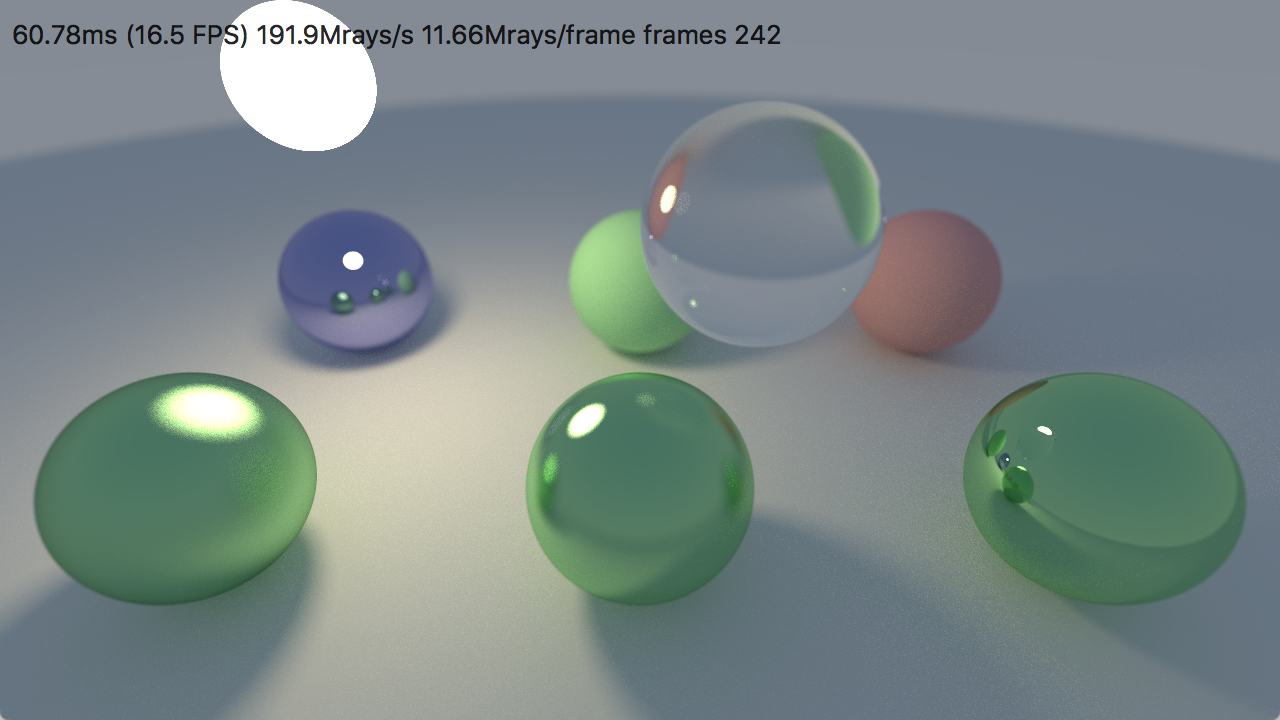

Daily Pathtracer Part 7: Initial SIMD

Introduction and index of this series is here.

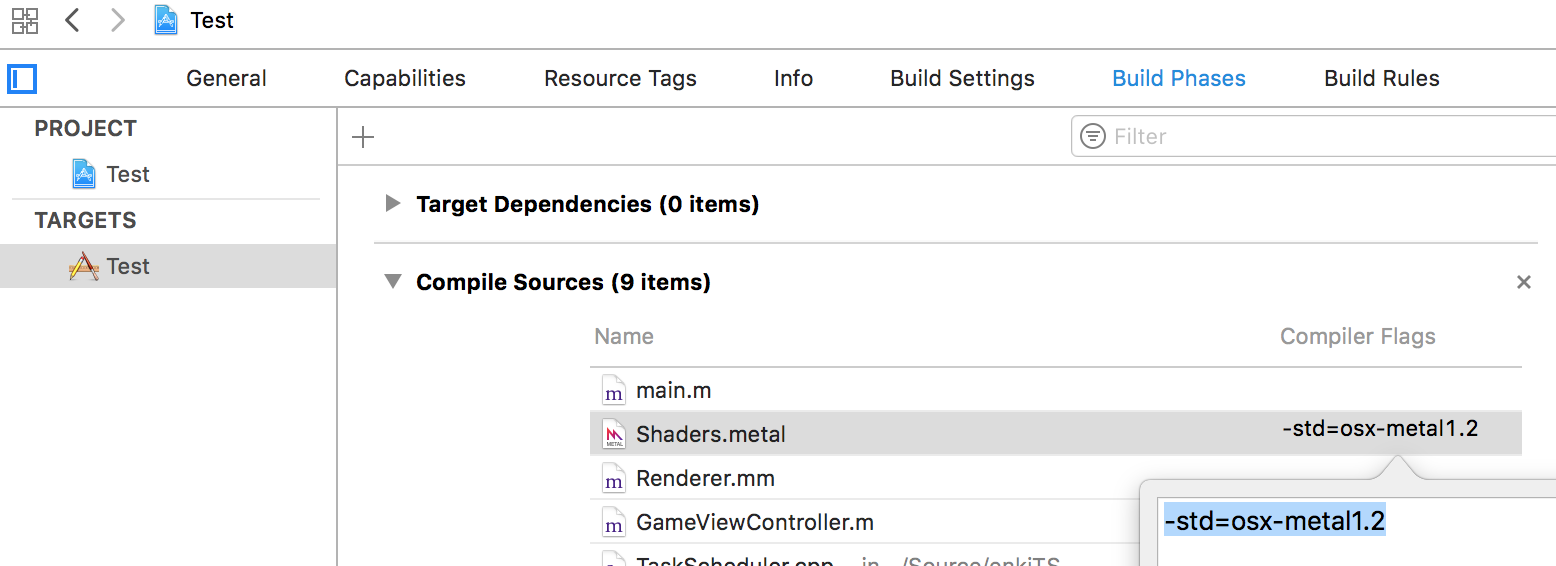

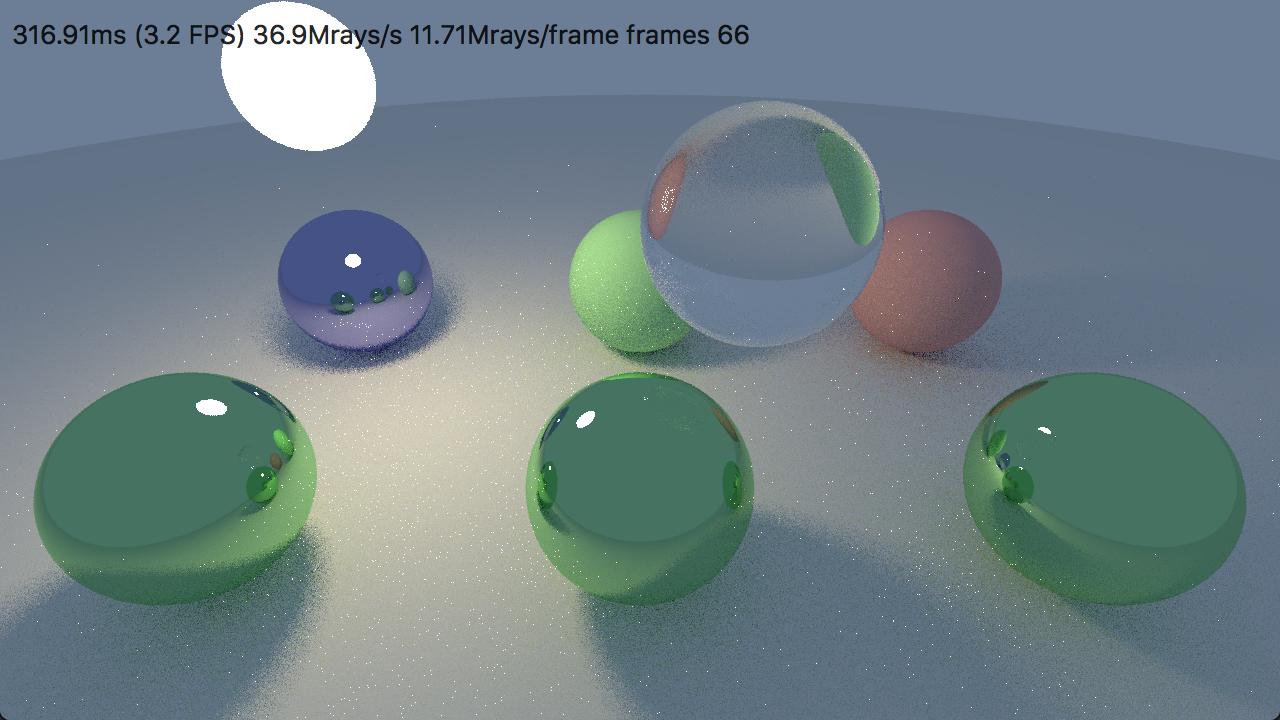

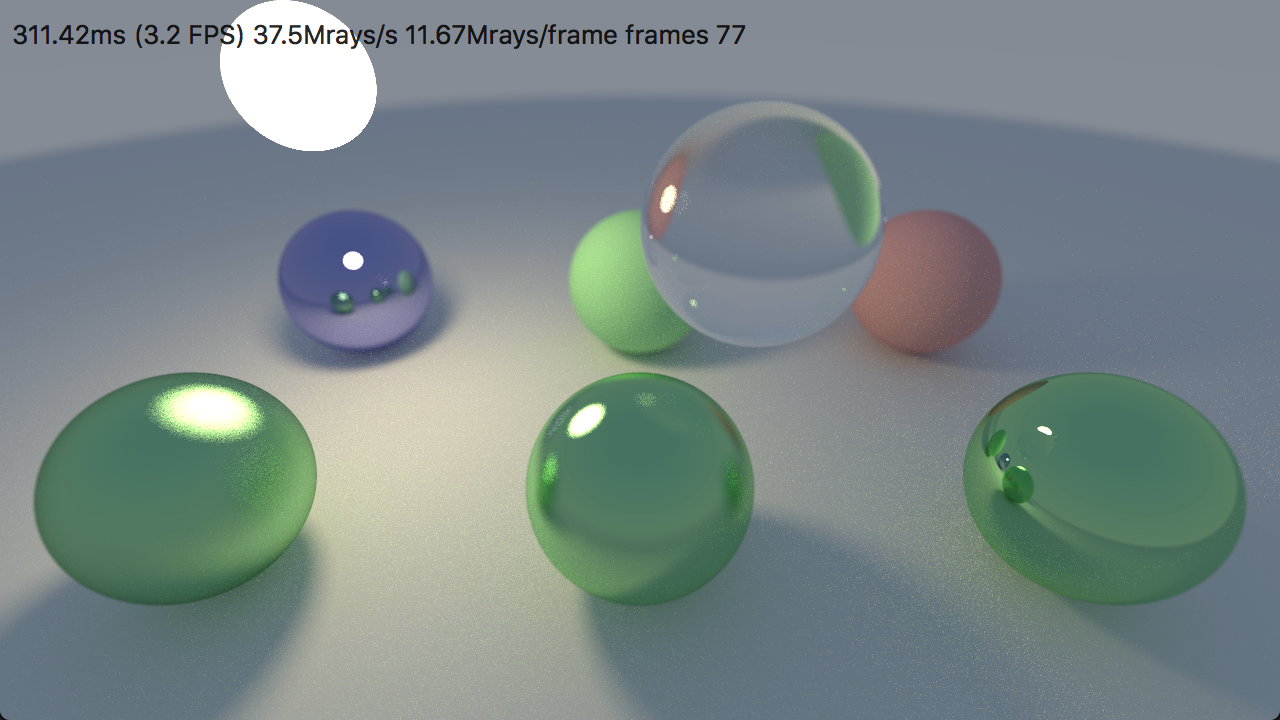

Let’s get back to the CPU C++ implementation. I want to try SIMD and similar stuffs now!

Warning: I don’t have much (any?) actual experience with SIMD programming. I know conceptually what it is, have written a tiny bit of SIMD assembly/intrinsics code in my life, but nothing that I could say I “know” or even “have a clue” about it. So whatever I do next, might be completely stupid! This is a learning exercise for me too! You’ve been warned.

SIMD, what’s that?

SIMD is for “Single instruction, multiple data”, and the first sentence about it on Wikipedia says “a class of parallel computers in Flynn’s taxonomy” which is, errr, not that useful as an introduction :) Basically SIMD can be viewed as CPU instructions that do “operation” on a bunch of “items” at once. For example, “take these 4 numbers, add these other 4 numbers to them, and get a 4-number result”.

Different CPUs have had a whole bunch of different SIMD instruction sets over the years, and the most common today are:

- SSE for x86 (Intel/AMD) CPUs.

- SSE2 can be pretty much assumed to be “everywhere”; it’s been in Intel CPUs since 2001 and AMD CPUs since 2003.

- There are later SSE versions (SSE3, SSE4 etc.), and then later on there’s AVX too.

- NEON for ARM (“almost everything mobile”) CPUs.

It’s often said that “graphics” or “multimedia” is an area where SIMD is extremely beneficial, so let’s see how or if that applies to our toy path tracer.

Baby’s first SIMD: SSE for the vector class

The first thing that almost everyone immediately notices is “hey, I have this 3D vector class, let’s make

that use SIMD”. This seems to also be taught as “that’s what SIMD is for” at many universities.

In our case, we have a float3 struct

with three numbers in it, and a bunch of operations (addition, multiplication etc.) do the same thing on

all of them.

Spoiler alert: this isn’t a very good approach. I know that, but I also meet quite many people who don’t, for some reason. See for example this old post “The Ubiquitous SSE vector class: Debunking a common myth” by Fabian Giesen.

Let’s make that use SSE instructions. A standard way to use them in C++ is via

“intrinsic instructions”,

that basically have a data type of __m128 (4 single precision floats, total 128 bits) and instructions like

_mm_add_ps and so on. It’s “a bit” unreadable, if you ask me… But the good news is, these data types

and functions work on pretty much all compilers (e.g. MSVC, clang and gcc) so that covers your cross-platform

needs, as long as it’s Intel/AMD CPUs you’re targeting.

I turned my float3 to use SSE very similar to how it’s described in How To Write A Maths Library In 2016 by Richard Mitton. Here’s the commit.

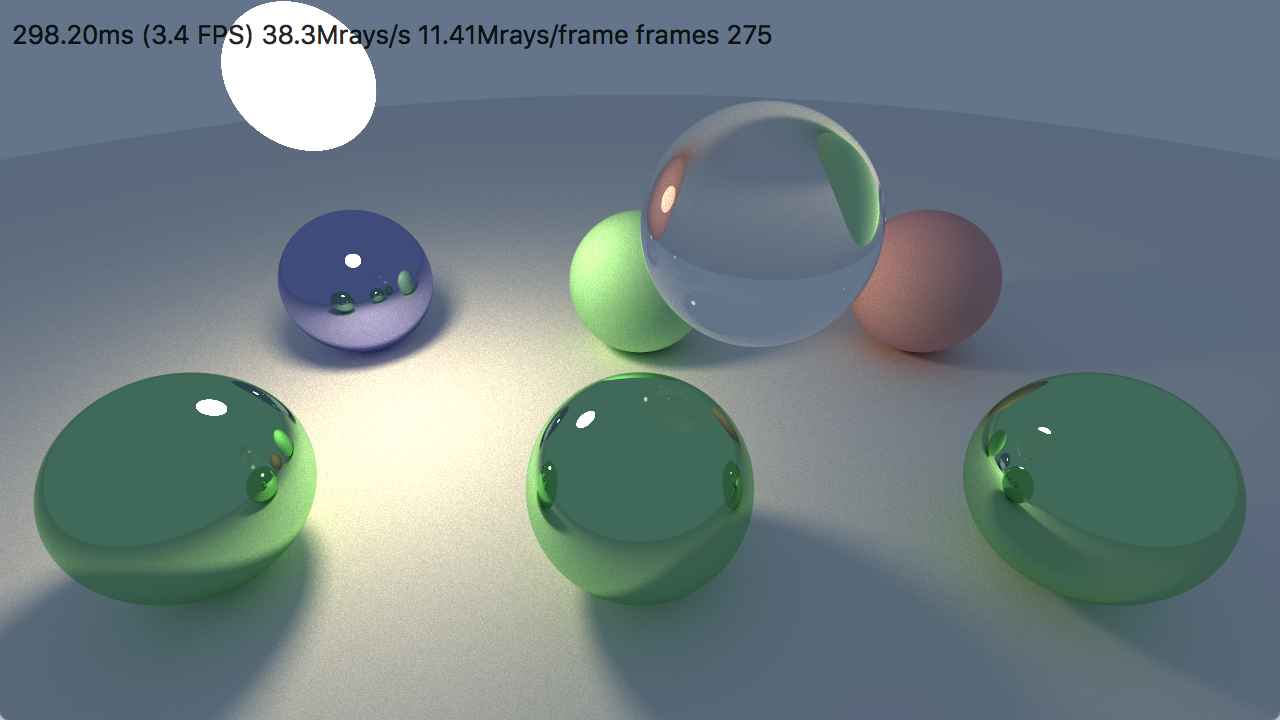

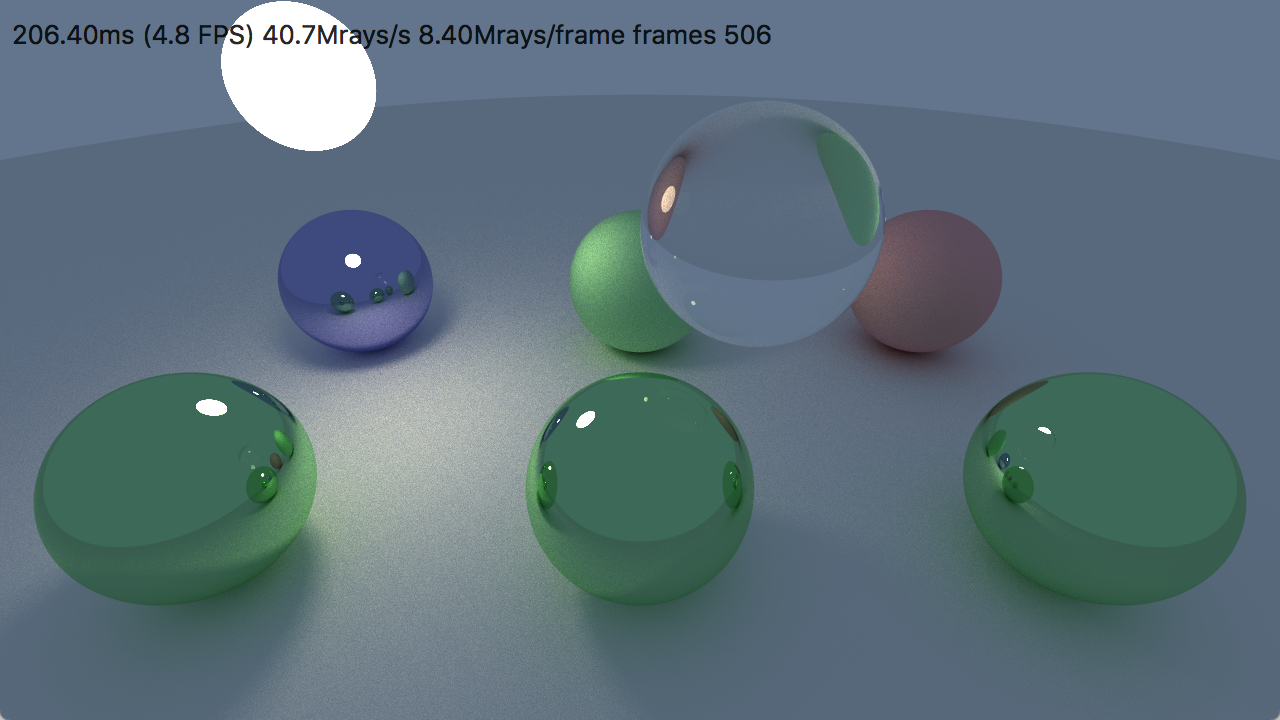

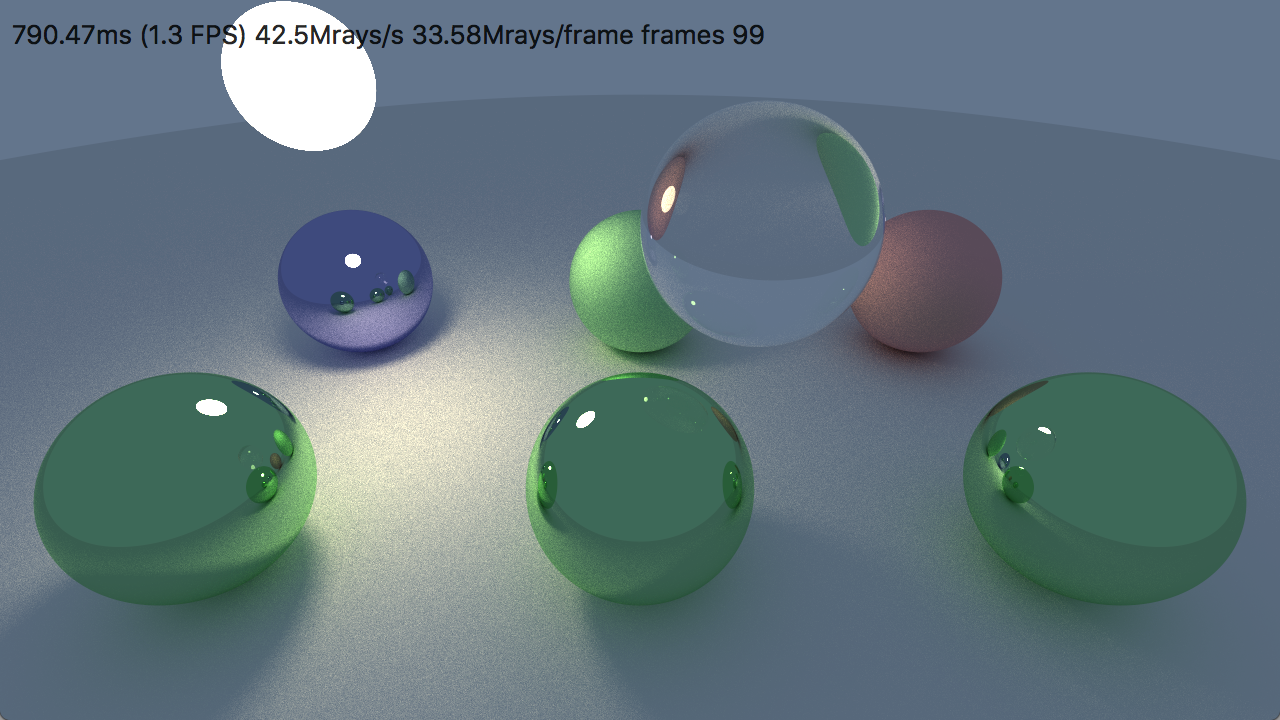

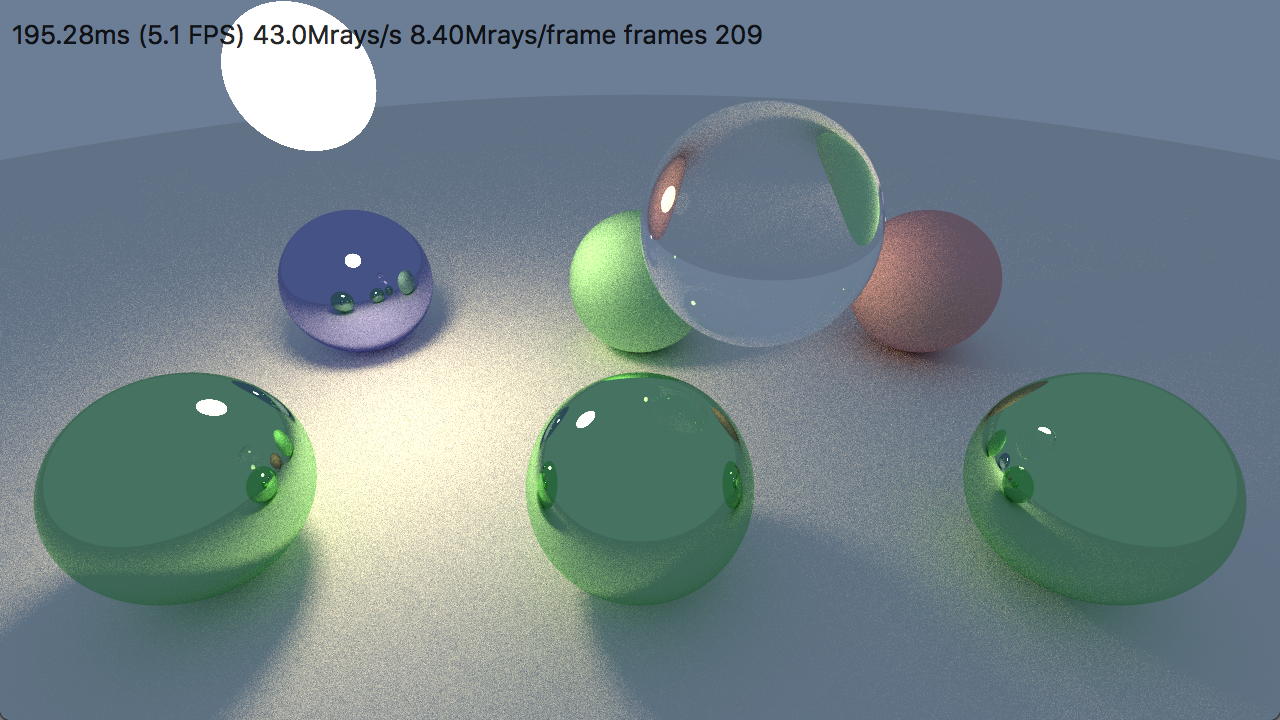

- PC (AMD ThreadRipper, 16 threads): 135 -> 134 Mray/s.

- Mac (MacBookPro, 8 threads): 38.7 -> 44.2 Mray/s.

Huh, that’s a bit underwhelming, isn’t it? Performance on PC (MSVC compiler) pretty much the same. Performance on Mac quite a bit better, but nowhere near “yeah 4x faster!” levels :)

This does make sense though. The float3 struct is explicitly using SIMD now, however a whole lot of remaining

code still stays “scalar” (i.e. using regular float variables). For example, one of the “heavy” functions,

where a lot of time is spent, is HitSphere, and it has a lot of floats

and branches in it:

bool HitSphere(const Ray& r, const Sphere& s, float tMin, float tMax, Hit& outHit)

{

float3 oc = r.orig - s.center; // SIMD

float b = dot(oc, r.dir); // scalar

float c = dot(oc, oc) - s.radius*s.radius; // scalar

float discr = b*b - c; // scalar

if (discr > 0) // branch

{

float discrSq = sqrtf(discr); // scalar

float t = (-b - discrSq); // scalar

if (t < tMax && t > tMin) // branch

{

outHit.pos = r.pointAt(t); // SIMD

outHit.normal = (outHit.pos - s.center) * s.invRadius; // SIMD

outHit.t = t;

return true;

}

t = (-b + discrSq); // scalar

if (t < tMax && t > tMin) // branch

{

outHit.pos = r.pointAt(t); // SIMD

outHit.normal = (outHit.pos - s.center) * s.invRadius; // SIMD

outHit.t = t;

return true;

}

}

return false;

}

I’ve also enabled __vectorcall

on MSVC and changed some functions to take float3 by value instead of by const-reference

(see commit),

but it did not change things noticeably in this case.

I’ve heard of “fast math” compiler setting

As a topic jump, let’s try telling the compiler “you know what, you can pretend that floating point nubers obey simple algebra rules”.

What? Yeah that’s right, floating point numbers as typically represented in computers (e.g.

floatdouble) have a lot of interesting properties. For example,a + (b + c)isn’t necessarily the same as(a + b) + cwith floats. You can read a whole lot about them at Bruce Dawson’s blog posts.

C++ compilers have options to say “you know what, relax with floats a bit; I’m fine with potentially not-exact

optimizations to calculations”. In MSVC that’s /fp:fast flag;

whereas on clang/gcc it’s -ffast-math flag.

Let’s switch

them on:

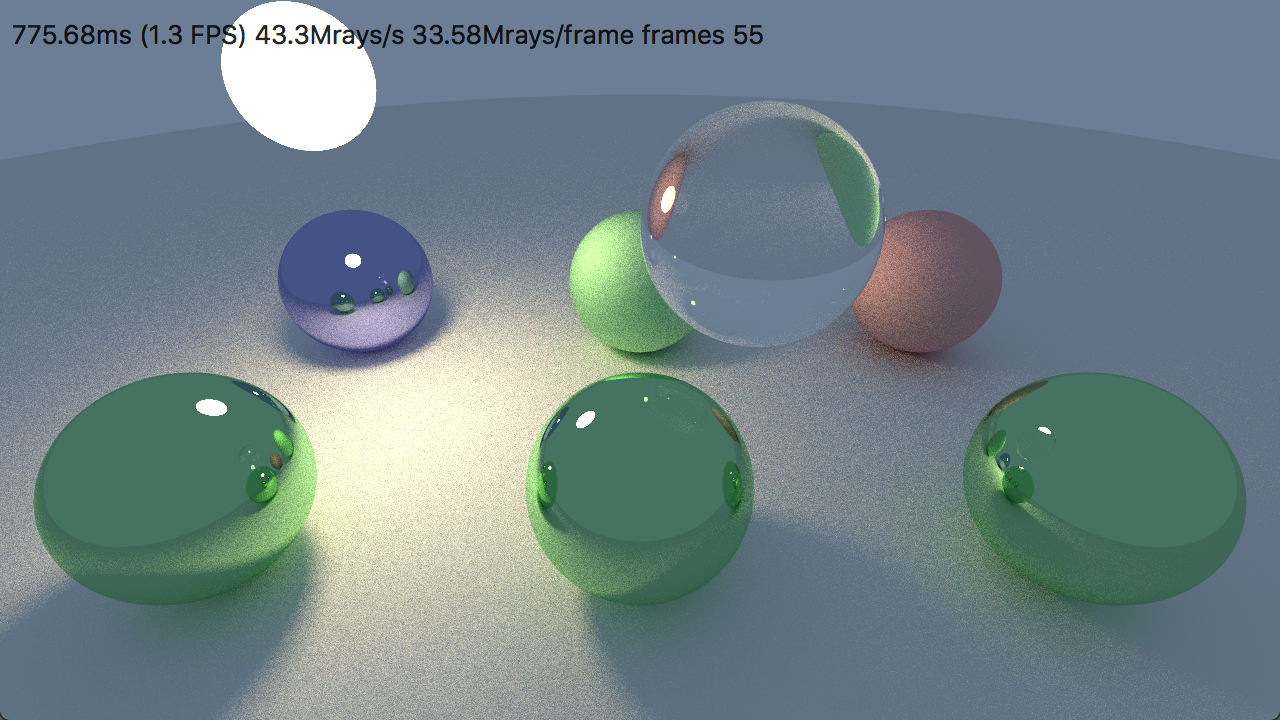

- PC: 134 -> 171 Mray/s.

- Mac: 44.2 -> 42.6 Mray/s.

It didn’t do anything on Mac (clang compiler), in fact made it a tiny bit slower… but whoa, look at that Windows (MSVC compiler) speedup! ⊙.☉

What’s a proper way to do SIMD?

Let’s get back to SIMD. The way I did float3 with SSE has some downsides, with major ones being:

- It does not lead to all operations using SIMD, for example doing dot products (of which there are plenty in graphics) ends up doing a bunch of scalar code. Yes, that quite likely could be improved somehow, but still, outside of regular “add/multiply individual vector components”, other operations do not easily map to SIMD.

- SSE works on 4 floats at a time, but our

float3only uses three. This leaves one “SIMD lane” not doing any useful work. If I were to use AVX SIMD instructions – these work on 8 floats at a time – that would get even less efficient.

I think it’s general knowledge that “a more proper” approach to SIMD (or optimization in general) is changing the mindset, by essentially going from “one thing at a time” to “many things at a time”.

Aside: in shader programming, you might think that basic HLSL types like

float3orfloat4map to “SIMD” type of processing, but that’s not the case on modern GPUs. It was true 10-15 years ago, but since then the GPUs moved to be so-called “scalar” architectures. Everyfloat3in shader code just turns into three floats. But the key thing is: the GPU is not executing one shader at a time; it runs a whole bunch of them (on separate pixels/vertices/…)! So each and everyfloatis “in fact” something like afloat64, with every “lane” being part of a different pixel. “Running Code at a Teraflop: How a GPU Shader Core Works” by Kayvon Fatahalian is a great introduction to this.

Mike Acton has a lot of material on “changing mindset for optimization”, e.g. this slides-as-post-it-notes gallery,

or the CppCon 2014 talk. In our case, we have a lot of

“one thing at a time”: one ray vs one sphere intersection check; generating one random value; and so on.

Mike Acton has a lot of material on “changing mindset for optimization”, e.g. this slides-as-post-it-notes gallery,

or the CppCon 2014 talk. In our case, we have a lot of

“one thing at a time”: one ray vs one sphere intersection check; generating one random value; and so on.

There are at least several ways how to make current code more SIMD-friendly:

- Work on more rays at once. I think this is called “packet ray tracing”. 4 rays at once would map nicely to SSE, 8 rays at once to AVX, and so on.

- Still work on one ray at a time, but at least change

HitWorld/HitSpherefunctions to check more than one sphere at a time. This one’s easier to do right now, so let’s try that :)

Right now code to do “ray vs world” check looks like this:

HitWorld(...)

{

for (all spheres)

{

if (ray hits sphere closer)

{

remember it;

}

}

return closest;

}

conceptually, it could be changed to this, with N probably being 4 for SSE:

HitWorld(...)

{

for (chunk-of-N-spheres from all spheres)

{

if (ray hits chunk-of-N-spheres closer)

{

remember it;

}

}

return closest;

}

I’ve heard of “Structure of Arrays”, what’s that?

Before diving into doing that, let’s rearrange our data a bit. Very much like aside on the GPUs above, we probably want to split our data into “separate components”, so that instead of all spheres being an “array of structures” (AoS) style:

struct Sphere { float3 center; float radius; };

Sphere spheres[];

it would instead be a “structure of arrays” (SoA) style:

struct Spheres

{

float centerX[];

float centerY[];

float centerZ[];

float radius[];

};

this way, whenever “test ray against N spheres” code needs to fetch, say, radius of N spheres, it can just load N consecutive numbers from memory.

Let’s do just that, without doing actual SIMD for the ray-vs-spheres checking yet. Instead of a

bool HitSphere(Ray, Sphere, ...) function,

have a int HitSpheres(Ray, SpheresSoA, ...) one, and then bool HitWorld() function just calls into that

(see commit).

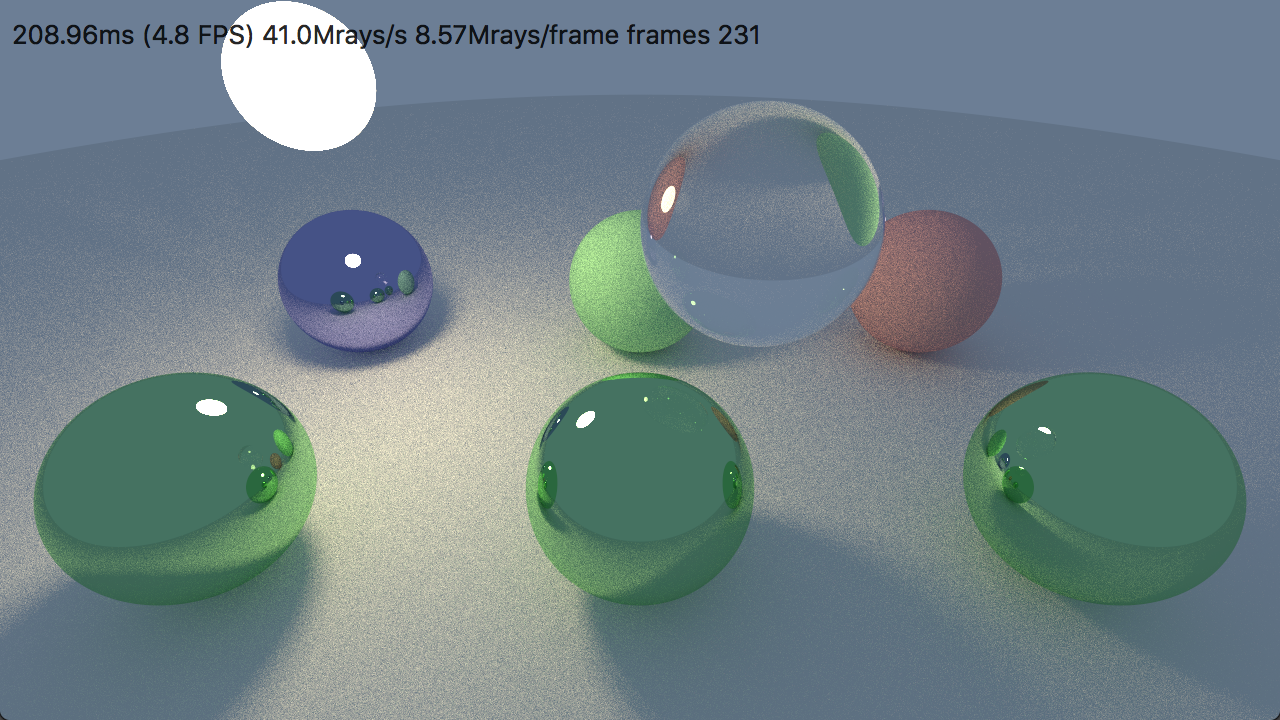

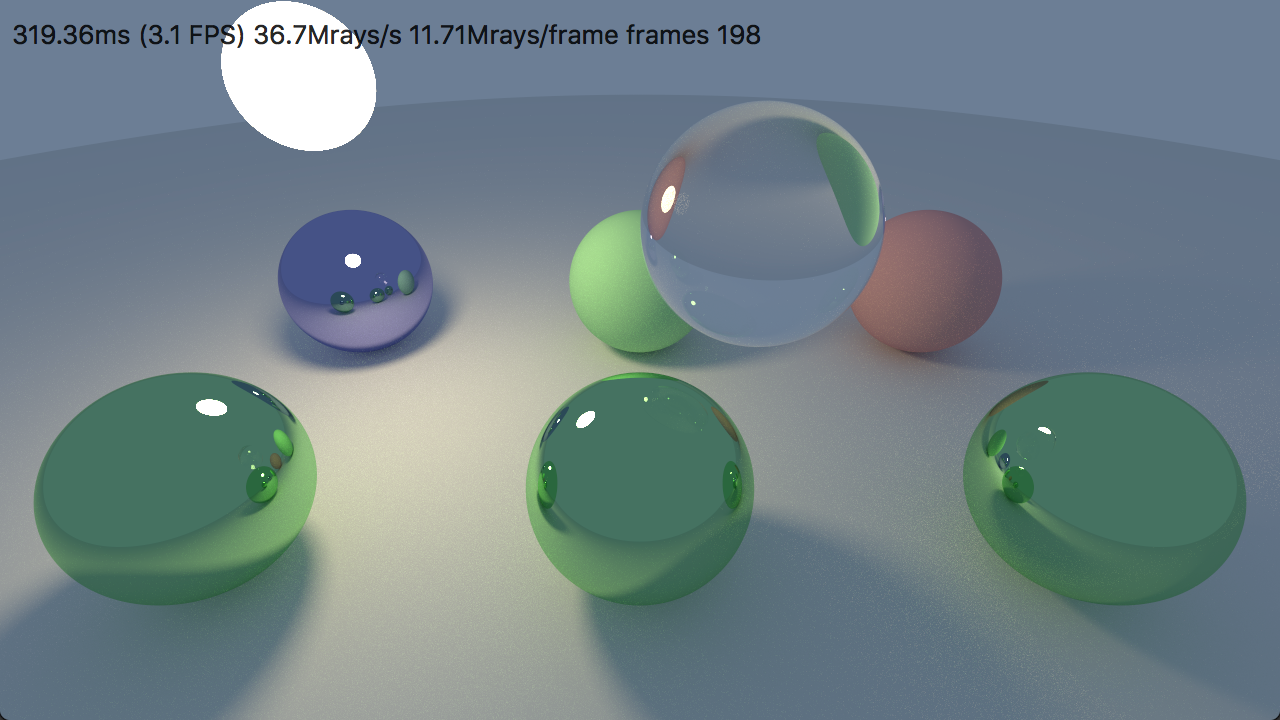

- PC: 171 -> 184 Mray/s.

- Mac: 42.6 -> 48.1 Mray/s.

Oh wow. This isn’t even doing any explicit SIMD; just shuffling data around, but the speed increase is quite nice!

And then I noticed that the HitSpheres function never needs to know the sphere radius (it needs only

the squared radius), so we might just as well put that into SoA data during preparation step

(commit).

PC: 184 -> 186, Mac: 48.1 -> 49.8 Mray/s. Not much, but nice for such an easy change.

…aaaand that’s it for today :) The above changes are in this PR,

or at 07-simd tag.

Learnings and what’s next

Learnings:

- You likely won’t get big speedups from “just” changing your Vector3 class to use SIMD.

- Just rearranging your data (e.g. AoS -> SoA layout), without any explicit SIMD usage, can actually speed things up! We’ll see later whether it also helps with explicit SIMD.

- Play around with compiler settings! E.g.

/fp:faston MSVC here brought a massive speedup.

I didn’t get to the potentially interesting SIMD bits. Maybe next time

I’ll try to make HitSpheres function use explicit SIMD intrinsics, and we’ll reflect on that. Until next time!