Notes on Native Client & Pepper Plugin API

Google’s Native Client (NaCl) is a brilliant idea. TL;DR: it allows native code to be run securely in the browser.

But is it secure?

“Bububut, waitaminnit! Native code is not secure by definition” you say. Turns out, that isn’t necessarily true. With a specially massaged compiler, some runtime support and careful native code validation it is possible to ensure native code, when ran in the browser, can’t cause harm to user’s machine. I suggest taking a look at the original NaCl for x86 paper and more recently, how similar techniques would apply to ARM CPUs.

But what can you do with it?

So that’s great. It means it is possible to take C/C++ code, compile it with NaCl SDK (a gcc derived toolchain) and have it run in the browser. We can make a loop in C that multiplies a ton of floating point numbers, and it will run at native speed. That’s wonderful, except you can’t really do much interesting stuff with your own C code in isolation…

You need access to the hardware and/or OS. As game developers, we need pixels to appear on the screen. Preferably lots of them, with the help of something like a GPU. Audio waves to come out of the speakers. Mouse moves and keyboard presses to translate to some fancy actions. Post a high score to the internets. And so on.

NaCl surely can’t just allow my C code to call Direct3DCreate9 and run with it, while keeping the promise of “it’s secure”? Or a more extreme case, FILE* f = fopen("/etc/passwd", "rt");?!

And that’s true; NaCl does not allow you to use completely arbitrary APIs. It has it’s own set of APIs to interface with “the system”.

Ok, how do I interface with the system?

…and that’s where the current state of NaCl gets a bit confusing.

Initially Google developed an improved “browser plugin model” and called it Pepper. This Pepper thing would then take care of actually putting your code into the browser. Starting it up, tearing it down, controlling repaints, processing events and so on. But then apparently they realized that building on top of a decade-old Netscape plugin API (NPAPI) isn’t going to really work, so they developed Pepper2 or PPAPI (Pepper Plugin API) which ditches NPAPI completely. To write a native client plugin, you only interface with PPAPI.

So some of the pages on the internets reference the “old API” (which is gone as far as I can see), and some others reference the new one. It does not help that Native Client’s own documentation are scattered around in Chromium, NaCl, NaCl SDK and PPAPI sites. Seriously, it’s a mess, with seemingly no high level, up to date “introduction” page that tells what exactly PPAPI can and can’t do. Edit: I’m told that the definitive entry point to NaCl right now is this page: http://code.google.com/chrome/nativeclient/ which clears up some mess.

Here’s what I think it can do

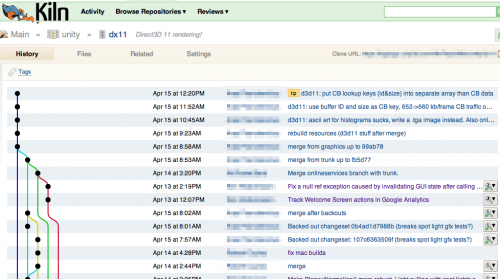

Note: At work we have an in-progress Unity NaCl port using this PPAPI. However, I am not working on it, so my knowledge may or may not be true. Take everything with a grain of NaCl ;)

Most of things below found by poking around at PPAPI source tree, and by looking into Unity’s NaCl platform dependent bits.

Graphics

PPAPI provides an OpenGL ES 2.0 implementation for your 3D needs. You need to setup the context and initial surfaces via PPAPI (ppapi/cpp/dev/context_3d_dev.h, ppapi/cpp/dev/surface_3d_dev.h) - similar to what you’d use EGL on other platforms for - and beyond that you just include GLES2/gl2.h, GLES2/gl2ext.h and call ye olde GLES2.0 functions.

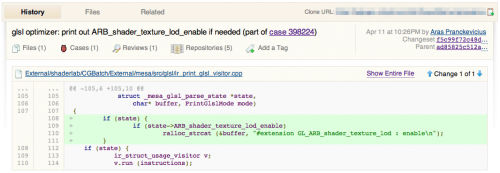

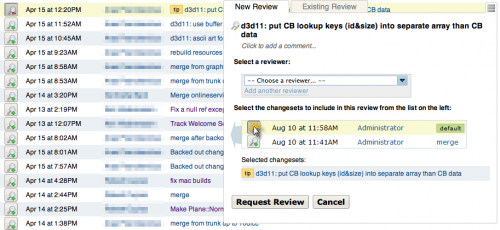

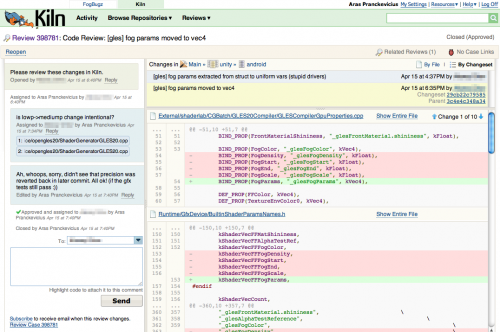

Behind the scenes, all your GLES2.0 calls will be put into a command buffer and transferred to actual “3D server” process for consuming them. Chrome splits up itself into various processes like that for security reasons – so that each process has the minimum set of privileges, and a crash or a security exploit in one of them can’t easily transfer over to other parts of the browser.

Audio

For audio needs, PPAPI provides a simple buffer based API in ppapi/cpp/audio_config.h and ppapi/cpp/audio.h. Your own callback will be called whenever audio buffer needs to be filled with new samples. That means you do all sound mixing yourself and just fill in the final buffer.

Input

Your plugin instance (subclass of pp::Instance) will get input events via HandleInputEvent virtual function override. Each event is a simple PPInputEvent struct and can represent keyboard & mouse. No support for gamepads or touch input so far, it seems.

Other stuff

Doing WWW requests is possible via ppapi/cpp/url_loader.h and friends.

Timer & time queries via ppapi/cpp/core.h (e.g. pp::Module::Get()->core()->CallOnMainThread(...)).

And, well, a bunch of other stuff is there, like ability to rasterize blocks of text into bitmaps, pop up file selection dialogs, use the browser to decode video streams and so on. Everything - or almost everything - is there to make it possible to do games on it.

Summary

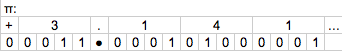

Like Chad says, it would be good to end “thou shalt only use Javascript” on the web. Javascript is a very nice language - especially considering how it came into existence - but forcing it on everyone is quite silly. And no matter how hard V8/JägerMonkey/Nitro folks are trying, it is very, very hard to beat performance of a simple, static, compiled language (like C) that has direct access to memory and the programmer is in almost full control of both the code flow and the memory layout. Steve rightly points out that even if for some tasks a super-optimized Javascript engine will approach the speed of C, it will burn much more energy to do so – a very important aspect in the increasingly mobile world.

Native Client does give some hope that there will be a way to run native code, at native speeds, in the browser, without compromising on security. Let it happen.