"Parallel for" in Apple's GCD

I was checking out OpenSubdiv and noticed that on a Mac it’s not exactly “massively parallel”. Neither of OpenGL backends work (transform feedback one requires GL 4.2, and compute shader one requires GL 4.3 - but Macs right now can only do GL 3.2), OpenCL backend is much slower than the CPU one (OS X 10.7, GeForce GT 330M) for some reason, I don’t have CUDA installed so didn’t check that one, and OpenMP isn’t exactly supported by Apple’s compilers (yet?). Which leaves OpenSubdiv doing simple single threaded CPU subdivision.

This isn’t webscale multicorescale! Something must be done!

Apple platforms might not support OpenMP, but they do have something called Grand Central Dispatch (GCD). Which is supposedly a fancy technology to make multicore programming very easy – here’s the original GCD unveiling. Seeing how easy it is, I decided to try it out.

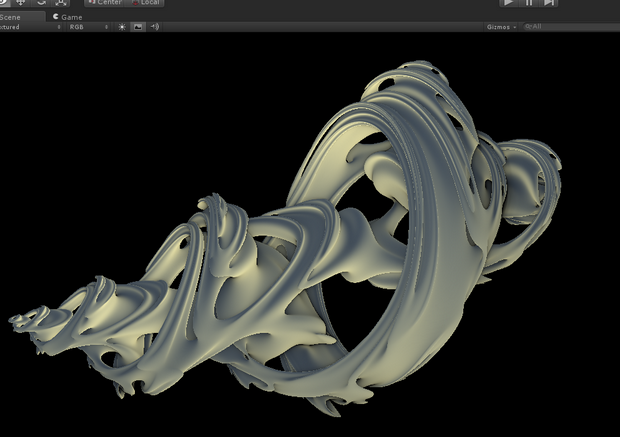

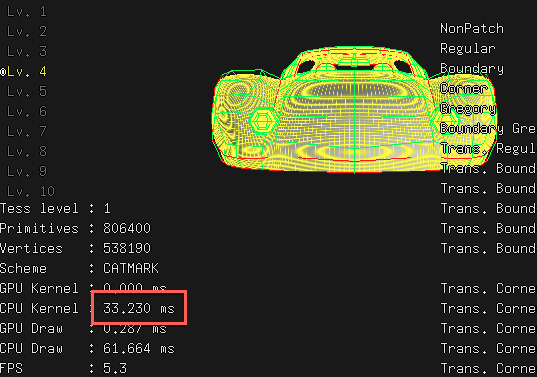

As a baseline, single threaded “CPU” subdivision kernel takes 33 milliseconds to compute 4th subdivision level of a “Car” model:

OpenMP dispatcher in OpenSubdiv

Subdivision in OpenSubdiv is computed by running several loops over data: loop to compute new edge positions, new face positions, new vertex positions etc. Fairly standard stuff. Each loop iteration is completely independent from others, for example:

void OsdCpuComputeEdge(/*...*/ int start, int end) {

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

// compute i-th edge, completely independent of all other edges

}

}

So of course OpenMP version just trivially says “hey, this loop is parallel!”:

void OsdOmpComputeEdge(/*...*/ int start, int end) {

#pragma omp parallel for //<-- only this line is different!

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

// compute i-th edge

}

}

And then OpenMP-aware compiler and runtime will decide how to run this loop best over multiple CPU cores available. For example, it might split the loop into as many subsets as there are CPU cores, run these subsets (“jobs”) on its worker threads for these cores, and wait until all of them are done. Or it might split it up into more jobs, so that if the job lenghts will end up being different, it will still have some jobs to process on the other cores. This is all up to the OpenMP runtime to decide, but generally for large completely parallel loops it does a pretty good job.

Except, well, OpenMP doesn’t work on current Xcode 4.5 compiler (clang).

Initial parallel loop using GCD

GCD documentation suggests using dispatch_apply to submit a number of jobs at once; see Performing Loop Operations Concurrently section. This is easy to do:

void OsdGcdComputeEdge(/*...*/ int start, int end, dispatch_queue_t gcdq) {

// replace for loop with:

dispatch_apply(end-start, gcdq, ^(size_t blockIdx){

int i = start+blockIdx;

// compute i-th edge

});

}

See full commit here. That was easy. And slower than single threaded: 47ms with GCD, compared to 33ms single threaded. Not good.

OpenMP looks at the whole loop and hopefully partitions it into sensible count of subsets for parallel execution. Whereas GCD’s dispatch_apply submits each iteration of the loop to be executed in parallel. This “submit stuff to be executed on my worker threads” is naturally not a free operation and incurs some overhead. In our case, each iteration of the loop is fairly simple, it pretty much does weighted average of some vertices. Dispatch overhead here is probably higher than the actual work that we’re trying to do!

Better parallel loop using GCD

Of course the solution here is to batch up work items. Imagine that this loop processes, for example, 16 items (vertices, edges, …), then goes to next 16, and so on. These “packets of 16 items” would be what we dispatch to GCD. At the end of the loop, we might need to handle the remaining ones, if the number of iterations was not a multiple of 16. In fact, this is exactly what GCD documentation suggests in Improving on Loop Code.

All OpenSubdiv CPU kernels take “start” and “end” parameters that are essentially indices into an array of where to do the processing. So from our GCD blocks we can just call the regular CPU functions (see full commit):

const int GCD_WORK_STRIDE = 16;

void OsdGcdComputeEdge(/*...*/ int start, int end, dispatch_queue_t gcdq) {

// submit work to GCD in parallel

const int workSize = end-start;

dispatch_apply(workSize/GCD_WORK_STRIDE, gcdq, ^(size_t blockIdx){

const int start_i = start + blockIdx*GCD_WORK_STRIDE;

const int end_i = start_i + GCD_WORK_STRIDE;

OsdCpuComputeFace(/*...*/, start_i, end_i);

});

// do trailing block that's less than our batch size

const int start_e = end - workSize%GCD_WORK_STRIDE;

const int end_e = end;

if (start_e < end_e)

OsdCpuComputeFace(/*...*/, start_e, end_e);

}

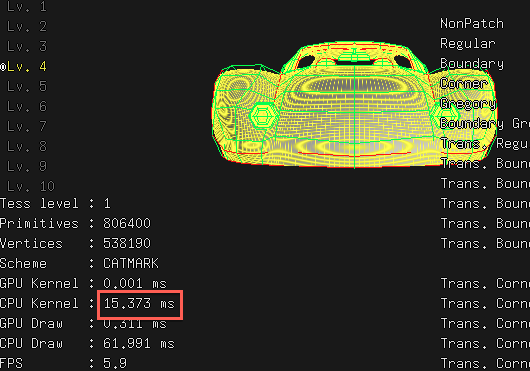

This makes 4th subdivision level of the car model be computed in 15ms:

So that’s twice as fast as single threaded implementation. Is that good enough or not? My machine is a dual core (4 thread) one, so it is within my ballpark of expectations. Maybe it could go higher, but for that I’d need to do some profiling.

But you know what? Take a look at the other numbers - 62 milliseconds are spent on “CPU Draw”, so clearly that takes way more time than actual subdivision now. Fixing that one will have to be for another time, but suffice to say that reading data from GPU vertex buffers back into system memory each frame might not be a recipe for efficiency.

There’s at least one place in the above “GCD loop pattern” (hi Christer!) that might be improved: dispatch_apply waits until all submitted jobs are done. But to compute the trailing block we don’t need to wait for the other ones. The trailing block could be incorporated into the dispatch_apply loop, with better computation of end_i variable. Some other day!