Daily Pathtracer 11: Buffer-Oriented

Introduction and index of this series is here.

I’ll try to restructure the path tracer a bit, from a “recursion based” approach into a “buffer based” approach.

“But why?” I had a thought of playing around with the new Unity 2018.1 async/batched raycasts for a path tracer, but that API is built on a “whole bunch of rays at once” model. My current approach that does one ray at a time, recursively, until it finishes, does not map well to it.

So let’s do it differently! I have no idea if that’s a good idea or not, but eh, let’s try anyway :)

Recursive (current) approach

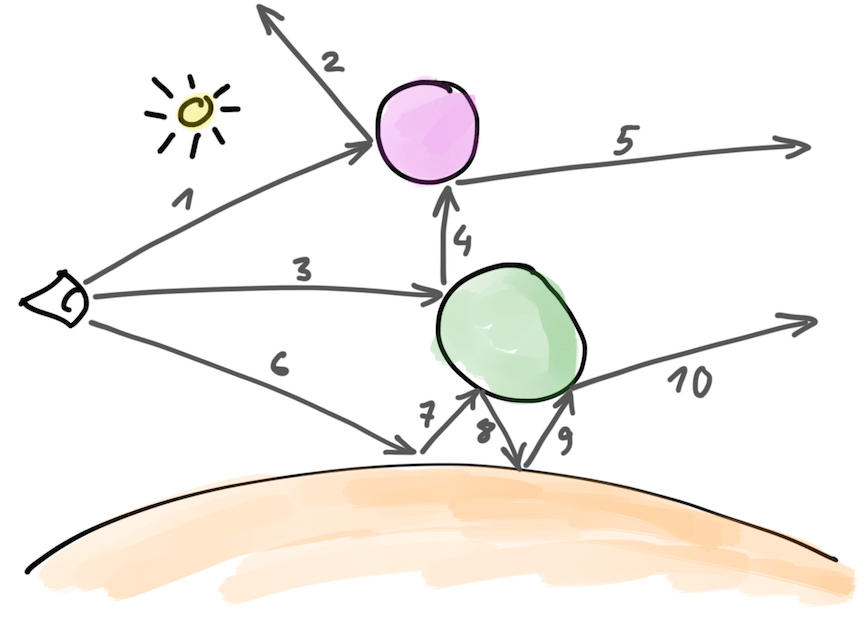

Current approach is basically like the diagram above. We start with casting some ray (“1”), it hits something, is scattered, we continue with the scattered ray (“2”), until maximum ray depth is reached or ray hits “sky”. Next, we start another camera ray (“3”), that is scattered (“4”), and so on. It basically goes one ray at a time, in a depth-first traversal order (using recursion in my current CPU implementations; and iterative loop in GPU implementations).

Buffer-based approach

I don’t know if “buffer based” is a correct term… I’ve also seen “stream ray tracing” and “wavefront ray tracing” which sound similar, but I’m not sure they mean exact same thing or just somewhat similar idea. Anyway…

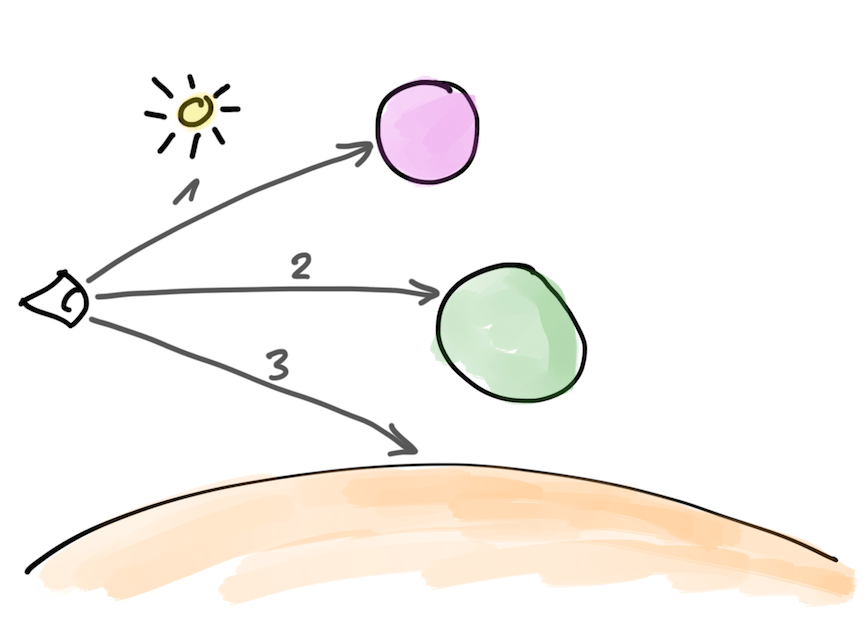

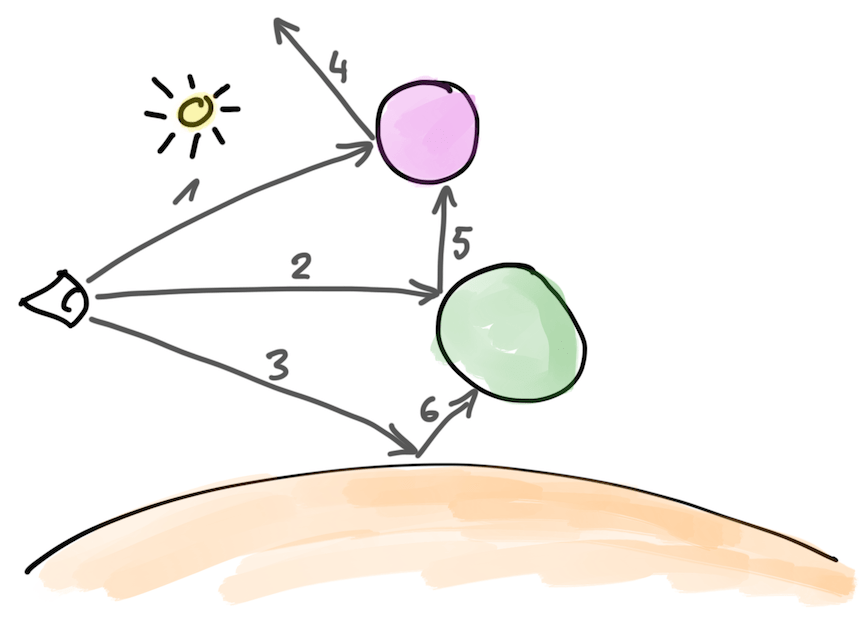

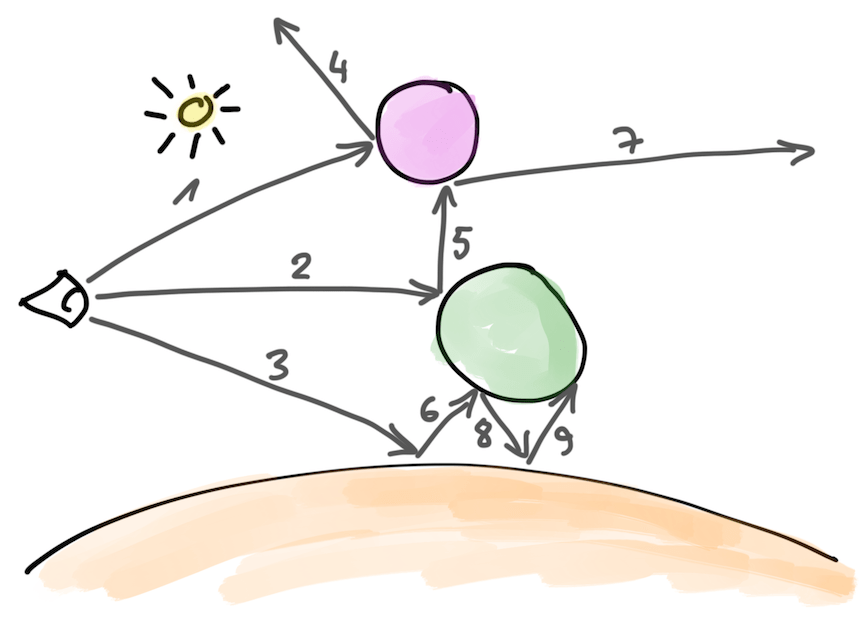

One possible other approach would be to do breadth-first traversal of rays. First do all primary (camera) rays, store their hit information into some buffer (hence “buffer based”). Then go look at all these hit results, scatter or process them somehow, and get a new batch of rays to process. Continue until maximum depth is reached or we’re left with no rays to process for some other reason.

Morgan McGuire’s G3D path tracer seems to be structured similarly, as well as Laine, Karras, Aila “Megakernels Considered Harmful: Wavefront Path Tracing on GPUs”, from my quick look, suggests something along those lines.

So the approach would basically be:

// generate initial eye rays

buffer1 = GenerateCameraRays();

// while we still have rays to do

while (!buffer1.empty())

{

buffer2.MakeEmpty();

// for each ray in current bounce, raycast and evaluate it

foreach (Ray r in buffer1)

{

hit = HitWorld(r);

if (hit)

{

image[ray.pixel] += EvaluateMaterial();

// add rays for next bounce

AddScatteredRayTo(buffer2);

AddShadowRayTo(buffer2);

}

else

{

image[ray.pixel] += EvaluateSkyColor();

}

}

// swap buffers; proceed to next bounce

swap(buffer1, buffer2);

}

What information we need to track per-ray in these buffers? From what I can see, the current path tracer needs to track these:

struct Ray

{

Ray ray; // the ray itself, duh (origin + direction)

Color atten; // current attenuation along the ray

int pixelIndex; // which image pixel this ray is for

int depth; // ray bounce depth, to know when we hit maximum bounces

int lightID; // for light sampling ("shadow") rays only: which light this ray is cast towards

bool shadow; // is this a light sampling ("shadow") ray?

bool skipEmission; // should material emission, if hit by this ray, be ignored

};

How large these ray buffers should be? In the simplest form, let’s just preallocate “maximum possible space”

we think we’re going to need. One buffer for the whole image would be

Width * Height * SamplesPerPixel * (1 + MaxShadowRays) in size (one ray can scatter; plus several shadow rays).

And we need two of these buffers, since we’re writing into a new one while processing current one.

Implementation of the above for C++ is in this commit. It works correctly, now, what’s the performance, compared our previous state? PC: 187→66 Mray/s, Mac: 41.5→39.5 Mray/s. Huh what? This is almost three times slower on PC, but almost no performance change on Mac?!

What’s going on?

Well, for one, this approach now has a whopping 1800 megabytes (yeah, 1.8GB) of buffers to hold that ray data; and each bounce iteration reads from these giant buffers, and writes into them. The previous approach had… none of such thing; the only memory traffic it had was blending results into the final pixel buffer, and some (very small) arrays of spheres and materials.

I haven’t actually dug into this deeper, but my guess on “why Mac did not become slower” is that 1) if this is limited by RAM bandwidth, then the speed of RAM between my PC & Mac is probably not that big; PC got a much larger slowdown in comparison, and 2) Mac has a Haswell CPU with that 128MB of L4 cache which probably helps things a bit.

A side lesson from this might also be, even if your memory access patterns are completely linear & nice, they are still memory accesses. This does not happen often, but a couple times I’ve seen people approach for example multi-threading by going really heavy on “let’s pass buffers of data around, everywhere”. One might end up with a lot of buffers creating tons of additional memory traffic, even if the access pattern of each buffer is “super nice, linear, and full cache lines are being used”.

Anyway, right now this “buffer oriented” approach is actually quite a lot slower…

Let’s try to reduce ray data size

One possible approach to reduce memory traffic for the buffers would be to stop working on giant “full-screen, worst case capacity” buffers. We could work on buffers that are much smaller in size, and for example would fit into L1 cache; that probably would be a couple hundred rays per buffer.

So of course… let’s not do that for now :) and try to “just” reduce the amount of storage we need for one ray! “Why? We don’t ask why, we ask why not!”

Let’s go!

- There’s no need to track depth per-ray; we can just do the “process bounces” loop to max iterations instead (commit). Performance unchanged.

- Our

float3right now is an SSE-register size, which takes up space of four floats, not just the three we need. Stop doing that. Ray buffers: 1800→1350MB; PC performance: 66.1→89.9 Mray/s. - Instead of storing a couple ints and bools per ray, put all that into a 32 bit bitfield (commit). Ray buffers: 1350→1125MB; PC performance: 89.9→107 Mray/s.

- Change first ray bounce (camera rays); there’s little need to write all of them into buffer and immediately process them. They also don’t need to handle “current attenuation” bit (commit). PC performance: 107→133 Mray/s.

- You know what, ray directions and attenuation colors sound like they could use something more compact than a full

32 bit float per component. Let’s try to use 16 bit floats

(“half precision”) for them. And let’s use F16C CPU instructions to convert between

floatandhalf; these are generally available in Intel & AMD CPUs made since 2011. That’s these two commits (one and two). Ray buffers: 1125→787MB; PC performance: 107→156 Mray/s.

By the way, Mac performance has stayed at ~40 Mray/s across all these commits. Which makes me think that the bottleneck there is not the memory bandwidth, but calculations. But again, I haven’t investigated this further, just slapping that onto “eh, probably that giant L4 cache helps”.

Status and what’s next

Code is at 11-buffer-oriented tag

at github.

PC performance of the “buffer oriented” approach right now is at 156 Mray/s, which, while being behind the 187 Mray/s of the “recursion based” approach, is not “several times behind” at least. So maybe this buffer-oriented approach is not terribly bad, and I “just” need to make it work on smaller buffers that could nicely fit into the caches?

It would probably make sense to also split up “work to do per bounce” further, e.g. separate buffers for regular vs shadow rays; or even split up rays by material type, etc. Someday later!

I’m also interested to see what happens if I implement the above thing for the GPU compute shader variant. GPUs do tend to have massive memory bandwidth, after all. And the “process a big buffer in a fairly uniform way” might lead to way better GPU wave utilization. Maybe I’ll do that next.