Float Compression 3: Filters

Introduction and index of this series is here.

In the previous parts we saw that using generic data compression libraries, we can get our 94.5MB data down to 33.8MB (zstd level 7) or 29.6MB (oodle kraken level 2) size, if we’re not willing to spend more than one second compressing it.

That’s not bad, but is there something else we can do? Turns out, there is, and in fact it’s quite simple. Enter data filtering.

Prediction / filtering

We saw filtering in the past (EXR and SPIR-V), and the idea is simple: losslessly transform the data so that it is more compressible. Filtering alone does nothing to reduce the data size, but (hopefully!) it decreases data randomness. So the process is: filter the data, then compress that. Decompression is reverse: decompress, then un-filter it.

Here’s some simple filters that I’ve tried (there are many, many other filters possible, I did not try them all!).

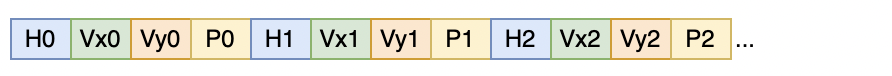

Reorder floats array-of-structures style

Recall that in our data, we know that water simulation has four floats per “element” (height, velocity x, velocity y, pollution); snow simulation similarly has four floats per element; and other data is either four or three floats per element. Instead of having the data like that (“array of structures” style), we can try to reorder it into “structure of arrays” style. For water simulation, that would be all heights first, then all x velocities, then all y velocities, etc.

Completely unoptimized code to do that could look like this (and our data is floats, i.e. 4 bytes, so you’d call these templates with a 4-byte

type e.g. uint32_t):

// channels: how many items per data element

// dataElems: how many data elements

template<typename T>

static void Split(const T* src, T* dst, size_t channels, size_t dataElems)

{

for (size_t ich = 0; ich < channels; ++ich)

{

const T* ptr = src + ich;

for (size_t ip = 0; ip < dataElems; ++ip)

{

*dst = *ptr;

ptr += channels;

dst += 1;

}

}

}

template<typename T>

static void UnSplit(const T* src, T* dst, size_t channels, size_t dataElems)

{

for (size_t ich = 0; ich < channels; ++ich)

{

T* ptr = dst + ich;

for (size_t ip = 0; ip < dataElems; ++ip)

{

*ptr = *src;

src += 1;

ptr += channels;

}

}

}

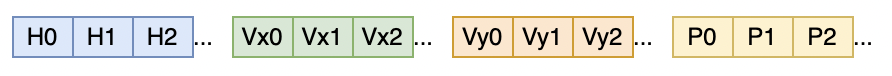

Does that help? The results are interesting (click for an interactive chart):

- It does help LZ4 to achieve a bit higher compression ratios.

- Makes zstd compress faster, and helps the ratio at lower levels, but hurts the ratio at higher levels.

- Hurts oodle kraken compression.

- Hurts the decompression performance quite a bit (for lz4 and kraken, slashes it in half). In all cases the data still decompresses under 0.1 seconds, so acceptable for my case, but the extra pass over memory is not free.

Ok, so this one’s a bit “meh”, but hey, now that the data is grouped together (all heights, then all velocities, …), we could try to exploit the fact that maybe neighboring elements are similar to each other?

Reorder floats + XOR

In the simulation data example, it’s probably expected that usually the height, or velocity, or snow coverage, does not vary “randomly” over the terrain surface. Or in an image, you might have a color gradient that varies smoothly.

“But can’t data compressors already compress that really well?!”

Yes and no. Usually generic data compressors can’t. Most of them are very much oriented at finding repeated sequences of bytes. So if you have

a very smoothly varying surface height or image pixel color, e.g. a sequence of bytes 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, well that is not compressible

at all! There are no repeating byte sequences.

But, if you transform the sequence using some sort of “difference” between neighboring elements, then repeated byte sequences might start

appearing. At first I tried XOR’ing the neighboring elements together (interpreting each float as an uint32_t), since at some

point I saw that trick being mentioned in some “time series database” writeups

(e.g. Gorilla).

A completely unoptimized code to do that:

template<typename T>

static void EncodeDeltaXor(T* data, size_t dataElems)

{

T prev = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < dataElems; ++i)

{

T v = *data;

*data = v ^ prev;

prev = v;

++data;

}

}

template<typename T>

static void DecodeDeltaXor(T* data, size_t dataElems)

{

T prev = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < dataElems; ++i)

{

T v = *data;

v = prev ^ v;

*data = v;

prev = v;

++data;

}

}

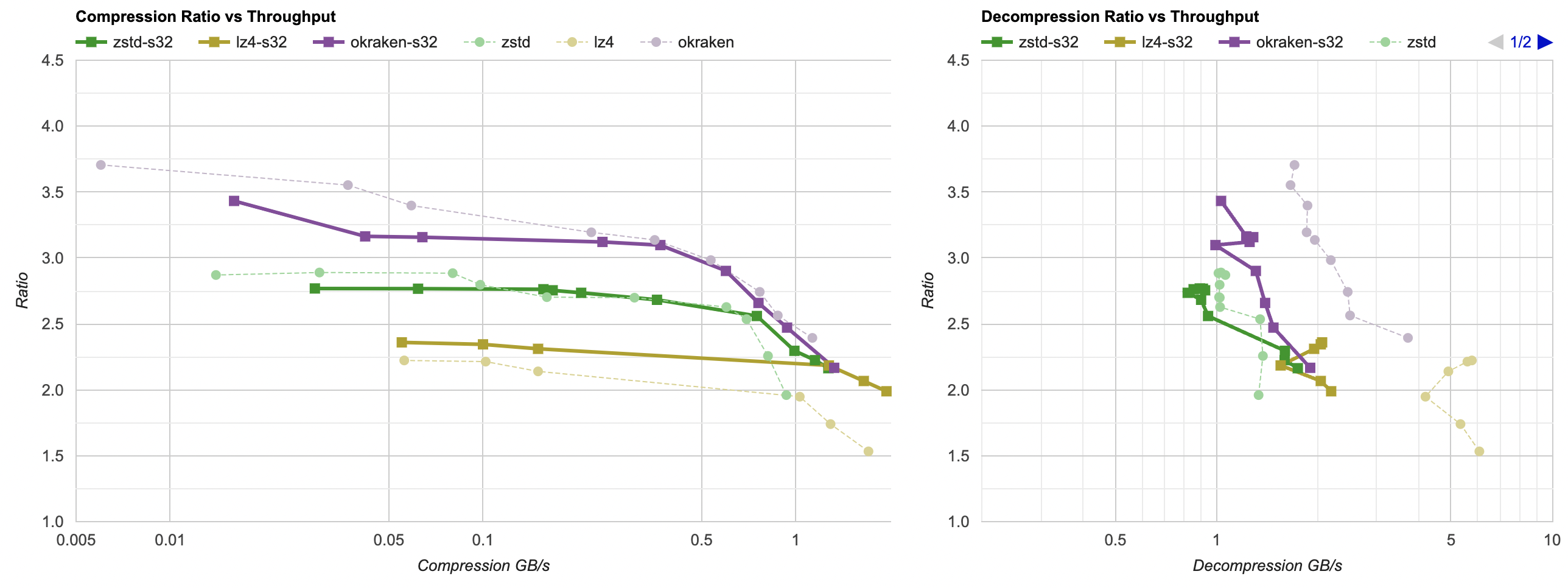

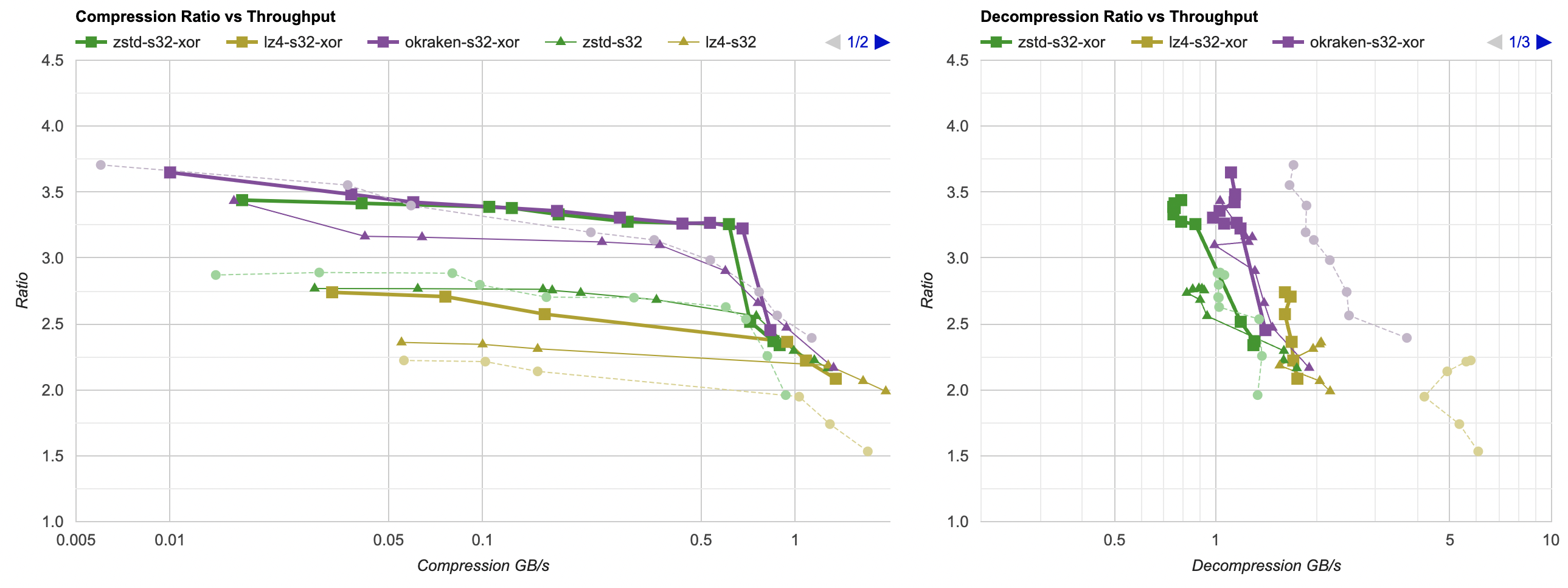

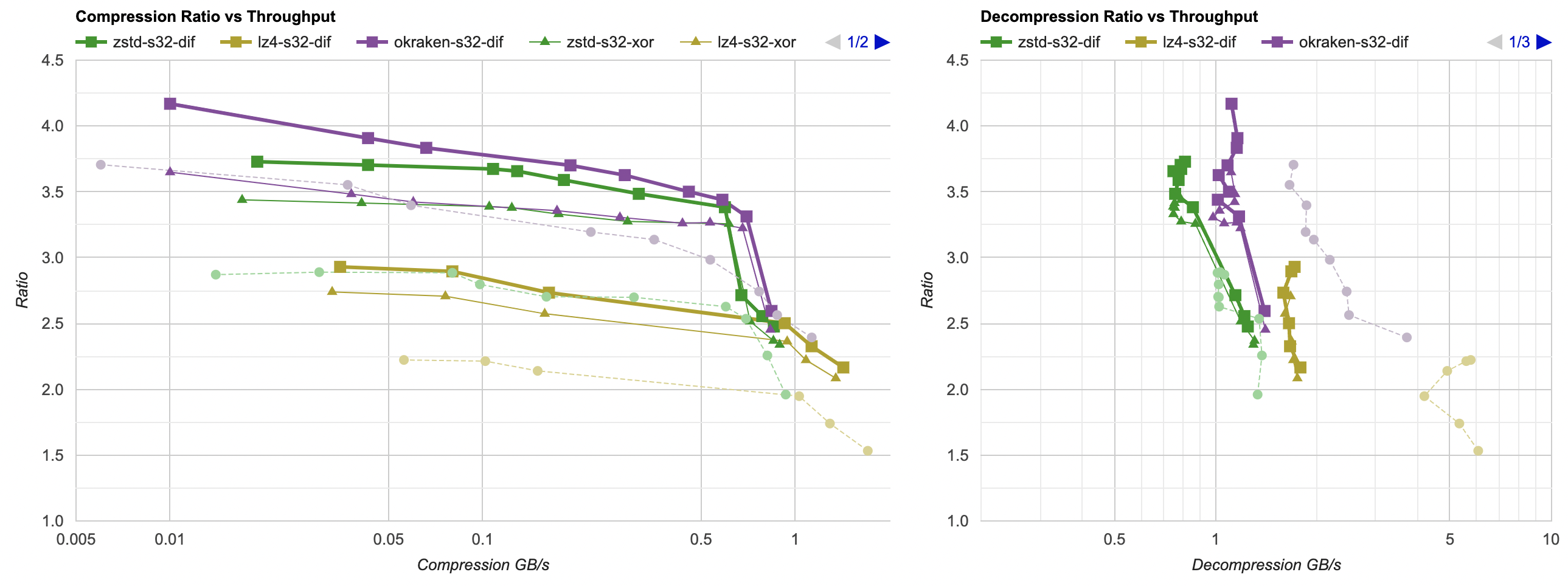

And that gives (faint dashed line: raw compression, thin line: previous attempt (split floats), thick line: split floats + XOR):

- Compression ratio is way better for zstd and lz4 (for kraken, only at lower levels).

- zstd pretty much reaches kraken compression levels! The lines almost overlap in the graph.

- Decompression speed takes a bit of a hit, as expected. I might need to do something about it later.

So far we got from 33.8MB (zstd) / 29.6MB (kraken) at beginning of the post down to 28MB (zstd, kraken), while still compressing in under 1 second. Nice, we’re getting somewhere.

Reorder floats + Delta

The “xor neighboring floats” trick from Gorilla database was in the context of then extracting the non-zero sequences of bits from the result and storing that

in less space than four bytes. I’m not doing any of that, so how about this: instead of XOR, do a difference (“delta”) between the neighboring elements?

Note that delta is done by reinterpreting data as if it were unsigned integers, i.e. these templates are called with uint32_t type (you can’t easily

do completely lossless floating point delta math).

template<typename T>

static void EncodeDeltaDif(T* data, size_t dataElems)

{

T prev = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < dataElems; ++i)

{

T v = *data;

*data = v - prev;

prev = v;

++data;

}

}

template<typename T>

static void DecodeDeltaDif(T* data, size_t dataElems)

{

T prev = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < dataElems; ++i)

{

T v = *data;

v = prev + v;

*data = v;

prev = v;

++data;

}

}

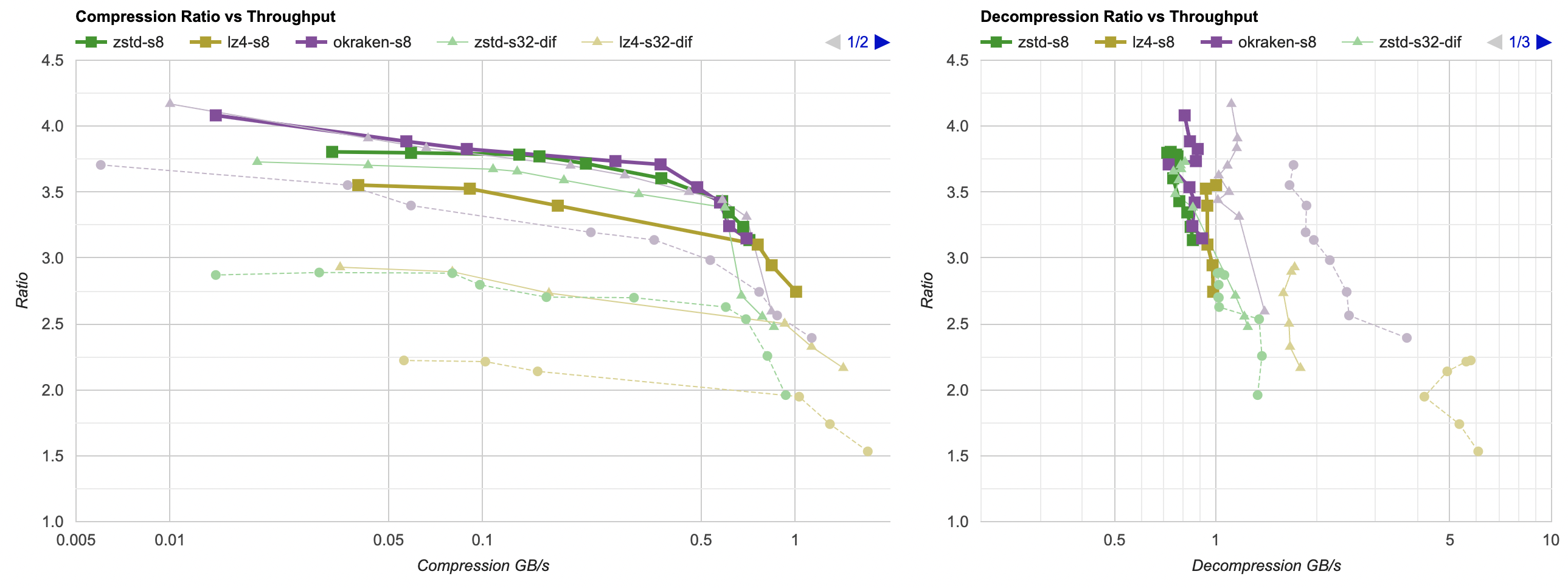

And that gives (faint dashed line: raw compression, thin line: previous attempt (split floats + XOR), thick line: split floats + delta):

Now that’s quite an improvement! All three compressors tested get their compression ratio lifted up. Good! Let’s keep on going.

Reorder bytes

Hey, how about instead of splitting each data point into 4-byte-wide “streams”, we split into 1-byte-wide ones? After all, general compression

libraries are oriented at finding byte sequences that would be repeating. This is also known as a “shuffle” filter elsewhere

(e.g. HDF5).

Exactly the same Split and UnSplit functions as above, just with uint8_t type.

Faint dashed line: raw compression, thin line: previous attempt (split floats + Delta), thick line: split bytes:

- kraken results are almost the same as with “split floats and delta”. Curious!

- zstd ratio (and compression speed) is improved a bit.

- lz4 ratio is improved a lot (it’s beating original unfiltered kraken at this point!).

I’ll declare this a small win, and let’s continue.

Reorder bytes + Delta

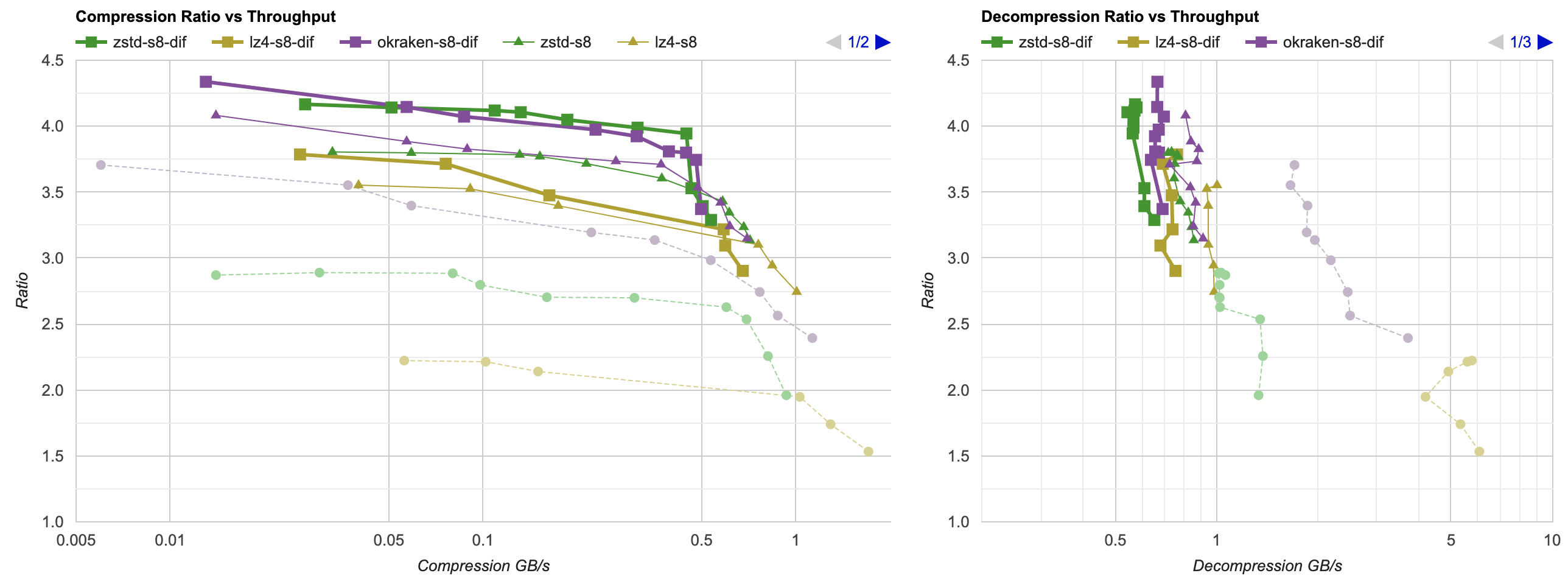

Split by bytes as previous, and delta-encode that. Faint dashed line: raw compression, thin line: previous attempt (split bytes), thick line: split bytes + delta:

Holy macaroni grated potato dumplings!

- Another compression ratio increase. Both zstd and kraken get our data to 23MB in about one second (whereas it was 33.8MB and 29.6MB at the start of the post).

- zstd actually slightly surpasses kraken at compression ratios in the area (“under 1 sec”) that I care about. 😮

- lz4 is not too shabby either, being well ahead of unfiltered kraken.

- Downside: decompression is slightly longer than 0.1 seconds now. Not “terrible”, but I’d want to look into whether all this reordering and delta could be sped up.

Conclusion and what’s next

There’s lots of other data filtering approaches and ideas I could have tried, but for now I’m gonna call “reorder bytes and delta” a pretty good win; it’s extremely simple to implement and gives a massive compression ratio improvement on my data set.

I did actually try a couple other filtering approaches. Split data by bits (using bitshuffle library) was producing worse ratios than splitting by bytes. Rotating each float left by one bit, to make the mantissa & exponent aligned on byte boundaties, was also not an impressive result. Oh well!

Maybe at some point I should also test filters specifically designed for 2D data (like the water and snow simulation data files in my test), e.g. something like PNG Paeth filter or JPEG-LS LOCO-I (aka “ClampedGrad”).

Next up, I’ll look at an open source library that does not advertise itself as a general data compressor, but I’m gonna try it anyway :) Until then!