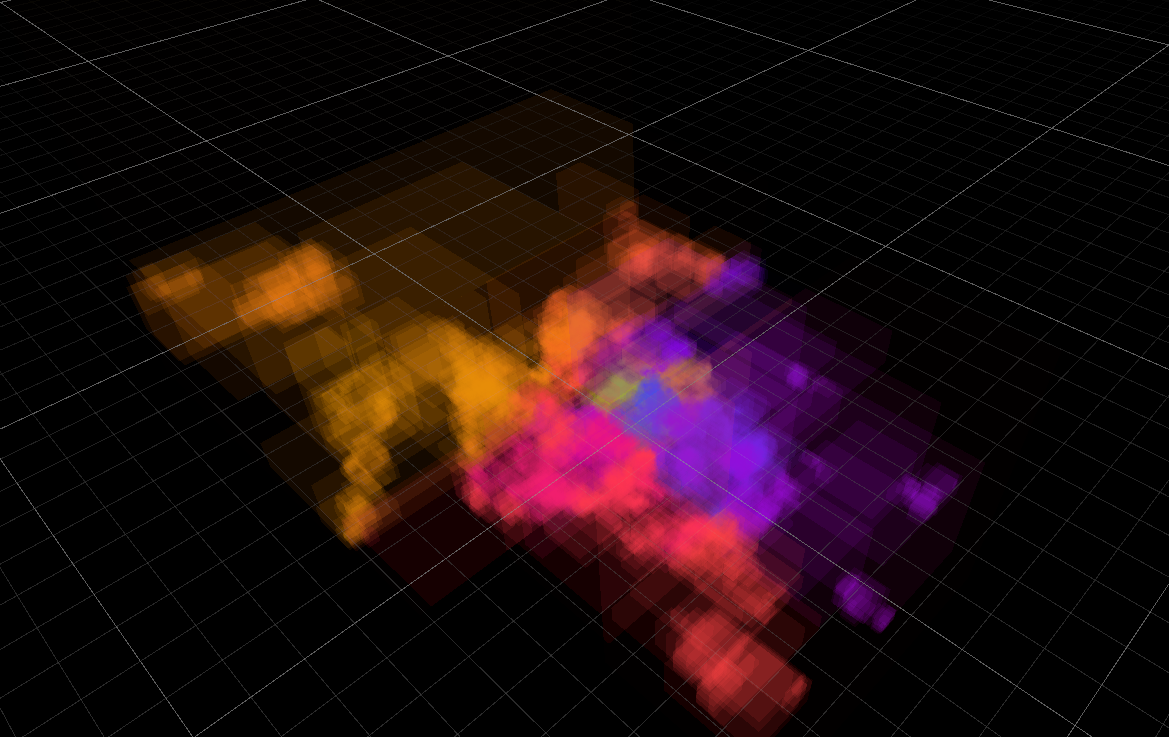

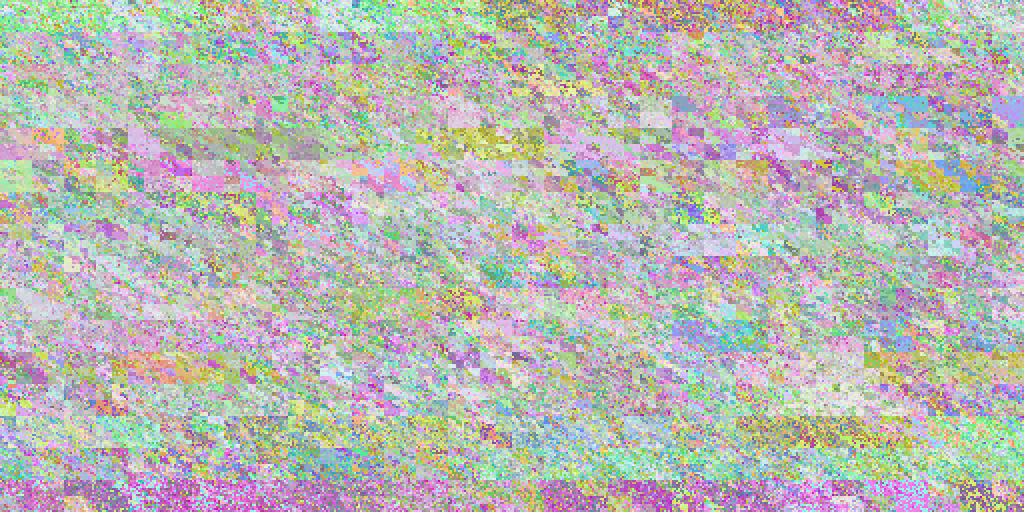

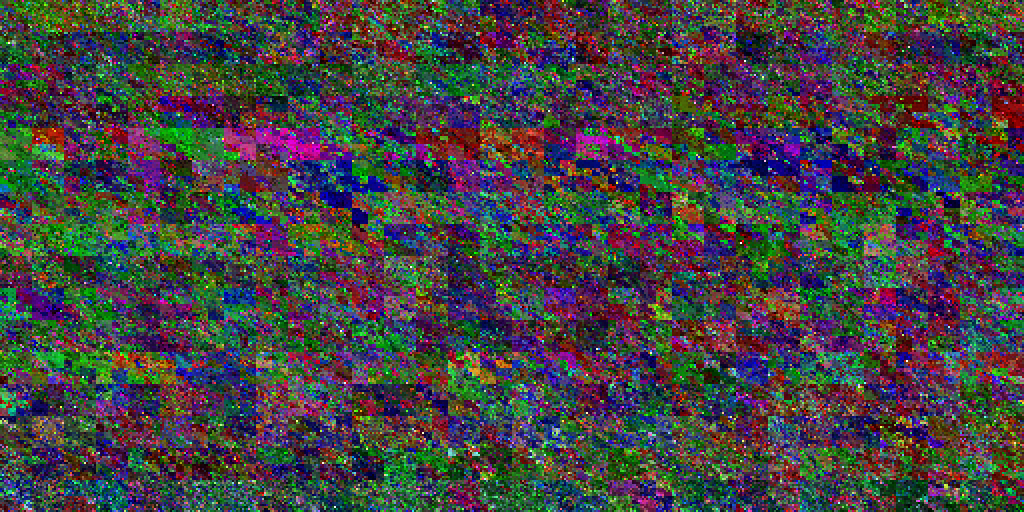

But first, how does all that 0..1 data look like? The following is various data displayed as RGB colors, one

pixel per splat, in row major order. With positions, you can clearly see that it changes within the 256 sized

chunk (it’s two chunks per horizontal line):

Rotations do have some horizontal streaks but are way more random:

Scale has some horizontal patterns too, but we can also see that most of scales are towards smaller values:

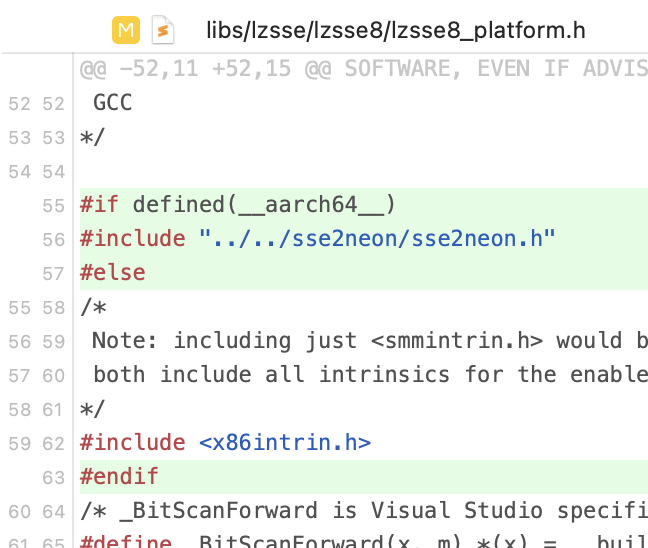

And opacity is often either almost transparent, or almost opaque:

There’s a lot of spherical harmonics bands and they tend to look like a similar mess, so here’s one of them:

Hey this data looks a lot like textures!

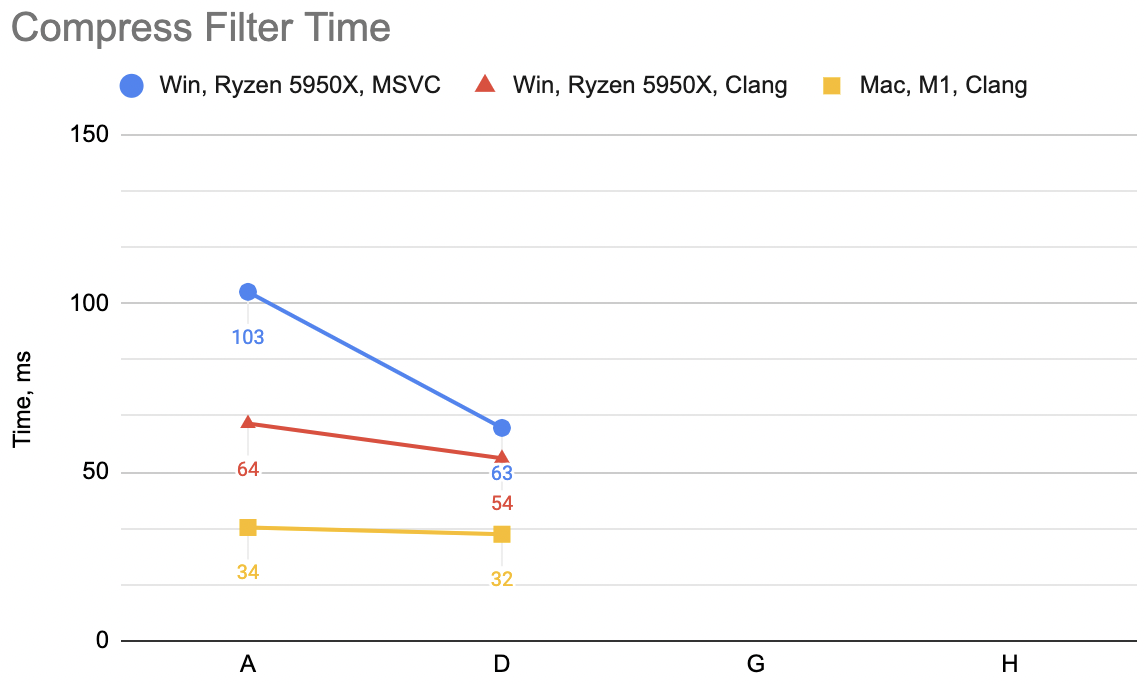

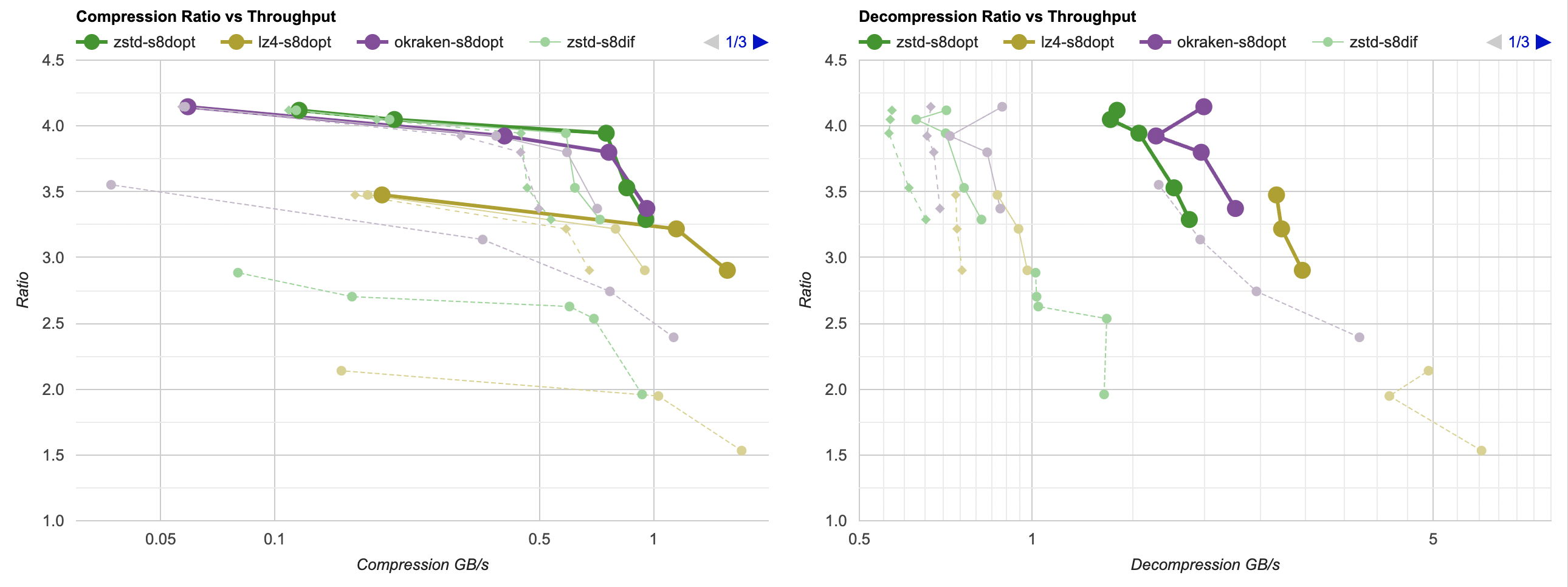

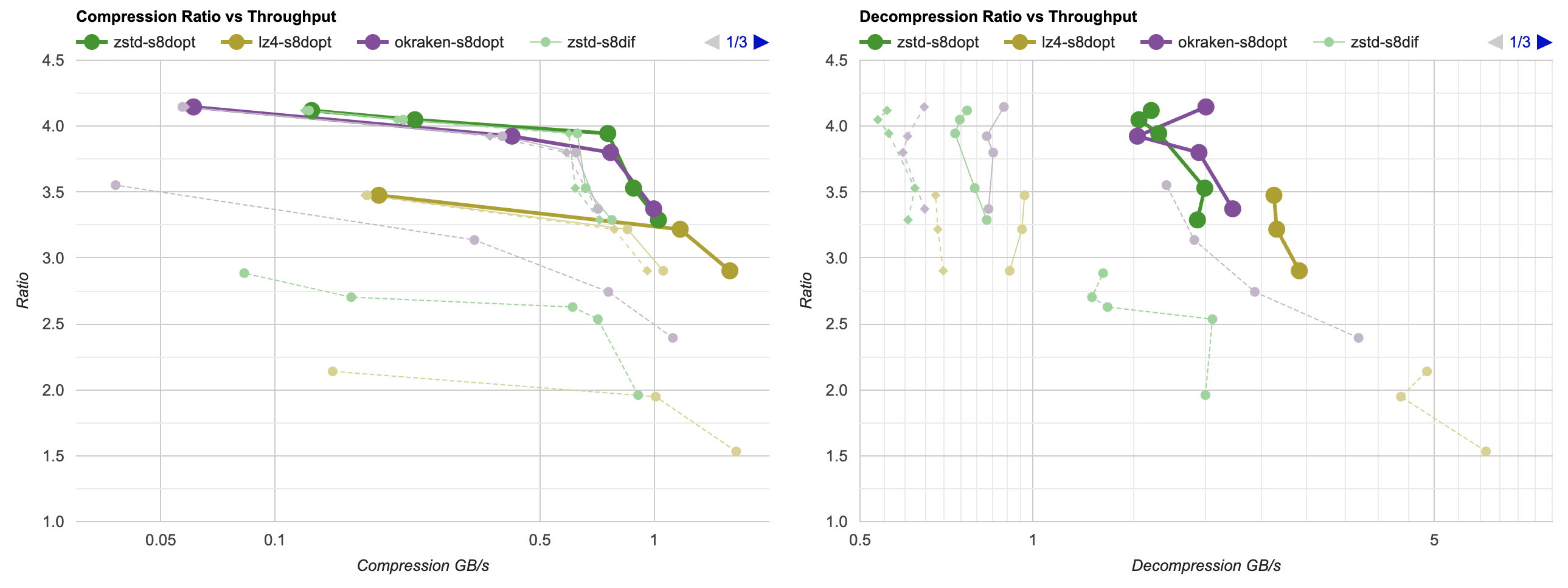

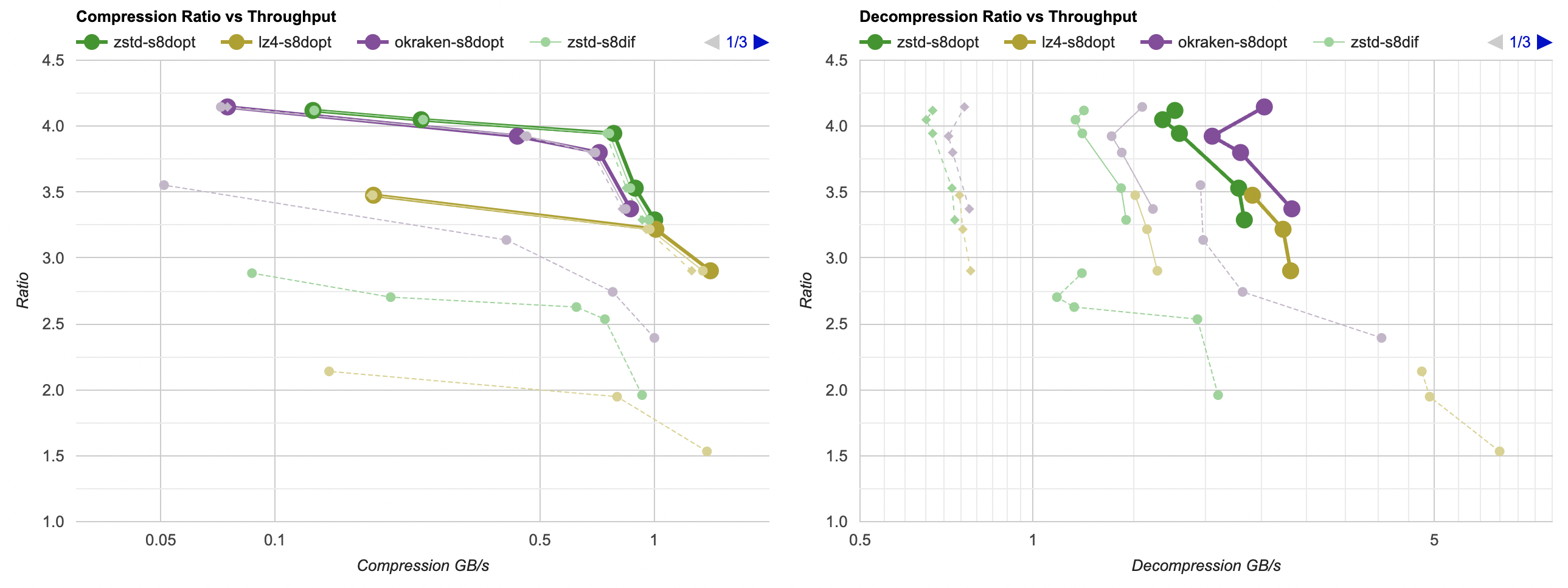

We’ve got 3 or 4 values per each “thing” (position, color, rotation, …) that are all in 0..1 range now. I know! Let’s put them into textures, one texel per splat. And then we can easily experiment with using various texture formats on them, and have the GPU texture sampling hardware do all the heavy lifting of turning the data into numbers.

We could even, I dunno, use something crazy like use compressed texture formats (e.g. BC1 or BC7) on these

textures. Would that work well? Turns out, not immediately. Here’s turning all the data

(position, rotation, scale, color/opacity, SH) into BC7 compressed texture. Data is just 122MB (12x smaller),

but PSNR is a low 21.71 compared to full Float32 data:

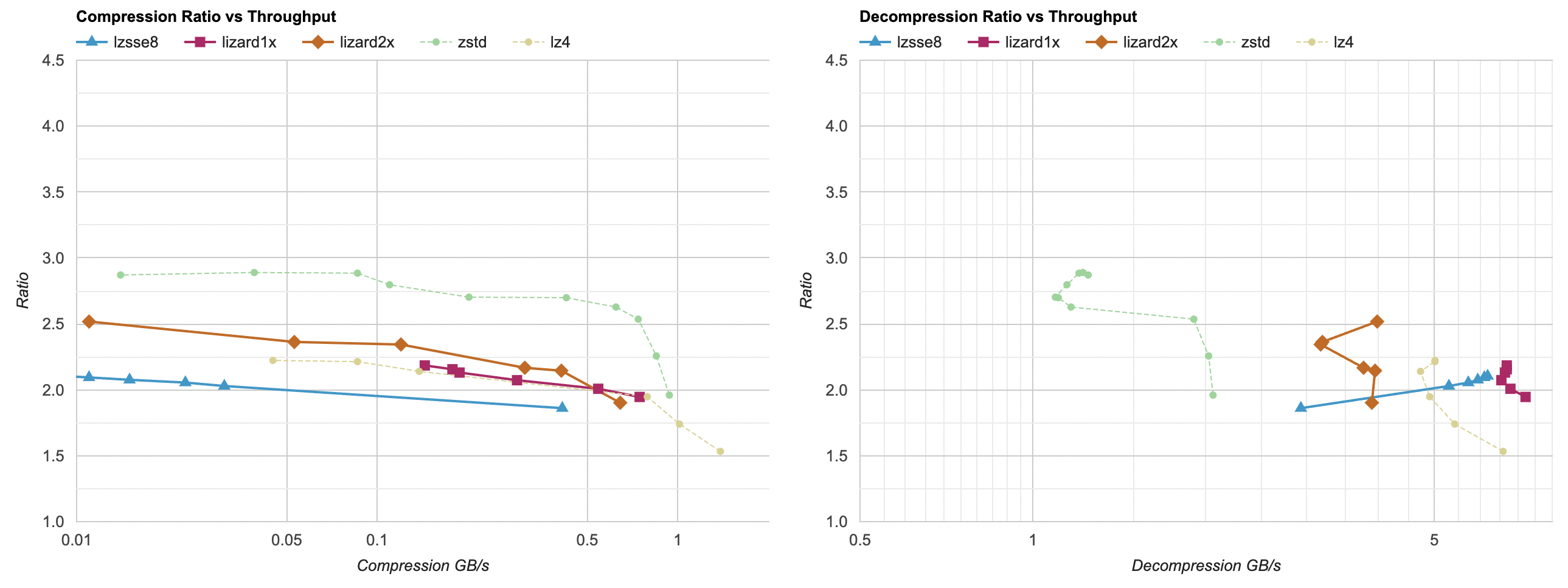

However, we know that GPU texture compression formats are block based, e.g. on typical PC the BCn compression formats are all based on 4x4 texel blocks. But our texture data is laid out in 256x1 stripes of splat chunks, one after another. Let’s reorder them some more, i.e. lay out each chunk in a 16x16 texel square, again arranged in Morton order within it.

uint EncodeMorton2D_16x16(uint2 c)

{

uint t = ((c.y & 0xF) << 8) | (c.x & 0xF); // ----EFGH----ABCD

t = (t ^ (t << 2)) & 0x3333; // --EF--GH--AB--CD

t = (t ^ (t << 1)) & 0x5555; // -E-F-G-H-A-B-C-D

return (t | (t >> 7)) & 0xFF; // --------EAFBGCHD

}

uint2 DecodeMorton2D_16x16(uint t) // --------EAFBGCHD

{

t = (t & 0xFF) | ((t & 0xFE) << 7); // -EAFBGCHEAFBGCHD

t &= 0x5555; // -E-F-G-H-A-B-C-D

t = (t ^ (t >> 1)) & 0x3333; // --EF--GH--AB--CD

t = (t ^ (t >> 2)) & 0x0f0f; // ----EFGH----ABCD

return uint2(t & 0xF, t >> 8); // --------EFGHABCD

}

And if we rearrange all the texture data that way, then it looks like this now (position, rotation, scale, color,

opacity, SH1):

And encoding all that into BC7 improves the quality quite a bit (PSNR 21.71→24.18):

So what texture formats should be used?

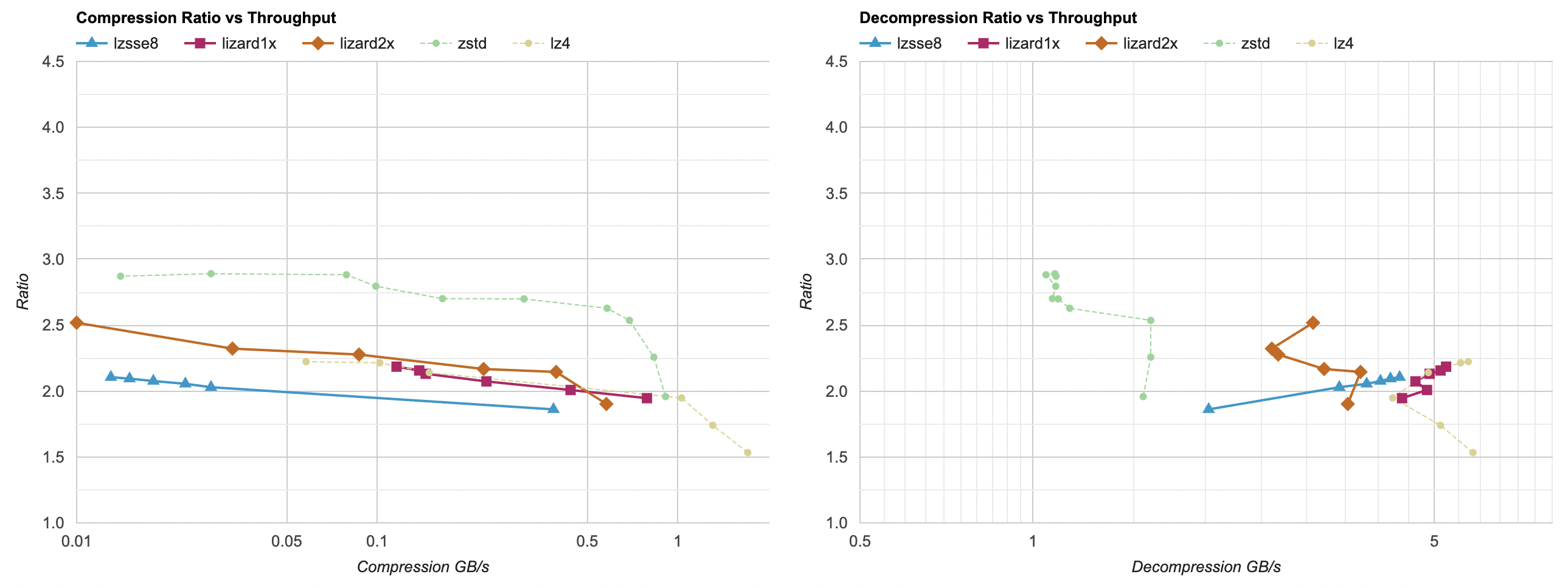

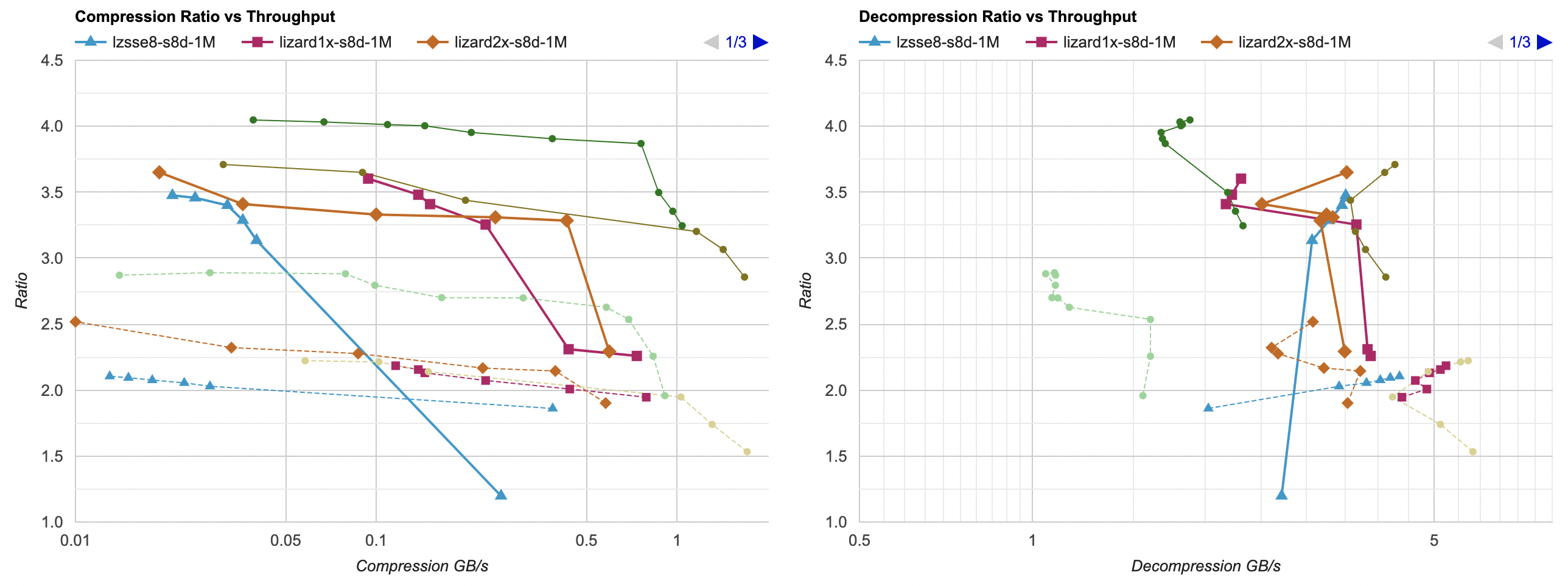

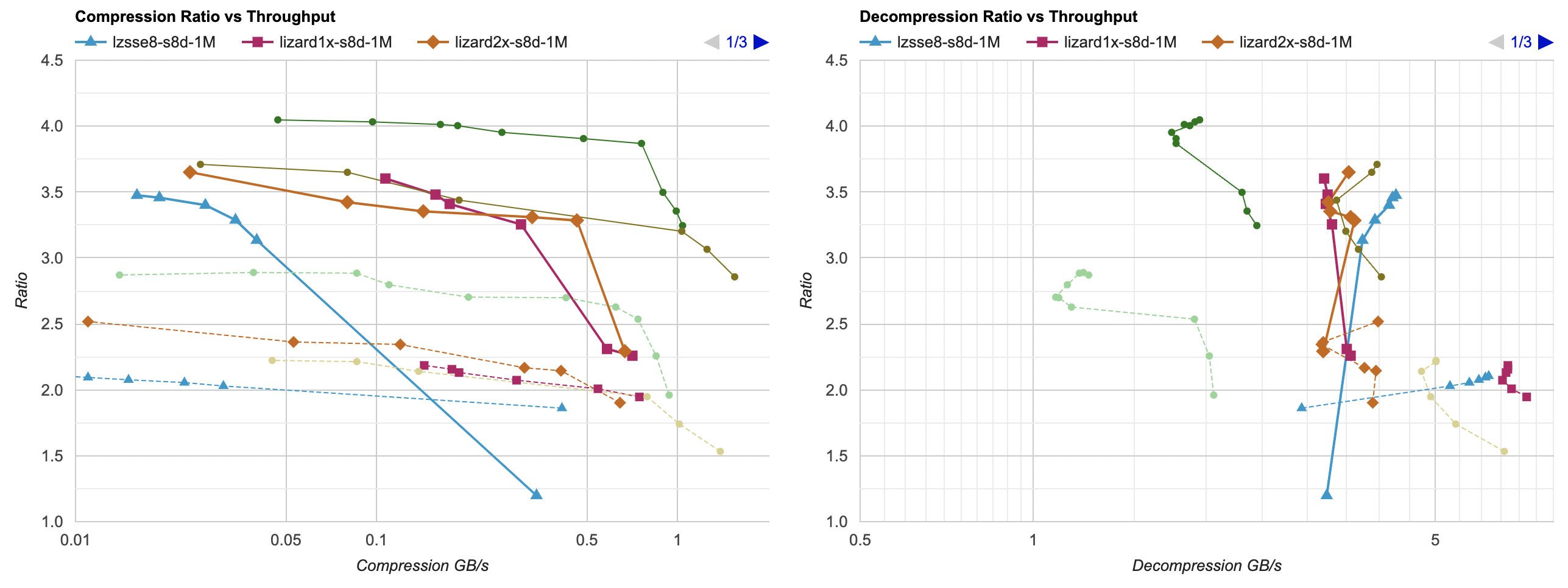

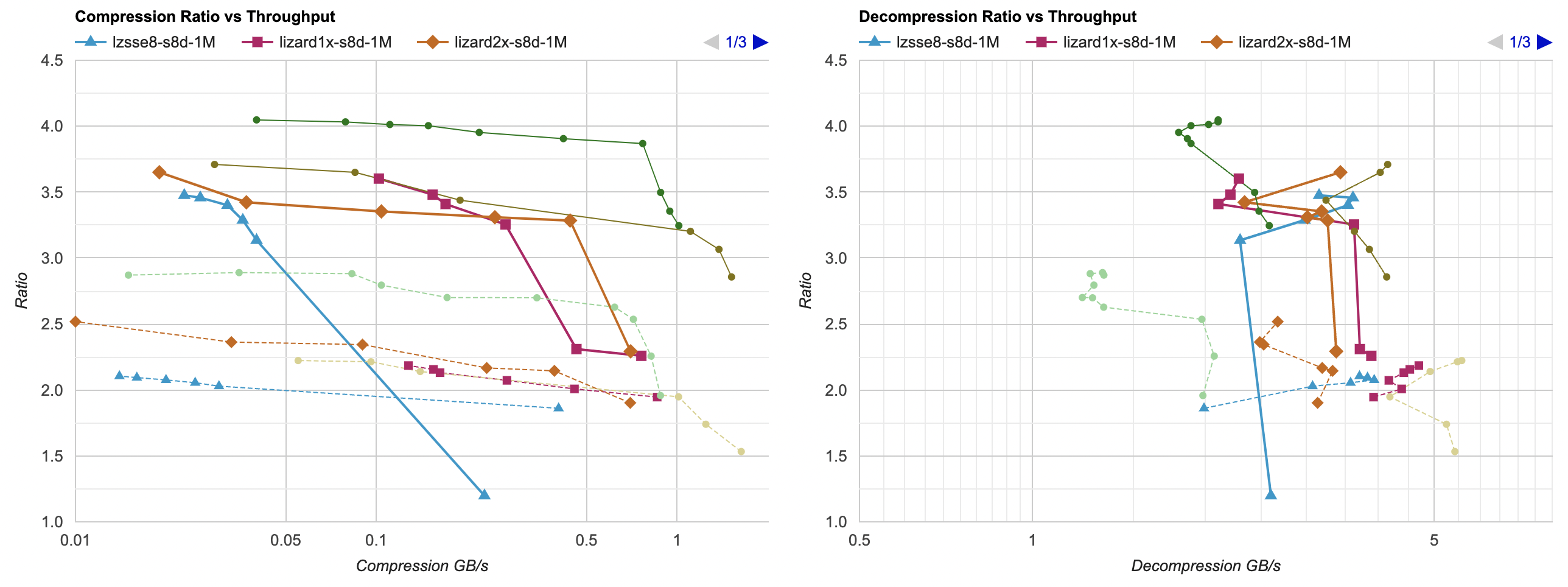

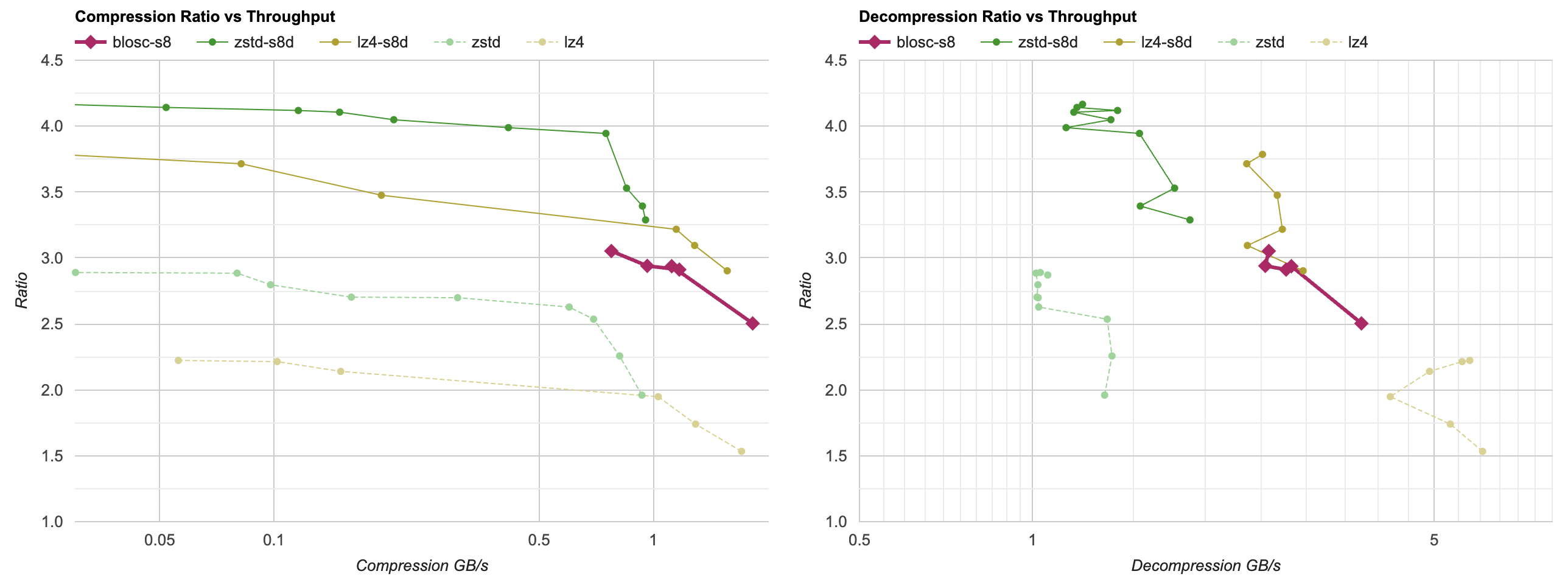

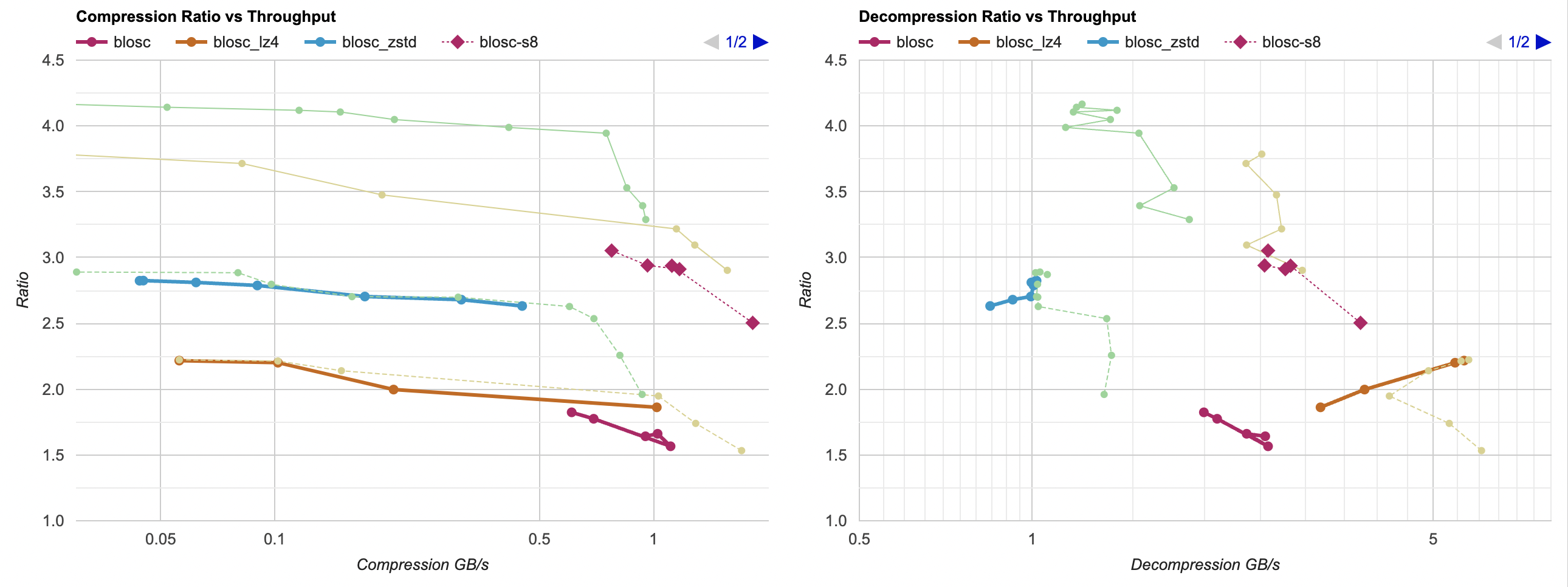

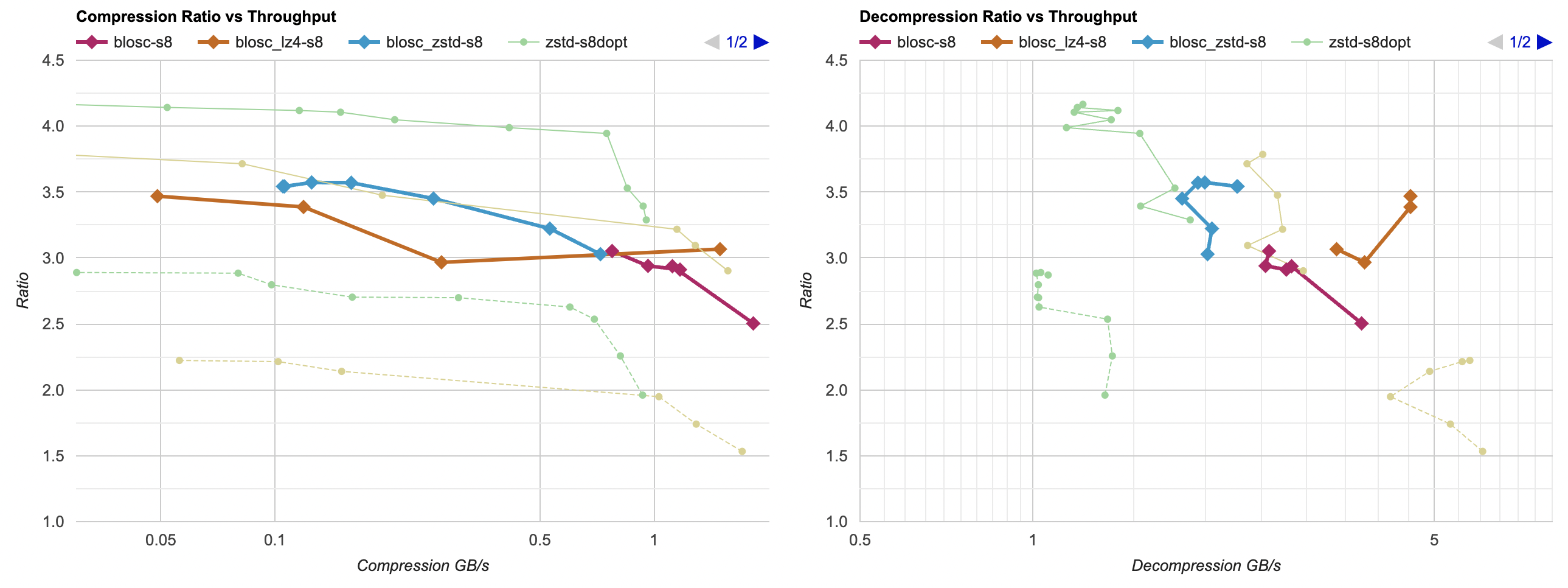

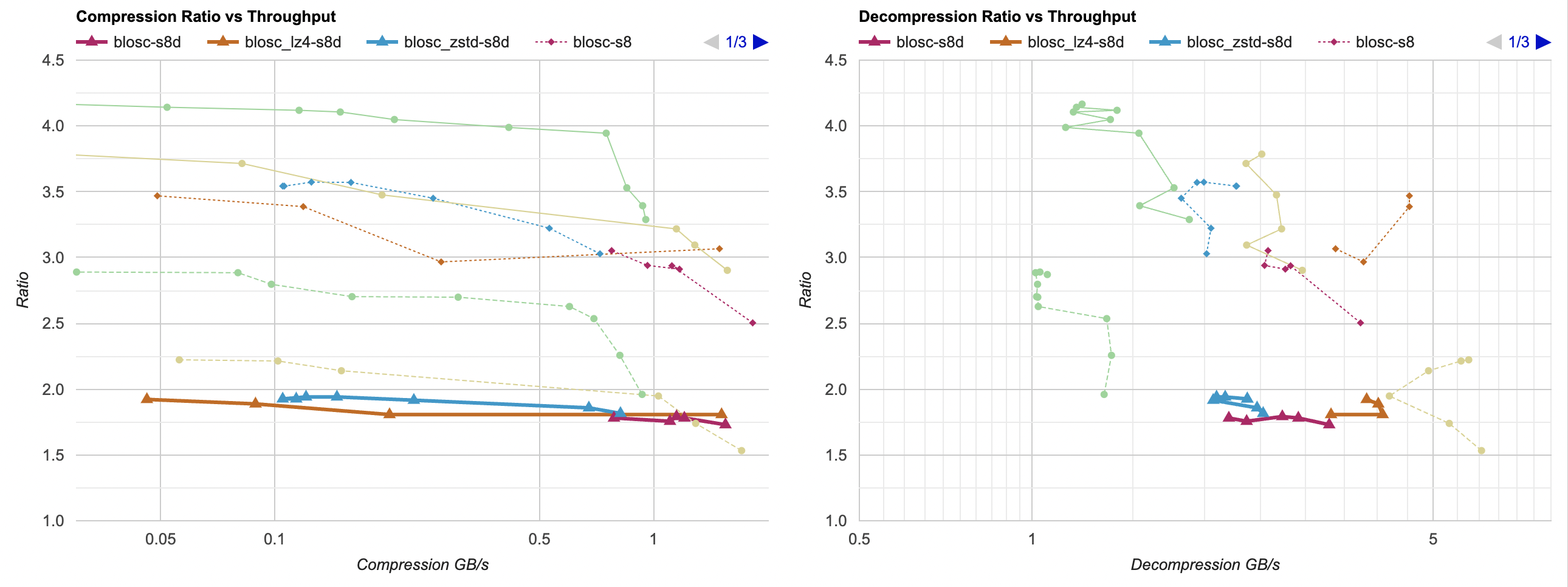

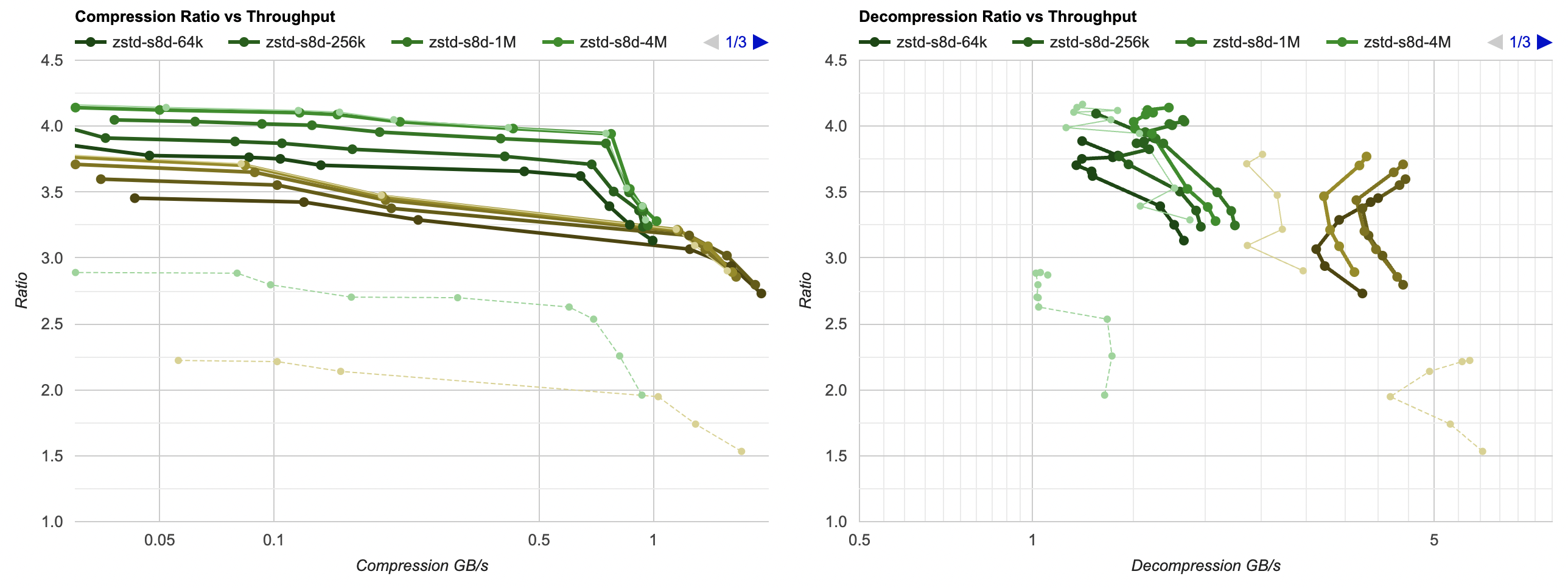

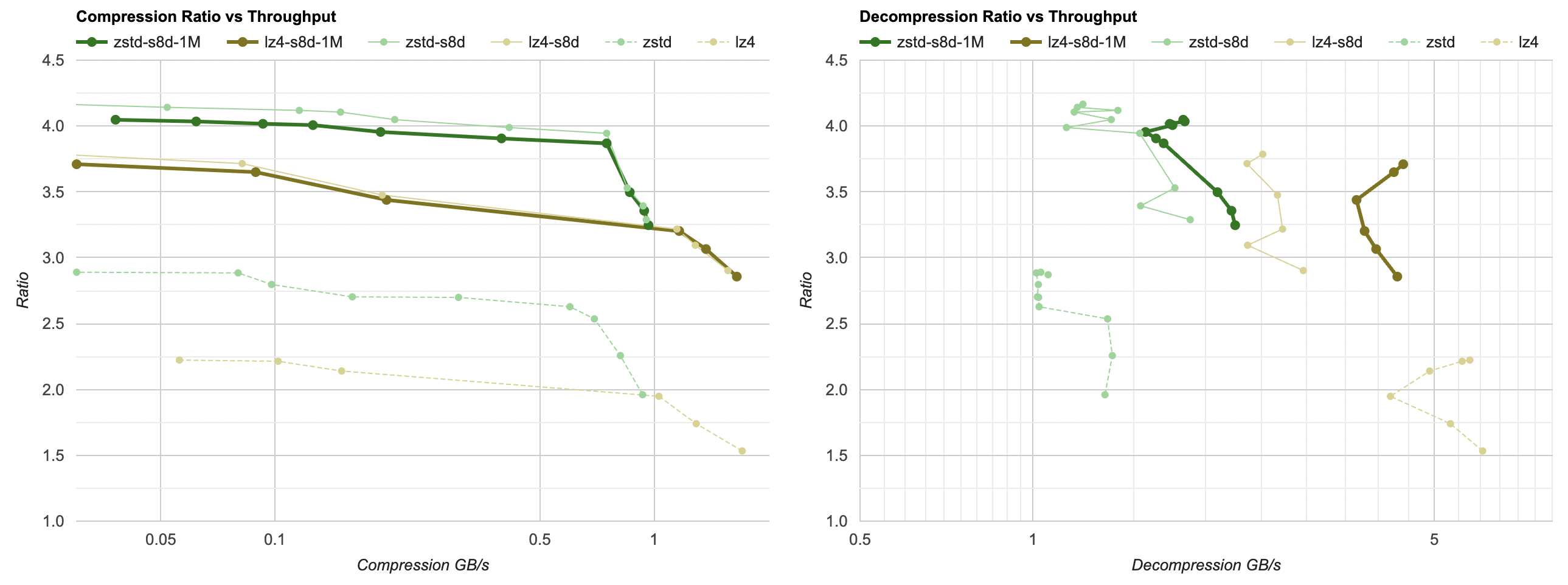

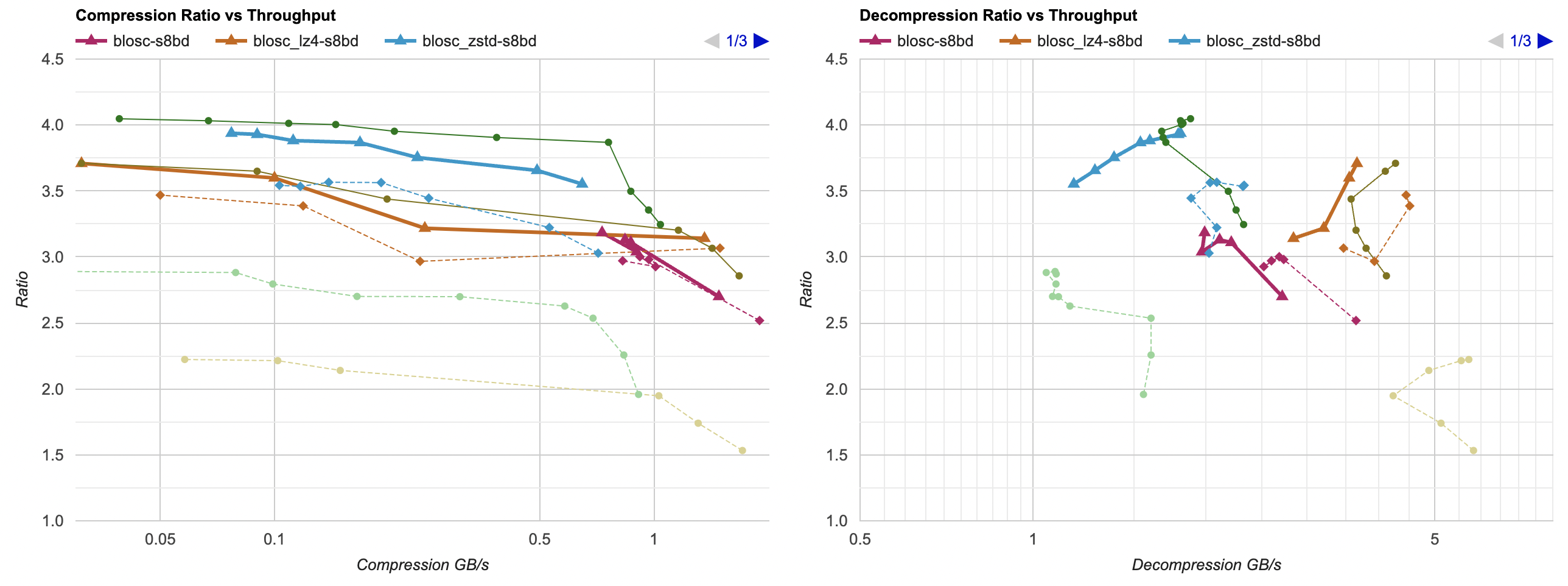

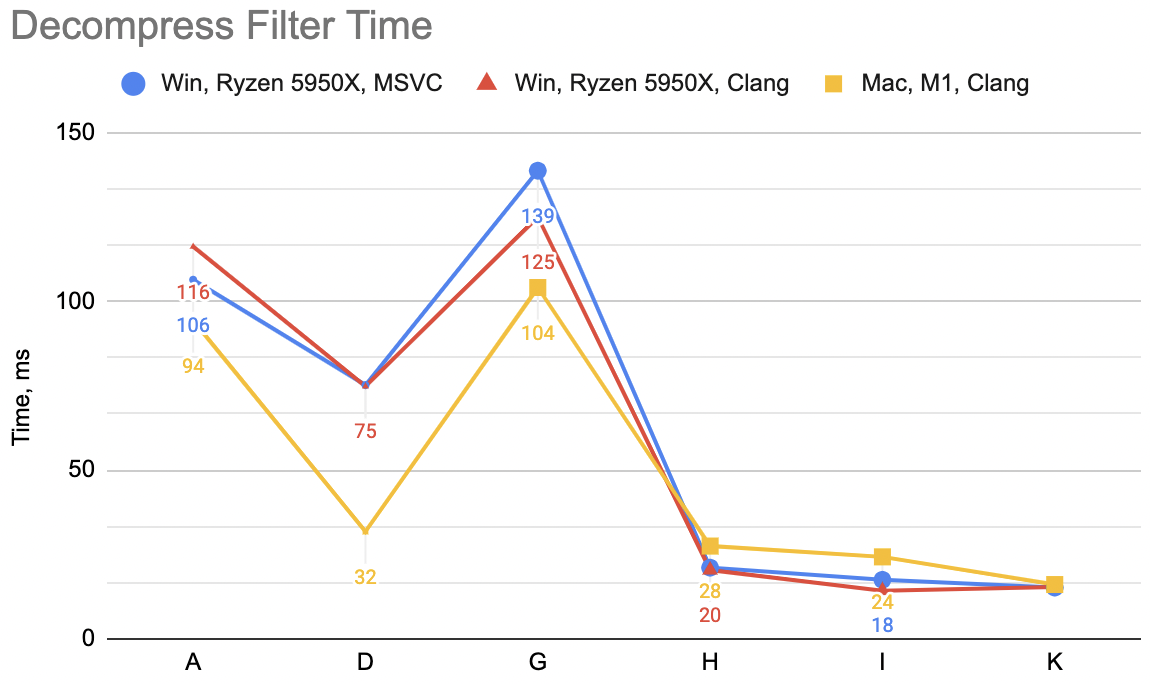

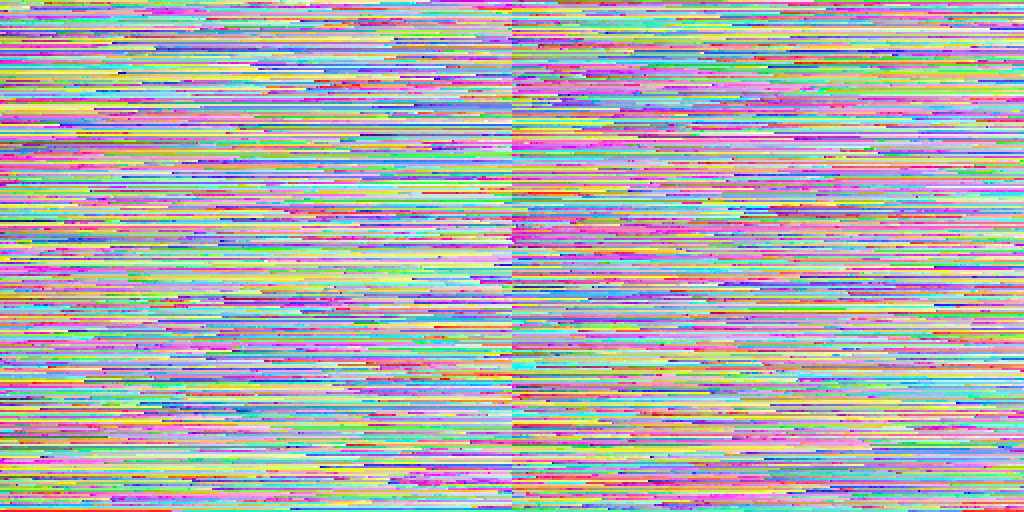

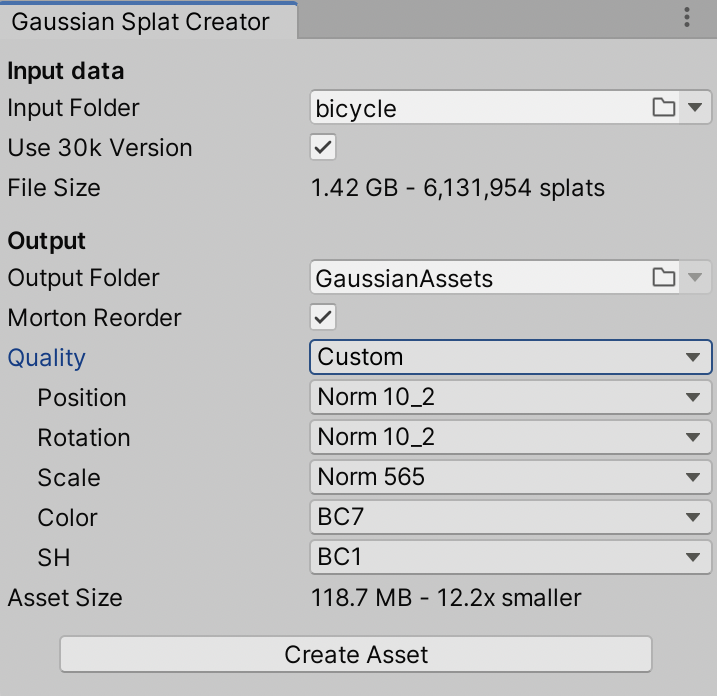

After playing around with a whole bunch of possible settings, here’s the quality setting levels I came up with.

Formats indicated in the table below:

After playing around with a whole bunch of possible settings, here’s the quality setting levels I came up with.

Formats indicated in the table below:

- F32x4: 4x Float32 (128 bits). Since GPUs typically do not have a three-channel Float32 texture format, I expand the data quite uselessly in this case, when only three components are needed.

- F16x4: 4x Float16 (64 bits). Similar expansion to 4 components as above.

- Norm10_2: unsigned normalized 10.10.10.2 (32 bits). GPUs do support this, and Unity almost supports it – it exposes the format enum member, but actually does not allow you to create texture with said format (lol!). So I emulate it by pretending the texture is in a single component Float32 format, and manually “unpack” in the shader.

- Norm11: unsigned normalized 11.10.11 (32 bits). GPUs do not have it, but since I’m emulating a similar format anyway (see above), then why not use more bits when we only need three components.

- Norm8x4: 4x unsigned normalized byte (32 bits).

- Norm565: unsigned normalized 5.6.5 (16 bits).

- BC7 and BC1: obvious, 8 and 4 bits respectively.

| Quality | Pos | Rot | Scl | Col | SH | Compr | PSNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | F32x4 | F32x4 | F32x4 | F32x4 | F32x4 | 0.8x | |

| High | F16x4 | Norm10_2 | Norm11 | F16x4 | Norm11 | 2.9x | 54.82 |

| Medium | Norm11 | Norm10_2 | Norm11 | Norm8x4 | Norm565 | 5.2x | 47.82 |

| Low | Norm11 | Norm10_2 | Norm565 | BC7 | BC1 | 12.2x | 34.79 |

| Very Low | BC7 | BC7 | BC7 | BC7 | BC1 | 18.7x | 24.02 |

Here are the “reference” (“Very High”) images again (1.42GB, 0.59GB, 1.35GB data size):

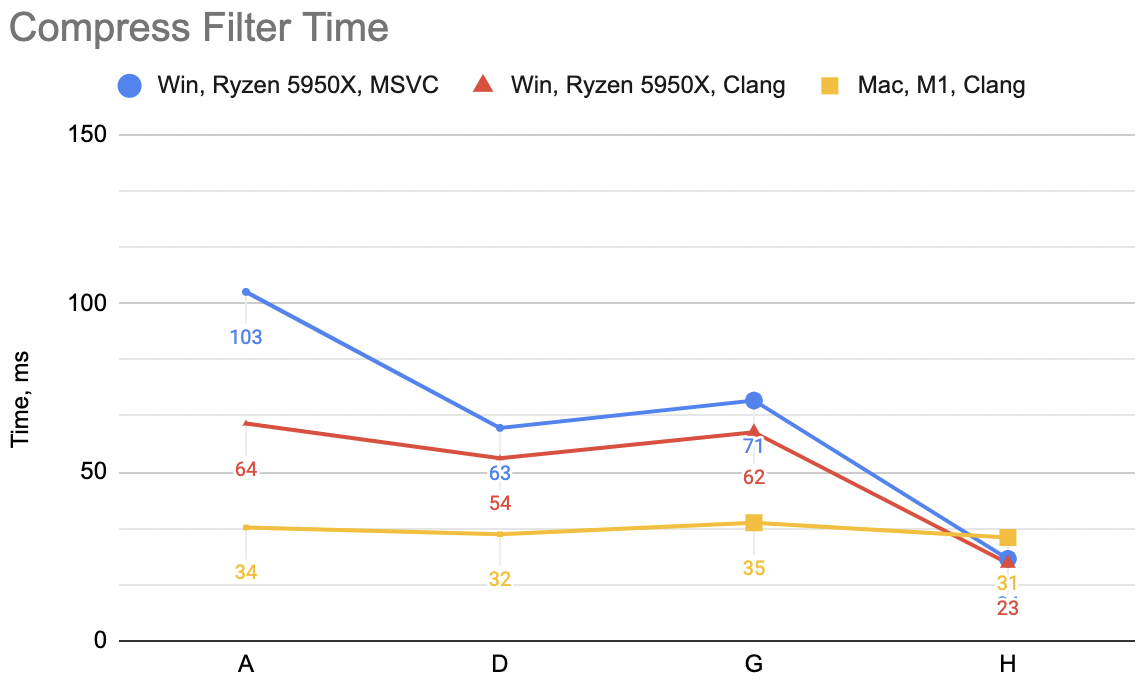

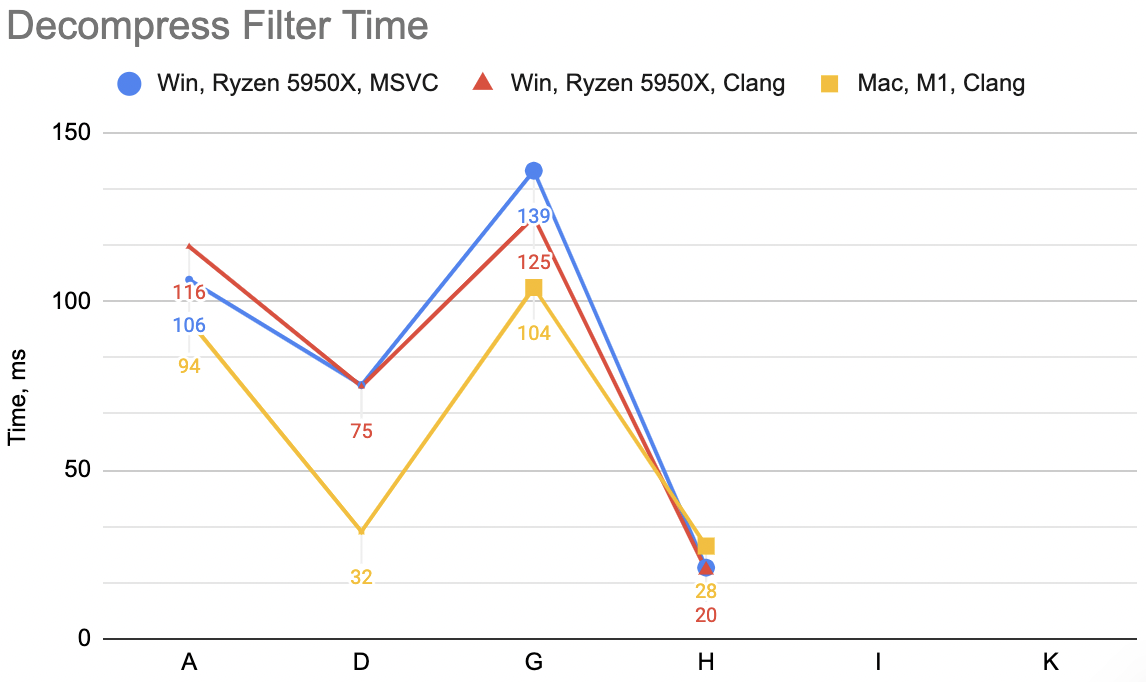

The “Medium” preset looks pretty good! (280MB, 116MB, 267MB – 5.2x smaller; PSNR respectively 47.82, 48.73, 48.63):

At “Low” preset the color artifacts are more visible but not terribad (119MB, 49MB, 113MB – 12.2x smaller; PSNR respectively

34.72, 31.81, 33.05):

And the “Very Low” one mostly for reference; it kinda becomes useless at such low quality (74MB, 32MB, 74MB – 18.7x smaller;

PSNR 24.02, 22.28, 23.1):

Oh, and I also recorded an awkwardly-moving-camera video, since people like moving pictures:

Conclusions and future work

The gaussian splatting data size (both on-disk and in-memory) can be fairly easily cut down 5x-12x, at fairly acceptable rendering quality level. Say, for that “garden” scene 1.35GB data file is “eek, sounds a bit excessive”, but at 110-260MB it’s becoming more interesting. Definitely not small yet, but way more within being usable.

I think the idea of arranging the splat data “somehow”, and then compressing them not by just individually encoding each spat into smaller amount of bits, but also “within neighbors” (like using BC7 or BC1), is interesting. Spherical Harmonics data in particular looks quite ok even with BC1 compression (it helps that unlike “obviously wrong” rotation or scale, it’s much harder to tell when your spherical harmonics coefficient is wrong :)).

There’s a bunch of small things I could try:

- Splat reordering: reorder splats not only based on position, but also based on “something else”. Try Hilbert curve instead of Morton. Try using not-fully-256 size chunks whenever the curve flips to the other side.

- Color/Opacity encoding: maybe it’s worth putting that into two separate textures, instead of trying to get BC7 to compress them both.

- I do wonder how would reducing the texture resolution work, maybe for some components (spherical harmonics? color if opacity is separate?) you could use lower resolution texture, i.e. below 1 texel per splat.

And then of course there are larger questions, in a sense of whether this way looking at reducing data size is sensible at all. Maybe something along the lines of “Random-Access Neural Compression of Material Textures” (Vaidyanathan, Salvi, Wronski 2023) would work? If only I knew anything about this “neural/ML” thing :)

All my code for the above is in this PR on github (merged 2023 Sep).

In the followup post I look at making them even smaller!