Optimizing Unity Renderer Part 1: Intro

At work we formed a small “strike team” for optimizing CPU side of Unity’s rendering. I’ll blog about my part as I go (idea of doing that seems to be generally accepted). I don’t know where that will lead to, but hey that’s part of the fun!

Backstory / Parental Warning

I’m going to be harsh and say “this code sucks!” in a lot of cases. When trying to improve the code, you obviously want to improve what is bad, and so that is often the focus. Does not mean the codebase in general is that bad, or that it can’t be used for good things! Just this March, we’ve got Pillars of Eternity, Ori and the Blind Forest and Cities: Skylines among top rated PC games; all made with Unity. Not too bad for “that mobile engine that’s only good for prototyping”, eh.

The truth is, any codebase that grows over long period of time and is worked on by more than a handful of people is very likely “bad” in some sense. There are areas where code is weird; there are places that no one quite remembers how or why they work; there are decisions done many years ago that don’t quite make sense anymore, and no one had time to fix yet. In a big enough codebase, no single person can know all the details about how it’s supposed to work, so some decisions clash with some others in subtle ways. Paraphrasing someone, “there are codebases that suck, and there are codebases that aren’t used” :)

It is important to try to improve the codebase though! Always keep on improving it. We’ve done lots of improvements in all the areas, but frankly, the rendering code improvements over last several years have been very incremental, without anyone taking a hard look at the whole of it and focusing on just improving it as a fulltime effort. It’s about time we did that!

A number of times I’d point at some code and say “ha ha! well that is stupid!”. And it was me who wrote it in the first place. That’s okay. Maybe now I know better; or maybe the code made sense at the time; or maybe the code made sense considering the various factors (lack of time etc.). Or maybe I just was stupid back then. Maybe in five years I’ll look at my current code and say just as much.

Anyway…

Wishlist

In pictures, here’s what we want to end up with. A high throughput rendering system, working without bottlenecks.

Animated GIFs aside, here’s the “What is this?” section pretty much straight from our work wiki:

Current (Unity 5.0) rendering, shader runtime & graphics API CPU code is NotTerriblyEfficient(tm). It has several issues, and we want to address as much of that as possible:

- GfxDevice (our rendering API abstraction):

- Abstraction is mostly designed around DX9 / partially-DX10 concepts. E.g. constant/uniform buffers are a bad fit now.

- A mess that grew organically over many years; there are places that need a cleanup.

- Allow parallel command buffer creation on modern APIs (like consoles, DX12, Metal or Vulkan).

- Rendering loops:

- Lots of small inefficiencies and redundant decisions; want to optimize.

- Run parts of loops in parallel and/or jobify parts of them. Using native command buffer creation API where possible.

- Make code simpler & more uniform; factor out common functionality. Make more testable.

- Shader / Material runtime:

- Data layout in memory is, uhm, “not very good”.

- Convoluted code; want to clean up. Make more testable.

- “Fixed function shaders” concept should not exist at runtime. See [Generating Fixed Function Shaders at Import Time].

- Text based shader format is stupid. See [Binary Shader Serialization].

Constraints

Whatever we do to optimize / cleanup the code, we should keep the functionality working as much as possible. Some rarely used functionality or corner cases might be changed or broken, but only as a last resort.

Also one needs to consider that if some code looks complicated, it can be due to several reasons. One of them being “someone wrote too complicated code” (great! simplify it). Another might be “there was some reason for the code to be complex back then, but not anymore” (great! simplify it).

But it also might be that the code is doing complex things, e.g. it needs to handle some tricky cases. Maybe it can be simplified, but maybe it can’t. It’s very tempting to start “rewriting something from scratch”, but in some cases your new and nice code might grow complicated as soon as you start making it do all the things the old code was doing.

The Plan

Given a piece of CPU code, there are several axes of improving its performance: 1) “just making it faster” and 2) make it more parallel.

I thought I’d focus on “just make it faster” initially. Partially because I also want to simplify the code and remember the various tricky things it has to do. Simplifying the data, making the data flows more clear and making the code simpler often also allows doing step two (“make it more parallel”) easier.

I’ll be looking at higher level rendering logic (“rendering loops”) and shader/material runtime first, while others on the team will be looking at simplifying and sanitizing rendering API abstraction, and experimenting with “make it more parallel” approaches.

For testing rendering performance, we’re gonna need some actual content to test on. I’ve looked at several game and demo projects we have, and made them be CPU limited (by reducing GPU load - rendering at lower resolution; reducing poly count where it was very large; reducing shadowmap resolutions; reducing or removing postprocessing steps; reducing texture resolutions). To put higher load on the CPU, I duplicated parts of the scenes so they have way more objects rendered than originally.

It’s very easy to test rendering performance on something like “hey I have these 100000 cubes”, but that’s not a very realistic use case. “Tons of objects using exact same material and nothing else” is a very different rendering scenario from thousands of materials with different parameters, hundreds of different shaders, dozens of render target changes, shadowmap & regular rendering, alpha blended objects, dynamically generated geometry etc.

On the other hand, testing on a “full game” can be cumbersome too, especially if it requires interaction to get anywhere, is slow to load the full level, or is not CPU limited to begin with.

When testing for CPU performance, it helps to test on more than one device. I typically test on a development PC in Windows (currently Core i7 5820K), on a laptop in Mac (2013 rMBP) and on whatever iOS device I have around (right now, iPhone 6). Testing on consoles would be excellent for this task; I keep on hearing they have awesome profiling tools, more or less fixed clocks and relatively weak CPUs – but I’ve no devkits around. Maybe that means I should get one.

The Notes

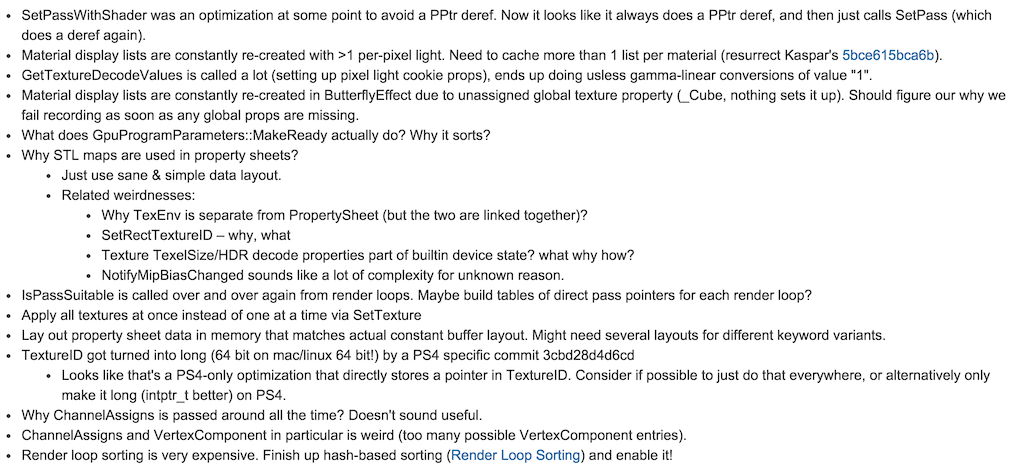

Next up, I ran the benchmark projects and looked at profiler data (both Unity profiler and 3rd party profilers like Sleepy/Instruments), and also looked at the code to see what it is doing. At this point whenever I see something strange I just write it down for later investigation:

Some of the weirdnesses above might have valid reasons, in which case I go and add code comments explaining them. Some might have had reasons once, but not anymore. In both cases source control log / annotate functionality is helpful, and asking people who wrote the code originally on why something is that way. Half of the list above is probably because I wrote it that way many years ago, which means I have to remember the reason(s), even if they are “it seemed like a good idea at the time”.

So that’s the introduction. Next time, taking some of the items from the above “WAT?” list and trying to do something about them!

Update: next blog post is up. Part 2: Cleanups.