Optimizing Oklab gradients

An example how one might optimize Oklab color space gradients by… not doing anything related to Oklab itself!

The case at hand

I wrote about Oklab previously in the “gradients in linear space aren’t better” post. Now, let’s assume that the use case we have is this:

- We have some gradients,

- We need to evaluate them on a lot of things (particles, pixels, etc.),

- Gradient colors are specified in sRGB (sometimes called “gamma space”), as 8-bit/channel values,

- The evaluated gradient colors also have to be in sRGB, 8-bit/channel values. Why this, and not for example “linear” colors? Could be many reasons, ranging from “backwards compatibility” to “saving memory/bandwidth”.

What’s a gradient?

One simple way to represent a color gradient is to have color “keys” specified at increasing time values, for example:

struct Gradient

{

static constexpr int kMaxKeys = 8;

pix3 m_Keys[kMaxKeys]; // pix3 is just three bytes for R,G,B

float m_Times[kMaxKeys];

int m_KeyCount;

};

And the gradient like above would have 5 keys (red, blue, green, white, black) and key times 0.0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0.

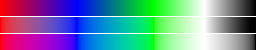

Ah! But how exactly the resulting gradient looks like depends on how we interpolate between the color keys, which neatly ties into why we’d want Oklab to begin with. The gradient above is directly interpolating the colors in sRGB space, i.e. “how everyone used to do it for many decades until recently”. Photoshop just added “Perceptual” (Oklab) and “Linear” interpolation modes, and the same gradient would look like this then – Classic (sRGB) at top, Perceptual (Oklab) in the middle, Linear at the bottom. See more examples in my previous blog post.

Assuming our gradient keys are sorted in increasing time order, code to evaluate the gradient might look like this:

pix3 Gradient::Evaluate(float t) const

{

// find the keys to interpolate between

int idx = 0;

while (idx < m_KeyCount-1 && t >= m_Times[idx+1])

++idx;

// we are past the last key; just return that

if (idx >= m_KeyCount-1)

return m_Keys[m_KeyCount-1];

// interpolate between the keys

float a = (t - m_Times[idx]) / (m_Times[idx+1] - m_Times[idx]);

return lerp(m_Keys[idx], m_Keys[idx+1], a); // interpolate in sRGB directly

}

Evaluating gradient in the three interpolation modes is exactly the same, all the way up to the last line:

- sRGB: just a

lerp, as above, - Linear: convert keys from sRGB to float Linear, lerp between them, convert back into fixed point sRGB,

- Oklab: convert keys from sRGB to float Linear, then into Oklab, lerp between them, convert back into float Linear, then back into fixed point sRGB.

We’re gonna try to be smart upfront and save a division by m_Times[idx+1] - m_Times[idx], by precalculating inverse of them

just once, i.e. m_InvTimeDeltas[i] = 1.0f / (m_Times[i + 1] - m_Times[i]). All the related source code is in

gradient.cpp,

mathlib.h,

oklab.cpp in my toy repository.

Initial performance

How much time does it take to evaluate a gradient with 7 color keys? We’re gonna do it 10 million times, on one thread, and measure time it takes in milliseconds.

| Platform | sRGB | Linear | Oklab |

|---|---|---|---|

| Windows, vs2022 | 125.2 | 619.2 | 2424.5 |

| Windows, clang 13 | 115.7 | 601.3 | 2405.5 |

| Linux, gcc 9.3 | 123.1 | 433.6 | 1567.2 |

| Linux, clang 10 | 106.6 | 411.4 | 1099.4 |

| Mac, clang 13 | 146.2 | 408.5 | 966.9 |

The Windows & Linux rows are on a PC (AMD Ryzen 5950X), Mac row is on MacBookPro (M1 Max). Windows is Win10 21H2, Linux is Ubuntu 20 via WSL2, macOS is 12.1. Compiler options are -O2 for gcc&clang, Release for visual studio, everything else left at defaults.

Takeaways so far: Linear gradient interpolation is 3-6x slower than sRGB, and Oklab is 10-20x slower than sRGB. There are some variations between platforms & compilers, but overall patterns are similar.

Profiling Windows build says that majority of the time in Linear & Oklab cases is spent raising numbers to a power:

- Linear spends 481ms inside

powf(), - Oklab spends 1649ms inside

cbrtf(), and 515ms insidepowf().

Stop doing the same work repeatedly

That’s often a good performance optimization advice. Note the tail of gradient Oklab evaluation function code:

// to-Linear -> to-Oklab -> lerp -> to-Linear -> to-sRGB

float3 ca = pix_to_float(m_Keys[idx]);

float3 cb = pix_to_float(m_Keys[idx+1]);

ca = sRGB_to_Linear(ca);

cb = sRGB_to_Linear(cb);

ca = Linear_sRGB_to_OkLab_Ref(ca);

cb = Linear_sRGB_to_OkLab_Ref(cb);

float3 c = lerp(ca, cb, a);

c = OkLab_to_Linear_sRGB_Ref(c);

c = Linear_to_sRGB(c);

return float_to_pix(c);

…all the calculations up until the lerp line do not depend on the gradient evaluation time at all! We could,

instead of just storing gradient color keys in sRGB, also precalculate their Linear and Oklab values. This does add

some extra storage space into Gradient object, but perhaps saves a bit of computation.

So let’s do this (commit), and then the code above turns into:

float3 c = lerp(m_KeysOkLab[idx], m_KeysOkLab[idx+1], a);

c = OkLab_to_Linear_sRGB_Ref(c);

c = Linear_to_sRGB(c);

return float_to_pix(c);

And this gives the following performance numbers:

| Platform | sRGB | Linear | Oklab |

|---|---|---|---|

| Windows, vs2022 | 124.9 | 271.1 | 321.8 |

| Linux, clang 10 | 107.0 | 196.0 | 277.7 |

| Mac, clang 13 | 141.8 | 224.4 | 286.8 |

Linear is now only 1.5-2.1x slower than sRGB, and Oklab is 2.0-2.6x slower than sRGB. Still slower, but not “orders of magnitude” slower anymore. Nice!

Profiling Windows build says that Linear and Oklab still spend most of their remaining time inside powf() though, 152ms and 180ms respectively.

This is all inside Linear_to_sRGB function. Ok, now what?

Table based Linear to sRGB conversion

Notice that we effectively need to convert from a Linear float into a fixed point (8-bit) sRGB. Right now we do that with a generic “linear float -> sRGB float” function, followed by a “normalized float -> byte” function. But turns out, people smarter than me figured out this can be done in a more optimal way, a decade ago. Of course that was Fabian ‘ryg’ Giesen in this gist file. It has extensive comments there, go take a read.

Let’s try this (commit):

| Platform | sRGB | Linear | Oklab |

|---|---|---|---|

| Windows, vs2022 | 126.9 | 148.9 | 173.4 |

| Linux, clang 10 | 107.7 | 132.7 | 164.6 |

| Mac, clang 13 | 140.1 | 157.7 | 180.9 |

Linear is now 1.2x slower than sRGB, and Oklab is 1.3-1.5x slower than sRGB. Yay!

Removing one matrix multiply

All the way up until now, we have not actually modified anything about Oklab calculations. The code & math we’re using are coming directly from Oklab post.

But! If all we need is to linearly blend between Oklab colors, we can simplify this a bit. For our particular use case (evaluating gradients), we don’t need some bits of Oklab: we’re not interested whether the Oklab numbers predict lightness, or whether “distances” between said numbers match perceived color differences. We just need to “nicely” interpolate between the gradient color keys.

Note that Linear -> Oklab conversion is effectively “multiply by matrix M1, apply cube root, multiply by matrix M2”. The opposite conversion is “multiply by inverse of M2, raise to 3rd power, multiply by inverse of M1”. We’re only going to be linearly interpolating between Oklab colors, so we can drop the multiplies related to matrix M2 and the result will be the same (minus a tiny amount of floating point rounding). That is, leave only the “multiply by matrix M1, apply cube root” and “raise to 3rd power, multiply by inverse of M1” parts.

Technically our gradient color keys are no longer in Oklab, but rather in LMS, but anyway the gradient evaluation result is the same.

And here are the results with this (commit):

| Platform | sRGB | Linear | Oklab* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Windows, vs2022 | 125.4 | 144.6 | 167.3 |

| Linux, clang 10 | 108.4 | 133.0 | 151.3 |

| Mac, clang 13 | 143.7 | 162.0 | 182.5 |

Linear is now only 1.1-1.2x slower than sRGB, and Oklab is 1.3-1.4x slower than sRGB. So dropping a matrix multiply made things a tiny bit faster.

And that’s it for now! Maybe some other time I’ll write about evaluating gradients using SIMD, and see what happens.