Lossless Float Image Compression

Back in 2021 I looked at OpenEXR lossless compression options (and I think my findings led a change of the default zip compression level, as well as change of the compression library from zlib to libdeflate. Yay blogging about things!). Then in 2023 I looked at losslessly compressing a bunch of floating point data, some of which might be image-shaped.

Well, now a discussion somewhere else has nerd-sniped me to look into lossless compression of floating point images, and especially the ones that might have more than just RGB(A) color channels. Read on!

Four bullet point summary, if you’re in a hurry:

- Keep on using OpenEXR with ZIP compression.

- Soon OpenEXR might add HTJ2K compression; that compresses slightly better but is worse compression and decompression performance, so YMMV.

- JPEG-XL is not competitive with OpenEXR in this area today.

- You can cook up a “custom image compression” that seems to be better than all of EXR, EXR HTJ2K and JPEG-XL, while also being way faster.

My use case and the data set

What I wanted to primarily look at, are “multi-layer” images that would be used for film composition workflows. In such an image, a single pixel does not have just the typical RGB (and possibly alpha) channels, but might have more. Ambient occlusion, direct lighting, indirect lighting, depth, normal, velocity, object ID, material ID, and so on. And the data itself is almost always floating point values (either FP16 or FP32); sometimes with different precision for different channels within the same image.

There does not seem to be a readily available “standard image set” like that to test things on, so I grabbed some that I could find, and some I have rendered myself out of various Blender splash screen files. Here’s the 10 data files I’m testing on (total uncompressed pixel size: 3122MB):

| File | Resolution | Uncompressed size | Channels | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blender281rgb16.exr | 3840x2160 | 47.5MB | RGB half |  |

| Blender281rgb32.exr | 3840x2160 | 94.9MB | RGB float | |

| Blender281layered16.exr | 3840x2160 | 332.2MB | 21 channels, half |    |

| Blender281layered32.exr | 3840x2160 | 664.5MB | 21 channels, float | |

| Blender35.exr | 3840x2160 | 332.2MB | 18 channels, mixed half/float |    |

| Blender40.exr | 3840x2160 | 348.0MB | 15 channels, mixed half/float |    |

| Blender41.exr | 3840x2160 | 743.6MB | 37 channels, mixed half/float |     |

| Blender43.exr | 3840x2160 | 47.5MB | RGB half |  |

| ph_brown_photostudio_02_8k.exr | 8192x4096 | 384.0MB | RGB float, from polyhaven |  |

| ph_golden_gate_hills_4k.exr | 4096x2048 | 128.0MB | RGBA float, from polyhaven |  |

OpenEXR

OpenEXR is an image file format that has existed since 1999, and is primarily used within film, vfx and game industries. It has several lossless compression modes (see my previous blog post series).

It looks like OpenEXR 3.4 (should be out 2025 Q3) is adding a new HTJ2K compression mode, which is based on

“High-Throughput JPEG 2000” format/algorithms, using open source

OpenJPH library. The new mode is already in OpenEXR main branch

(PR #2041).

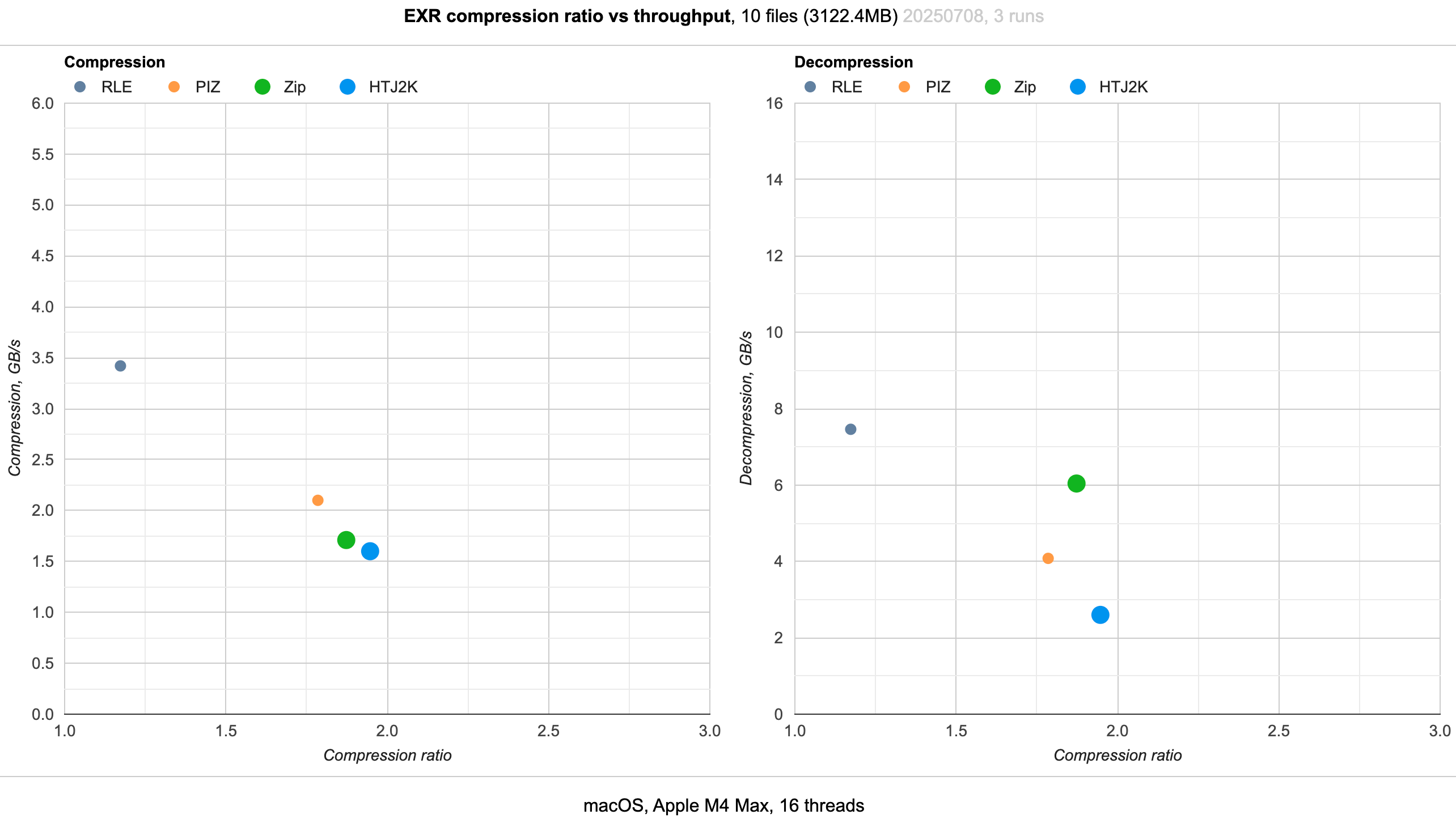

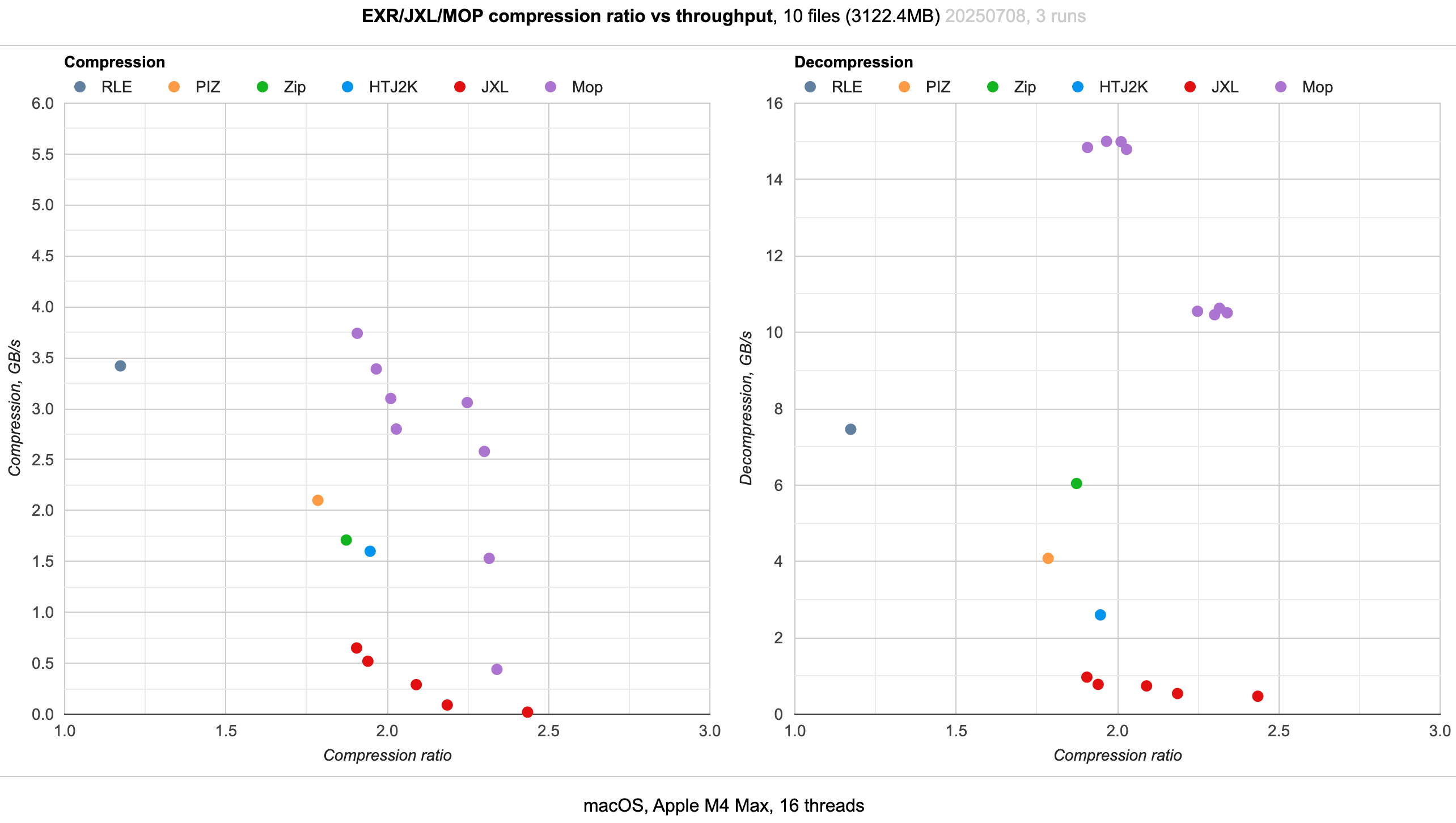

So here’s how EXR does on my data set (click for a larger interactive chart):

This is two plots: compression ratio vs. compression performance, and compression ratio vs. decompression performance. In both cases, the best place on the chart is top right – the largest compression ratio, and the best performance.

For performance, I’m measuring it in GB/s, in terms of uncompressed data size. That is, if we have 1GB worth of raw image pixel data and processing it took half a second, that’s 2GB/s throughput (even if compressed data size might be different). Note that the vertical scale of both graphs is different. I am measuring compression/decompression time without actual disk I/O, for simplicity – that is, I am “writing” and “reading” “files” from memory. The graph is from a run on Apple MacBookPro M4 Max, with things being compiled in “Release” build configuration using Xcode/clang 16.1.

Green dot is EXR ZIP at default compression level (which is 4, but changing the level does not affect things much). Blue dot is the new EXR HTJ2K compression – a bit better compression ratio, but also lower performance. Hmm dunno, not very impressive? However:

- From what I understand, HTJ2K achieves better ratio on RGB images by applying a de-correlation transform. In case of multi-layer EXR files (which is most of my data set), it only does that for one layer (usually the “final color” one), but does not try to do that on, for example, “direct diffuse” layer which is also “actually RGB colors”. Maybe future work within OpenEXR HTJ2K will improve this?

- Initial HTJ2K evaluation done in 2024 found that a commercial HTJ2K implementation (from Kakadu) is quite a bit faster than the OpenJPH that is used in OpenEXR. Maybe future work within OpenJPH will speed it up?

- It very well might be that once/if OpenEXR will get lossy HTJ2K, things would be much more interesting. But that is a whole another topic.

I was testing OpenEXR main branch code from 2025 June (3.4.0-dev, rev 45ee12752), and things are multi-threaded via

Imf::setGlobalThreadCount(). Addition of HTJ2K compression codec adds 308 kilobytes to executable size by the way (on Windows x64 build).

Moving on.

JPEG-XL lossless

JPEG-XL is a modern image file format that aims to be a good improvement over many already existing image formats; both lossless and lossy, supporting stardard and high dynamic range images, and so on. There’s a recent “The JPEG XL Image Coding System” paper on arXiv with many details and impressive results, and the reference open source implementation is libjxl.

However, the arXiv paper above does not have any comparisons in how well JPEG-XL does on floating point data (it does have HDR image comparisons, but at 10/12/16 bit integers with a HDR transfer function, which is not the same). So here is me, trying out JPEG-XL lossless mode on images that are either FP16 or FP32 data, often with many layers (JPEG-XL supports this via “additional channels” concept), and sometimes with different floating point types based on channel.

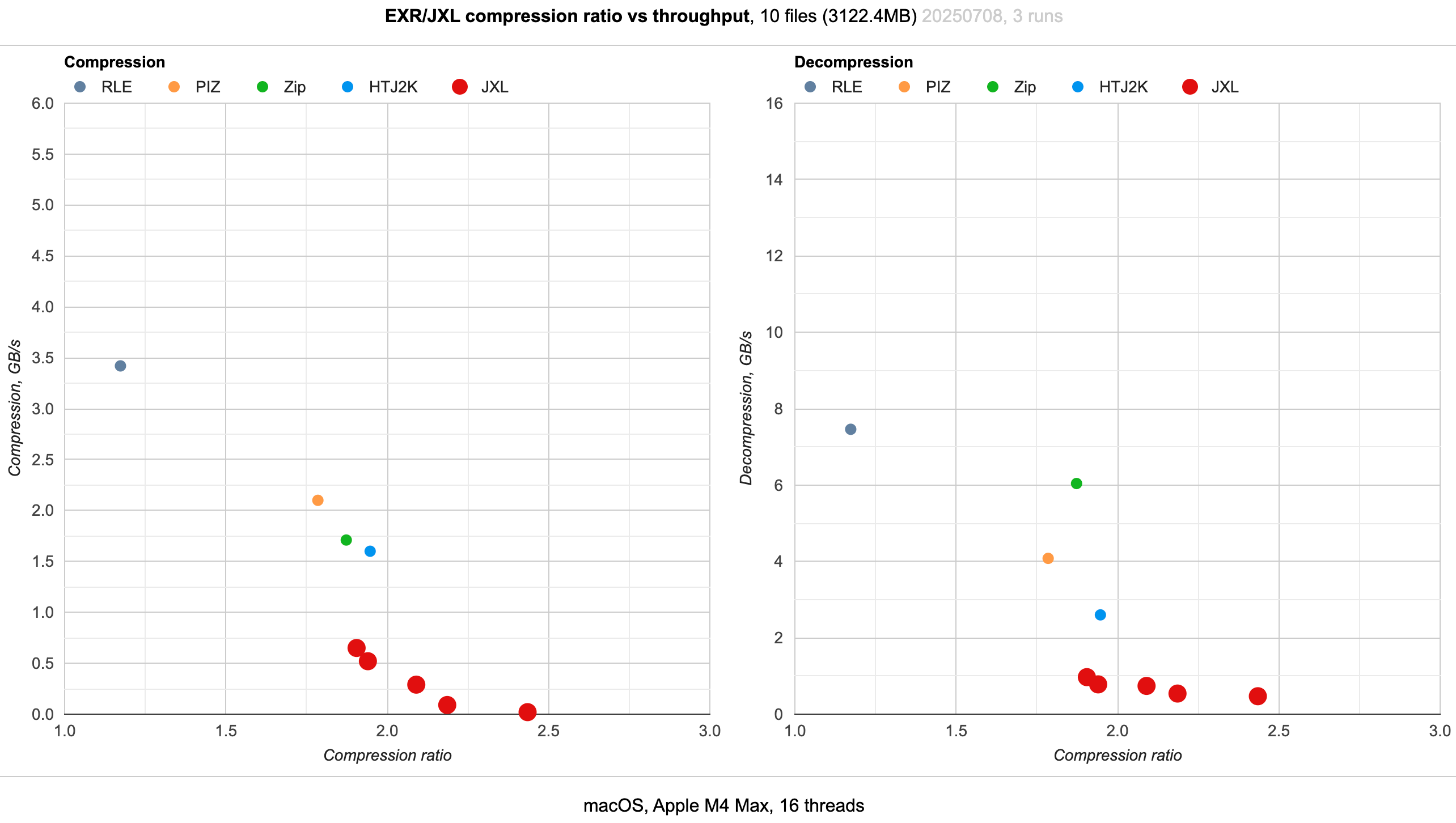

Here’s results with existing EXR data, and JPEG-XL additions in larger red dots (click for an interactive chart):

Immediate thoughts are okay this can achieve better compression, coupled with geez that is slow. Expanding a bit:

- At compression effort 1-3 JPEG-XL does not win against OpenEXR (ZIP / HTJ2K) on compression ration, while being 3x slower to compress, and 3x-7x slower to decompress. So that is clearly not a useful place to be.

- At compression effort levels 4+ it starts winning in compression ratio. Level 4 wins against HTJ2K a bit (1.947x -> 2.09x); the default level 7 wins more (2.186x), and there’s quite a large increase in ratio at level 8 (2.435x). I briefly tried levels 9 and 10, but they do not seem to be giving much ratio gains, while being extraordinarily slow to compress. Even level 8 is already 100 times slower to compress than EXR, and 5-13x slower to decompress. So yeah, if final file size is really important to you, then maybe; on the other hand, 100x slower compression is, well, slow.

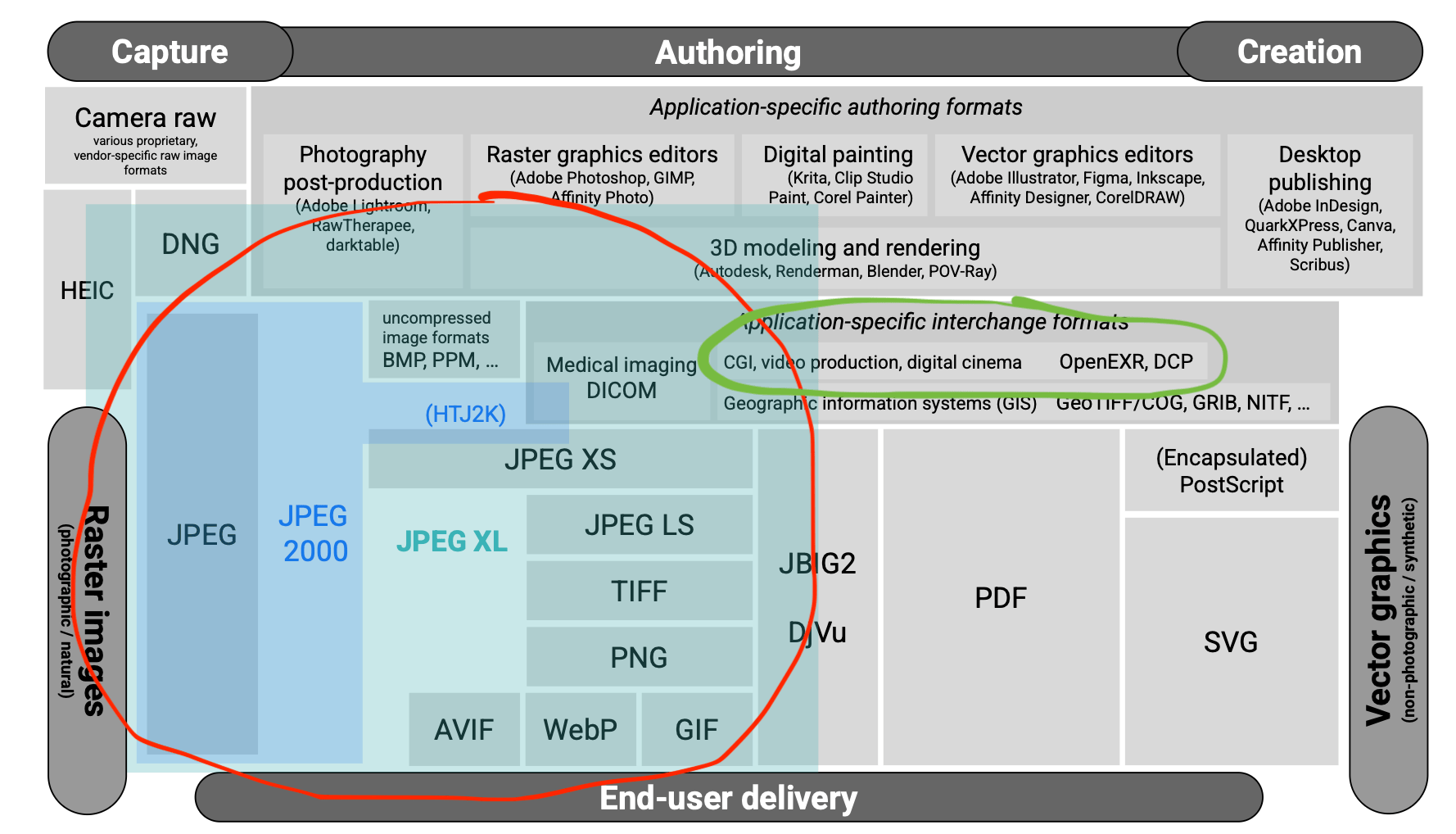

Looking at the feature set and documentation of the format, it feels that JPEG-XL is mostly and primarily is targeted at “actually displayed images,

perhaps for the web”. Whereas with EXR, you can immediately see that it is not meant for “images that are displayed” – it does not even

have a concept of low dynamic range imagery; everything is geared towards it being for images used in the middle of the pipeline. From that falls out

built-in features like arbitrary number of channels, multi-part images, mipmaps, etc. Within JPEG-XL, everything is centered around “color”,

and while it can do more than just color, these feel like bolted-on things. It can do multiple frames, but these have to be same size/format

and are meant in the “animation frames” sense; it can do multiple layers but these are meant in the “photoshop layers” sense; it talks about

storing floating point data, but it is in the “HDR color or values a bit out of color gamut” sense. And that is fine; the JPEG-XL coding system

paper itself has a chart of what JPEG-XL wants to be (I circled that with red) and where EXR is (circled with green):

More subjective notes and impressions:

- Perhaps the floating point paths within

libjxldid not (yet?) get the same attention as “regular images” did; it is very possible that they will improve the performance and/or ratio in the future (I was testing end-of-June 2025 code). - A cumbersome part of

libjxlis that color channels need to be interleaved, and all the “other channels” need to be separate (planar). All my data is fully interleaved, so it costs some performance to arrange it as libjxl wants, both for compression and after decompression. As a user, it would be much more convenient to use if their API was similar to OpenEXRSlicethat takes a pointer and two strides (stride between pixels, and stride between rows). Then any combination of interleaved/planar or mixed formats for different channels could be passed with the same API. In my own test code, reading and writing EXR images using OpenEXR is 80 lines of code, whereas JPEG-XL via libjxl is 550 lines. - On half-precision floats (FP16),

libjxlcurrently is not fully lossless – subnormal values do not roundtrip correctly (issue #3881). The documentation also says that non-finite values (infinities / NaNs) in both FP32 and FP16 are not expected to roundtrip in an otherwise lossless mode. This is in contrast with EXR, where even for NaNs, their exact bit patterns are fully preserved. Again, this does not matter if the intended use case is “images on screen”, but matters if your use case is “this looks like an image, but is just some data”. - From what I can tell, some people did performance evaluations of EXR ZIP vs JPEG-XL by using

ffmpegEXR support; do not do that. At least right now, ffmpeg EXR code is their own custom implementation, that is completely single threaded and lacks some other optimizations that official OpenEXR library does.

I was testing libjxl main branch code from 2025 June (0.12-dev, rev a75b322e), and things are multi-threaded via

JxlThreadParallelRunner. Library adds 6017 kilobytes to executable size (on Windows x64 build).

And now for something completely different:

Mesh Optimizer to compress images, why not?

Back when I was playing around with floating point data compression, one of the things I tried was using meshoptimizer by Arseny Kapoulkine to losslessly compress the data. It worked quite well, so why not try this again. Especially since it got both compression ratio and performance improvements since then.

So let’s try a “MOP”, which is not an actual image format, just something I quickly cooked up:

- A small header with image size and channel information,

- Then image is split into chunks, each being 16K pixels in size. Each chunk is compressed independently and in parallel.

- A small table with compressed sizes for each chunk is written after the header, followed by the compressed data itself for each chunk.

- Mesh optimizer needs “vertex size” (pixel size in this case) to be multiple of four; if that is not the case the chunk data is padded with zeroes inside the compression/decompression code.

- And just like the previous time: mesh optimizer vertex codec is not an LZ-based compressor (it seems to be more like delta/prediction scheme that is packed nicely), and you can further compress the result by just piping it to a regular lossless compressor. In my case, I used zstd.

So here’s how “MOP” does on my data set (click for a larger interactive chart):

The purple dots are the new “MOP” additions. You can see there are two groups of them: 1) around 2.0x ratio and very high decompression speed is just mesh optimizer vertex codec, 2) around 2.3x ratio and slightly lower decompression speed is mesh optimizer codec followed by zstd.

And that is… very impressive, I think:

- Just mesh optimizer vertex codec itself is about the same or slightly higher compression ratio as EXR HTJ2K, while being almost 2x faster to compress and 5x faster to decompress.

- Coupled with zstd, it achieves compression ratio that is between JPEG-XL levels 7-8 (2.3x), while being 30-100 times faster to compress and 20 times faster to decompress. This combination also very handily wins against EXR (both ZIP and HTJ2K), in both ratio and performance.

- Arseny is a witch!?

I was testing mesh optimizer v0.24 (2025 June) and zstd v1.5.7 (2025 Feb). Mesh optimizer itself adds just 26 kilobytes (!) of executable code; however zstd adds 405 kilobytes.

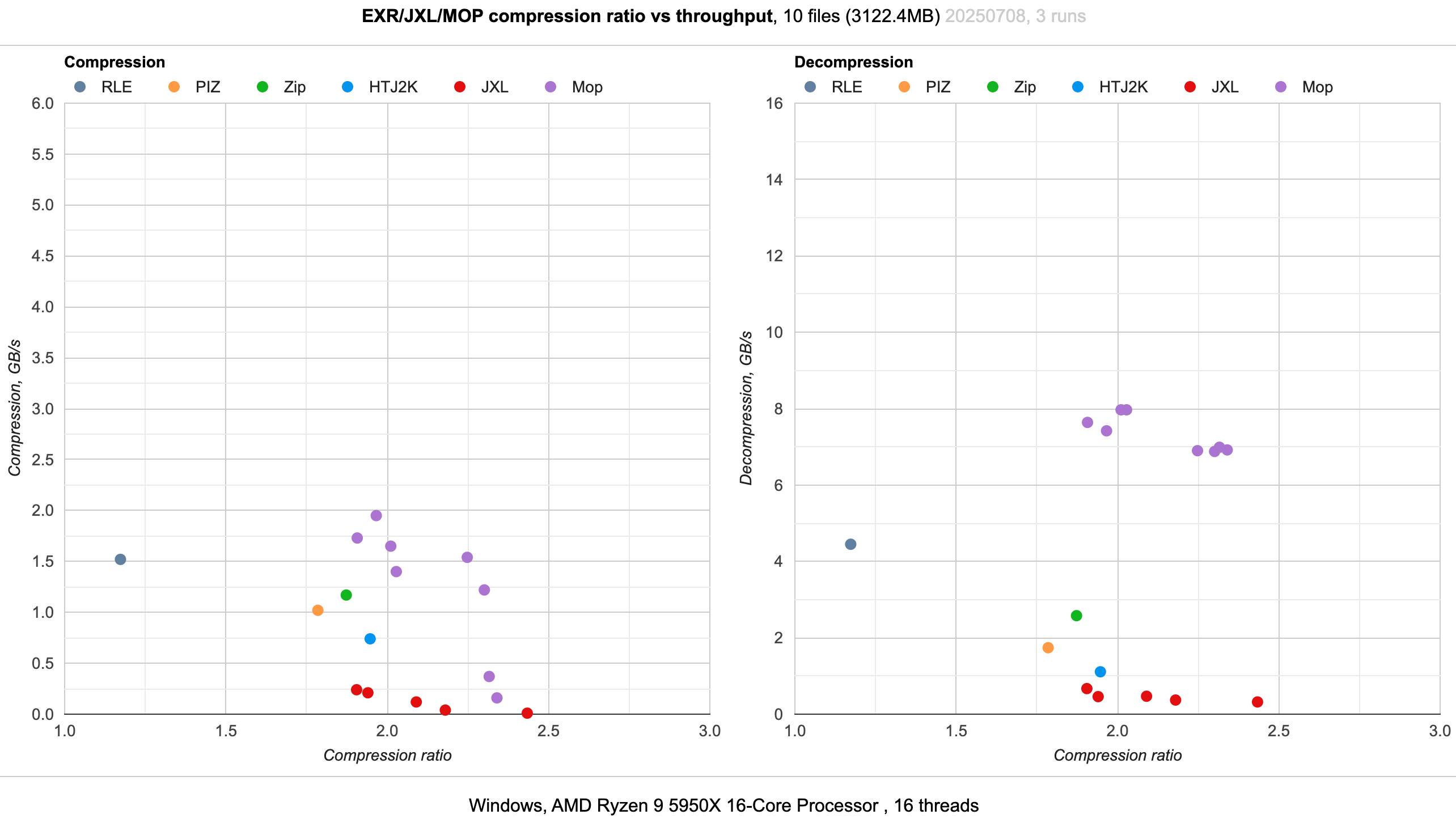

And here are the results of all the above, running on a different CPU, OS and compiler (Ryzen 5950X, Windows 10, Visual Studio 2022 v17.14).

Everything is several times slower (some of that is due to Apple M4 having crazy high memory bandwidth, some of that CPU differences, some of that

compiler differences, some OS behavior with large allocations, etc.). But overall “shape” of the charts is more or less the same:

That’s it for now!

So there. Source code of everything above is over at github.com/aras-p/test_exr_htj2k_jxl. Again, my own take aways are:

- EXR ZIP is fine,

- EXR HTJ2K is slightly better compression, worse performance. There is hope that performance can be improved.

- JPEG-XL does not feel like a natural fit for this (multi-layered, floating point) images right now. However, it could become one in the future, perhaps.

- JPEG-XL (libjxl) compression performance is very slow, however it can achieve better ratios than EXR. Decompression performance is also several times slower. It is possible that both performance and ratio could be improved, especially if they did not focus on floating point cases yet.

- Mesh Optimizer (optionally coupled with zstd) is very impressive, both in terms of compression ratio and performance. It is not an actual image format that exists today, but if you need to losslessly compress some floating point images for internal needs only, it is worth looking at.

And again, all of that was for fully lossless compression. Lossy compression is a whole another topic, that I may or might not look into someday. Or, someone else could look! Feel free to use the image set I have used.