Replacing a live system is really hard

So! Turns out my “two years in a build team” post was almost the end of my time there :) I’ve started a new thing & new work area, and am wrapping up some of my leftover build team work as we speak. But! I wanted to write about one particular aspect of this build system work, which took almost three years in total.

Three. Years.

That’s a really long time, and that’s how long it took for us to switch from “the build system we had previously” to “the build system we have now”. Turns out, replacing a system in an ever-moving product is really, really, REALLY hard.

Sometimes I see that whenever people dream up some New Fancier Better system, they think that making this new system is the where most of the work will go into. In my experience (in build system, but also in a handful of other occasions), in addition to developing the new things, you also have to cover these:

- While you will be busy doing new stuff, how will you keep up with changes to the old stuff? In a build system, people will keep on adding new files, libraries to be built, will tweak compiler flags, change preprocessor defines, update SDK/compiler versions and so on. Same with any other area – the old system is “live”, being used and being changed over time; maybe data for the old system is still being produced by someone out there. How will you transition all that?

- How will the new system be rolled out, in a way that everything keeps on working, all the time? We have hundreds of developers on this codebase, a lot of automated processes running (builds, tests, packaging etc.), and if everyone loses even a day of work due to some mess-up, that’s a massive cost. Really risky changes have to be rolled out incrementally somehow, and only rolled out to “everyone” when all the large issues are found and fixed.

So here’s a story in how we did it! I don’t know if the chosen approach is good or bad; it seems to have worked out fine.

2016 May, “Jam with C#” project at Hackweek.

At Unity Hackweek 2016, one of the projects was “what if instead of Jam syntax to describe the build, we had C#?”. There’s a short video of it here:

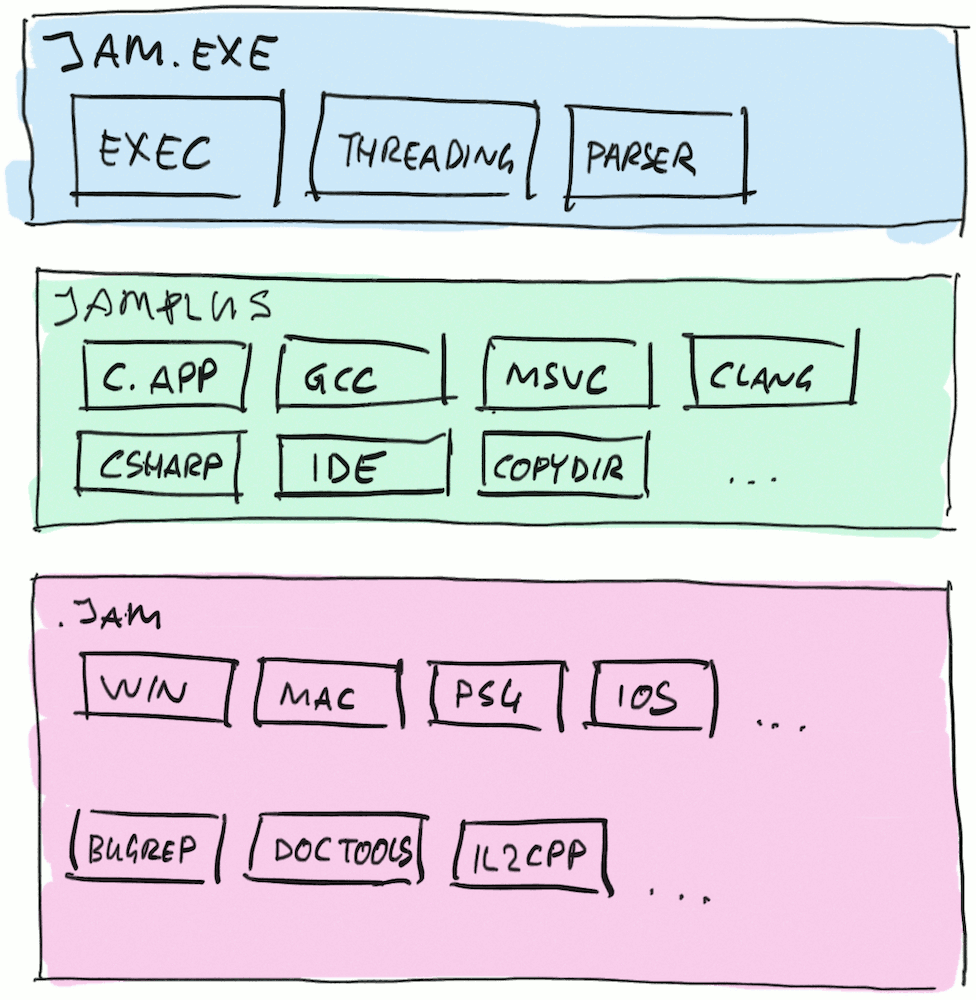

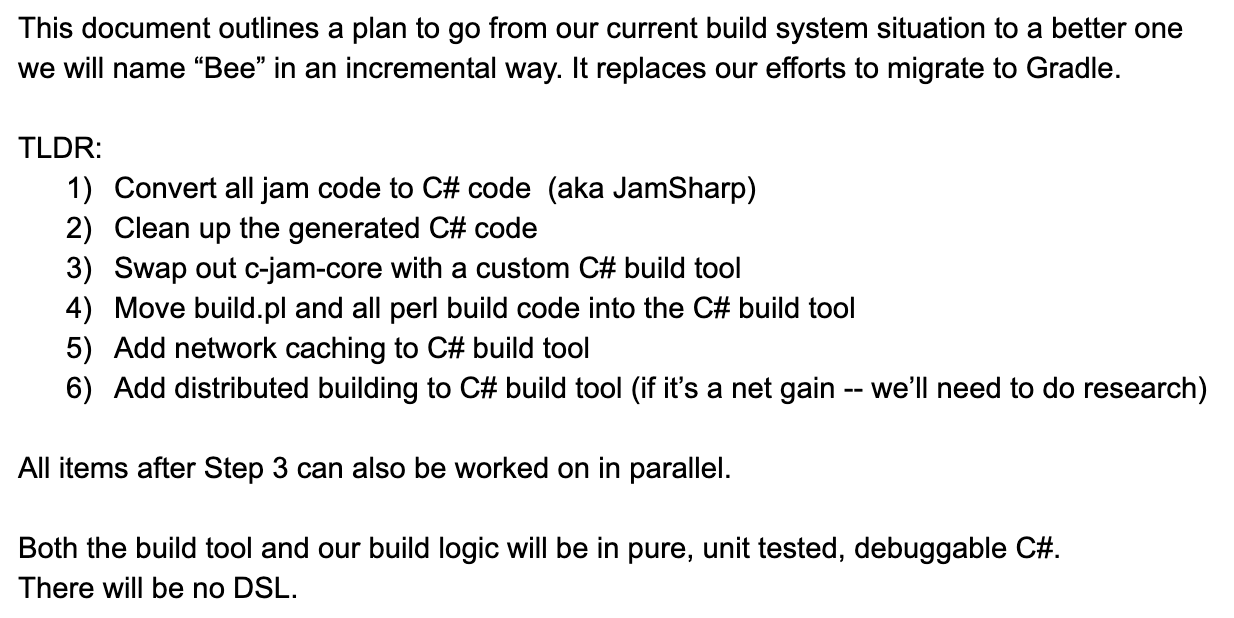

We used a Jam-based build system called JamPlus to build everything inside Unity since about 2010. Overall the whole setup looks like this:

- There is an actual “build engine”, the

jam.exeitself. This piece knows how to parse*.jamfiles that describe the build, find which things need to be updated in order to build something, and execute these builds commands in parallel where possible. - “JamPlus” is a bunch of rules written on top of that, in a combination of Jam and Lua languages. These are helper utilities, like “finding a C++ compiler” and describing basic structure of a C/C++ program, etc. JamPlus can also generate IDE project files for Visual Studio, Xcode and so on.

- And then we have a bunch of our own

*.jamfiles, that describe pieces and platforms of Unity itself. From simple things like “this is a list of C++ files to compile, and here are the compiler flags”, to more involved things that are mostly about generating code at build time.

Jam language syntax is very compact, but also “interesting” – for example, it needs whitespace between all tokens; and yes that means space before every semicolon, or otherwise a lot of confusing messages you will get. Here’s a random example I found:

rule ConvertFile CMD : DEST : SOURCE_INPUT : GENERATED_INPUT

{

INPUT = $(SOURCE_INPUT:G=hlslang) ;

GENERATED_INPUT = $(GENERATED_INPUT:G=hlslang) ;

DEST = $(DEST:G=hlslang) ;

MakeLocate $(SOURCE_INPUT) : $(SEARCH_SOURCE) ;

MakeLocate $(GENERATED_INPUT:D=) : $(LOCATE_TARGET)/$(GENERATED_INPUT:D) ;

MakeLocate $(DEST:D=) : $(LOCATE_TARGET)/$(DEST:D) ;

Clean clean : $(DEST) ;

UseFileCache $(DEST) ;

Depends $(DEST) : $(SOURCE_INPUT) $(GENERATED_INPUT) ;

$(CMD) $(DEST) : $(SOURCE_INPUT) $(GENERATED_INPUT) ;

ScanContents $(DEST) ;

return $(DEST) ;

}

So at this hackweek, what they did was embed C# (via Mono) directly into jam.exe, and make it be able

to run C# code to describe everything there is to build, instead of parsing a Jam language file. They also

wrote a converted from Jam language into C# language. If that sounds a bit crazy, that’s because it is, but

eh, who here has not embedded C# into a piece of software written in 1993?

And so all of *.jam files (our own build code, but also most of JamPlus rules) get turned into C# files, but

functionally nothing else changes. The auto-generated C# of course does not look much better; in fact at this

point it’s more verbose than original Jam code:

static JamList ConvertFile(JamList CMD, JamList DEST, JamList SOURCE_INPUT, JamList GENERATED_INPUT)

{

DEST = DEST.Clone();

GENERATED_INPUT = GENERATED_INPUT.Clone();

Vars.INPUT.Assign(SOURCE_INPUT.SetGrist("hlslang"));

GENERATED_INPUT.Assign(GENERATED_INPUT.SetGrist("hlslang"));

DEST.Assign(DEST.SetGrist("hlslang"));

Jambase.MakeLocate(SOURCE_INPUT, Vars.SEARCH_SOURCE);

Jambase.MakeLocate(GENERATED_INPUT.SetDirectory(""), Combine(Vars.LOCATE_TARGET, "/", GENERATED_INPUT.GetDirectory()));

Jambase.MakeLocate(DEST.SetDirectory(""), Combine(Vars.LOCATE_TARGET, "/", DEST.GetDirectory()));

Jambase.Action_Clean("clean", DEST);

InvokeJamRule("UseFileCache", DEST);

Depends(DEST, JamList(SOURCE_INPUT, GENERATED_INPUT));

InvokeJamRule(CMD, DEST, JamList(SOURCE_INPUT, GENERATED_INPUT));

InvokeJamRule("ScanContents", DEST);

return DEST.Clone();

}

However with some cleanups and good IDEs (♥Rider) you can get to more legible

C# fairly quickly eventually:

static void ConvertFile(string cmd, NPath dest, NPath sourceInput, NPath generatedInput)

{

InvokeJamAction(cmd, dest, JamList(sourceInput, generatedInput));

// Tell Jam that the generated bison/flex file "includes" the original tempate grammar files,

// meaning it will include whatever regular C headers these include too, to detect needed rebuilds.

Includes(dest, sourceInput);

Depends(dest, JamList(sourceInput, generatedInput));

Needs(dest, BuildZips.Instance.FlexAndBison.ArtifactVersionFile);

}

2016, actual work starts

Hackweeks are a lot of fun, and one can get very impressive results by doing the most interesting parts of the project. However, for actual production, “we’ll embed Mono into Jam, and write a language converter that kinda works” is not nearly enough. It has to actually work, etc. etc.

Anyway, a couple months after hackweek experiment, our previous effort to move from Jam/JamPlus to

Gradle was canceled, and this new “Jam with C#” plan was greenlit.

Anyway, a couple months after hackweek experiment, our previous effort to move from Jam/JamPlus to

Gradle was canceled, and this new “Jam with C#” plan was greenlit.

It took until February of next year when this “Jam build engine, but build code is written in C#” was landed to everyone developing Unity. How did we test it?

- Had a separate branch that tracks mainline, where on the build farm it was doing two builds at once:

- First, regular Jam build with the

*.jambuild code, and dumped whole Jam build graph structure, - Second one, with all the

*.jamcode automatically converted to C#, and dumped whole Jam build graph structure, - Checking that the two builds graphs were identical for each and every build target/platform that we have.

- First, regular Jam build with the

- Had some developers at Unity opt-in to the new “Jam#” build code for a few months, to catch any possible issues. Especially the ones that are not tested/covered by the build farm, e.g. “are Visual Studio project files still generated just like before?”.

- Before the final roll-out of “all .jam files are gone, .jam.cs files are in”, we also had a tool that would help anyone who had a long-lived branch that they want to land to mainline. They might have changed build code in Jam language, but after the C# roll-out their changes would have nowhere to merge! So there was a “give an old .jam file, we’ll get you the converted C# file back” tooling for that case.

And so in 2017 February we rolled out removal of all the old *.jam files, and the (horrible looking) auto-converted

C# build code landed:

2017, starting to take advantage of this C# thing

Auto-converted-Jam-to-C# is arguably not much better. More verbose, actually kinda harder to read, but there

are some upsides. Statically typed programming language! Great IDEs and debuggers! You have more data types besides

“list of strings”! A lot of people inside Unity know C#, whereas “I know Jam” is not exactly common! And so on.

Auto-converted-Jam-to-C# is arguably not much better. More verbose, actually kinda harder to read, but there

are some upsides. Statically typed programming language! Great IDEs and debuggers! You have more data types besides

“list of strings”! A lot of people inside Unity know C#, whereas “I know Jam” is not exactly common! And so on.

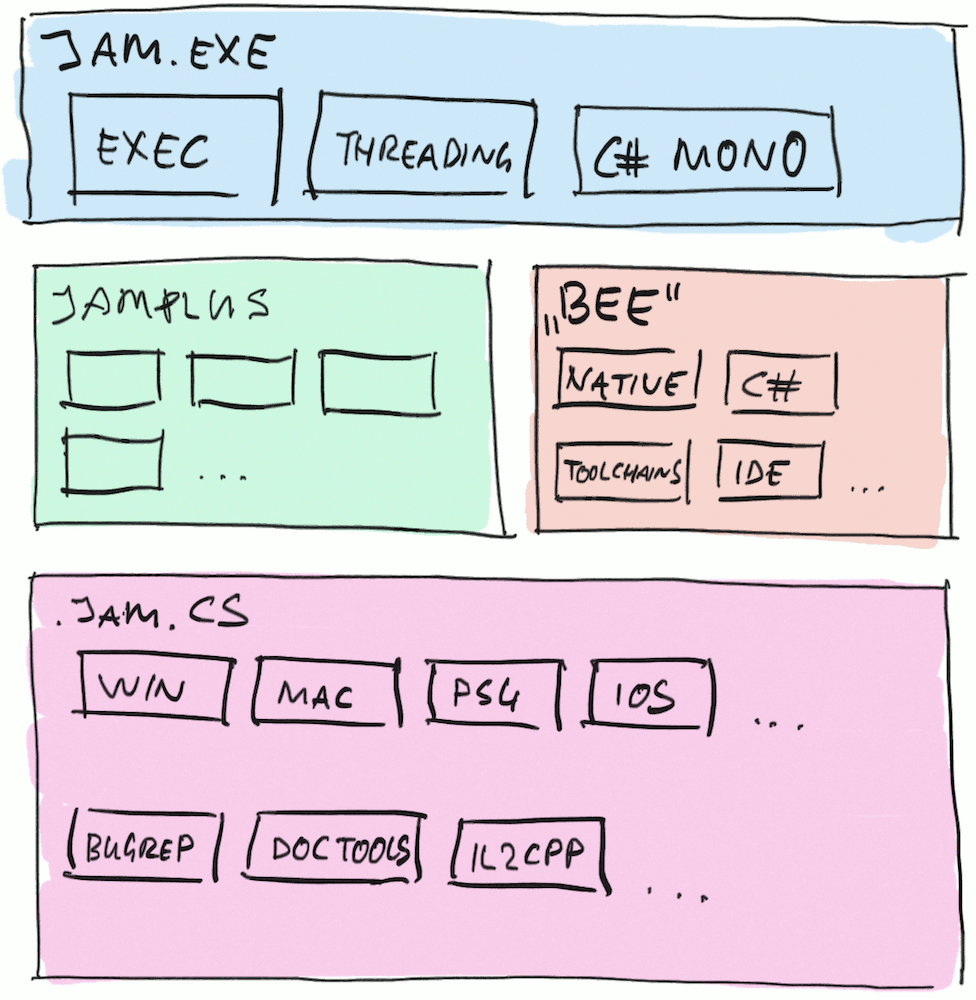

And so we started writing new C#-based APIs to express “how to build a program” rules, which we call “Bee” (you’d have to ask @lucasmeijer about the name).

We were also rewriting IDE project files generation from the Lua-based one in JamPlus to, well, C#. My blog posts from 2017 relating to Visual Studio project files (this one or that one) might have been because I was doing it at the time :)

Of course at this point all of our own build code still used the old JamPlus-but-now-C# APIs to express how things need to be built. And we began taking all these pieces and converting them to use the new Bee build APIs:

This took much longer than initially expected, primarily because OMG you would not believe what a platform build code might be doing. Why is this arcane compiler flag used here? No one remembers! But who knows what might break if you change it. Why these files are being copied over there, ran through this strange tool, signed in triplicate, sent in, sent back, queried, lost, found, subjected to public inquiry, lost again, and finally buried in soft peat for three months and recycled as firelighters? Who knows! So there was a lot of that going on, inside each and every non-trivial build platform and build target that we had.

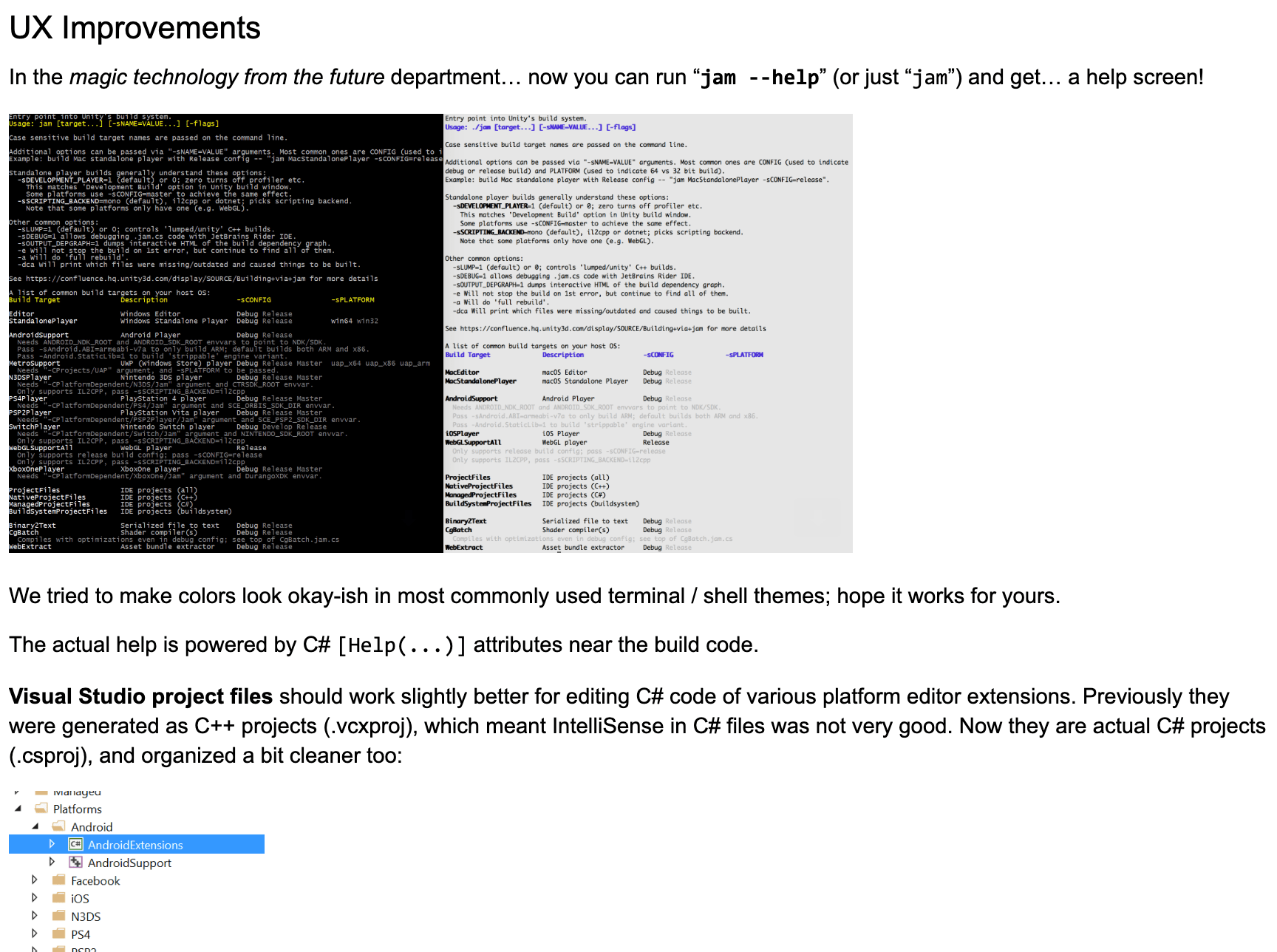

We also did a lot of work in other build areas, be it improving UX (error messages, colors, …), developing a system for downloading binary artifacts as part of the build, upgrading and packaging up compiler toolchains, experimenting with Ninja build backend instead of Jam (more on that later), optimizing codebase build times in general, improving project files and so on.

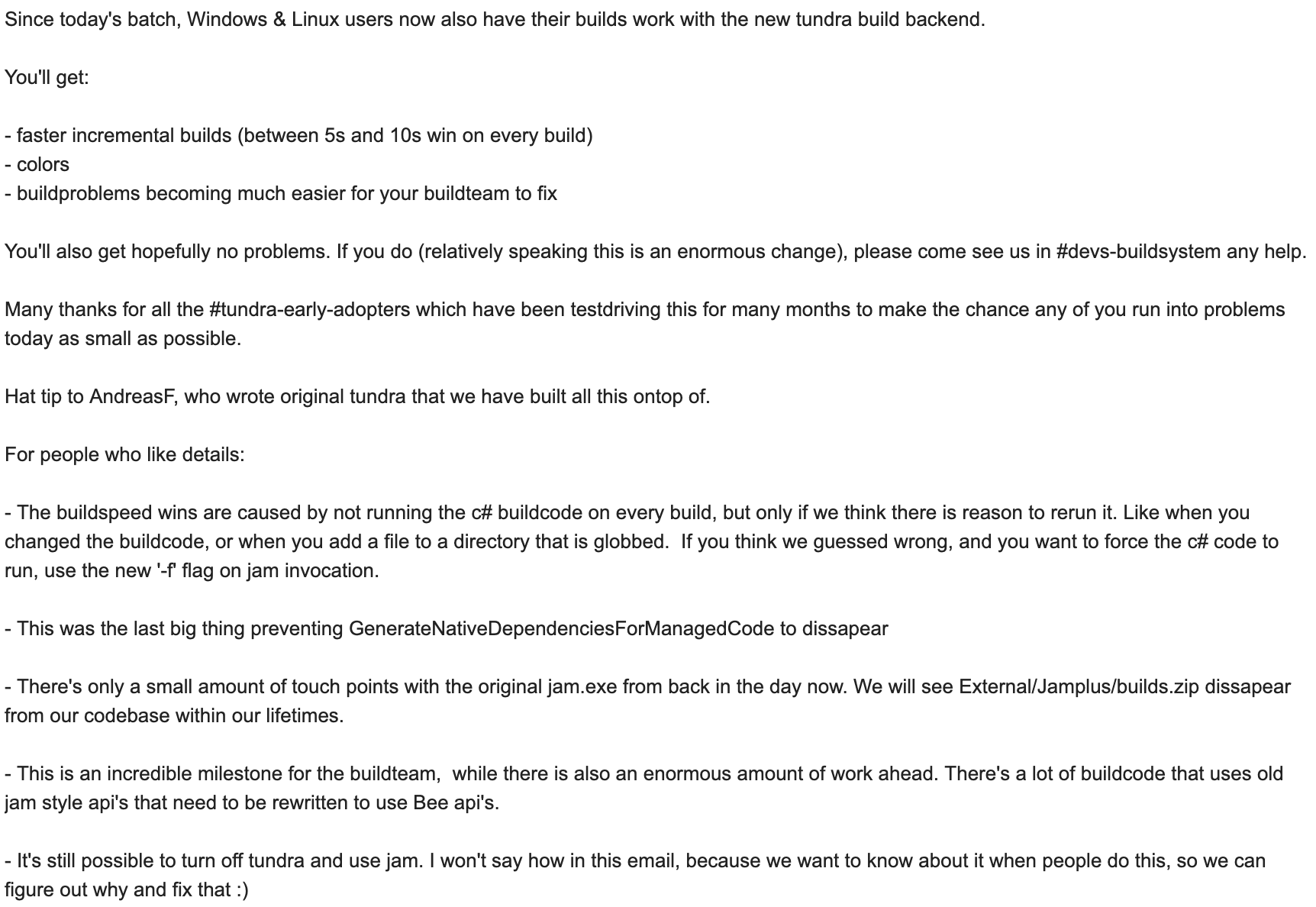

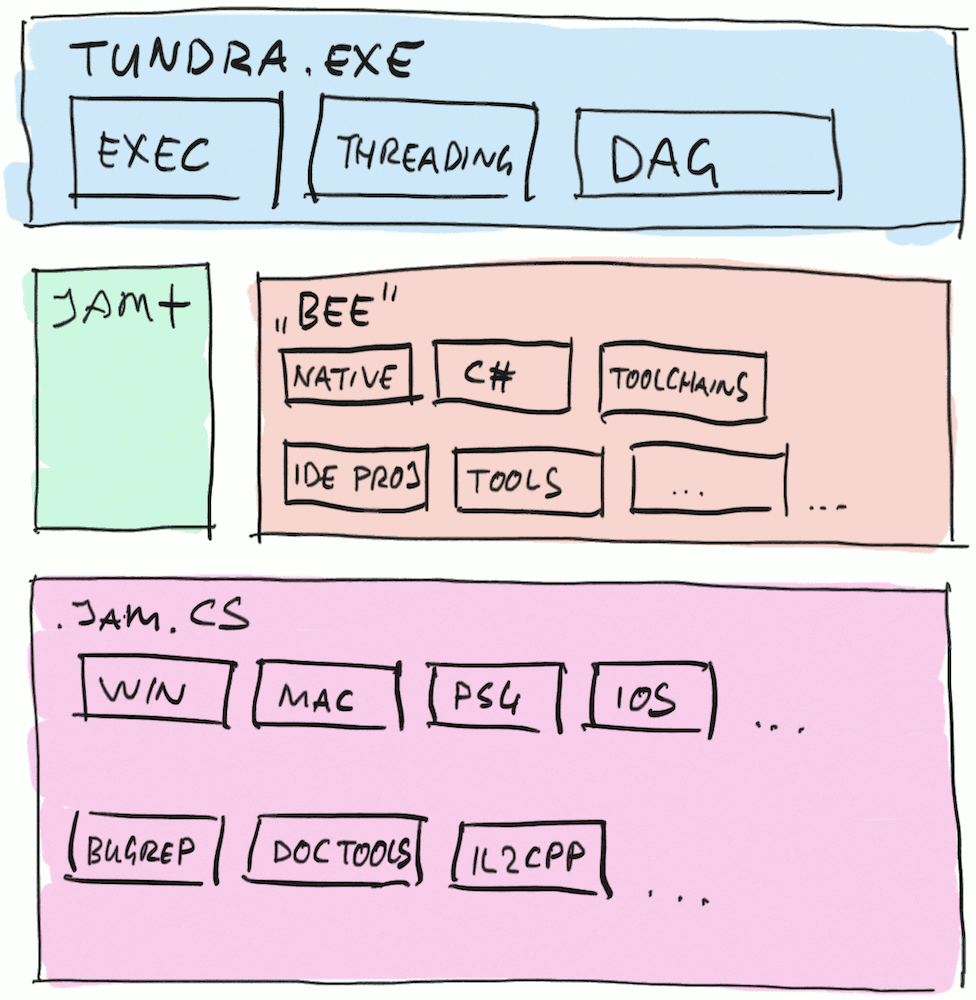

2018, Jam switched to Tundra backend

After some experiments with Ninja backend, we settled upon Tundra

(our own fork) and replaced the Jam build backend with it.

After some experiments with Ninja backend, we settled upon Tundra

(our own fork) and replaced the Jam build backend with it.

The change was fairly hard to verify that “it works exactly the same as before”, because Tundra does not work exactly the same as Jam. One might think that all build systems are “have some rules, and a build dependency graph, and they execute the build actions”, but it’s a bit more complexicated than that. There’s a nice paper from Microsoft Research, “Build Systems à la Carte”, that categorizes build systems by type of dependencies they support (static vs dynamic), scheduling approach, early cutoff support, etc. Specifically, Tundra’s scheduler is different (I think it’s “restarting” one as per that paper, whereas Jam’s is “topological”).

In practice, at least in our codebase this means that Tundra very often rebuilds less things compared to Jam, especially when things involve files generated during build time. Since the order of build steps and even the amount of them is different between Tundra and Jam, we could not just build simple validation suite like “build everything with both, compare that they did exact same steps”.

So what we did was rely on the automated builds/tests that we already had for the product itself, and also on volunteer developers

inside Unity to try out Tundra locally. Since 2018 January people could opt-in to Tundra by adding a tiny local environment change,

and report any & all findings. We started with a handful of people, and over coming months it grew to several dozen. In late May it

got turned on by default (still with ability to opt-out) for everyone on Mac, and next month everyone got Tundra switched on. Some time

later remains of

So what we did was rely on the automated builds/tests that we already had for the product itself, and also on volunteer developers

inside Unity to try out Tundra locally. Since 2018 January people could opt-in to Tundra by adding a tiny local environment change,

and report any & all findings. We started with a handful of people, and over coming months it grew to several dozen. In late May it

got turned on by default (still with ability to opt-out) for everyone on Mac, and next month everyone got Tundra switched on. Some time

later remains of jam.exe got actually removed.

2019, current state

Today in our main code repository,

Today in our main code repository, jam.exe is long gone, and almost all of remains of JamPlus-converted C# code are gone.

Compared to the build state three years ago, a lot of nice build related tools were built (some I wrote about in the previous blog post), and in general I think various aspects of build performance, reliability, UX, workflow have been improved.

As a side effect, we also have this fairly nice build system (“Bee”) that we can use to build things outside of our main code repository! So that’s also used to build various external libraries that we use, in various plugins/packages, and I think even things like Project Tiny use it for building actual final game code.

So all that’s nice! But oh geez, that also took a lot of time. Hence the blog post title.