Vector math library codegen in Debug

This will be about how when in your C++ code you have a “vector math library”, and how the choices of code style in there affect non-optimized build performance.

Backstory

A month ago I got into the rabbit hole of trying to “sanitize” the various ways that images can be resized within Blender codebase. There were at least 4 different functions to do that, with different filtering modes (expected), but also different corner case behaviors and other funkiness, that was not well documented and not well understood.

I combed through all of that, fixed some arguably wrong behaviors of some of the functions, unified their behavior, etc. etc. Things got faster and better documented. Yay! (PR)

However. While doing that, I also made the code smaller, primarily

following the guideline of “code should use our C++ math library, not

the legacy C one”. That is, use Blender codebase classes like float4 with

related functions and operators (e.g. float4 c = a + b), instead of

float v[4] c; add_v4_v4v4(c, a, b); and so on. Sounds good? Yes!

But. There’s always a “but”.

Other developers later on noticed that some parts of Blender got slower, in non-optimized (“Debug”) build. Normally people say “oh it’s a Debug build, no one should care about performance of it”, and while in some cases it might be true, when anything becomes slower it is annoying.

In this particular case, it was “saving a file within Blender”. You see, as part of the saving process, it takes a screenshot of your application, resizes it to be smaller and embeds that as a “thumbnail” inside the file itself. And yes, this “resize it” part is exactly what my change affected. Many developers run their build in Debug mode for easier debugging and/or faster builds; some run it in Debug mode with Address Sanitizer on as well. If “save a file”, an operation that you normally do many times, became slower by say 2 seconds, that is annoying.

What can be done?

How Blender’s C++ math library is written today

It is pretty compact and neat! And perhaps too flexible :)

Base of the math vector types is this struct, with is just a fixed size array

of N entries. For the (most common) case of 2D, 3D and 4D vectors, the struct

is instead entries explicitly named x, y, z, w:

template<typename T, int Size>

struct vec_struct_base { std::array<T, Size> values; };

template<typename T> struct vec_struct_base<T, 2> { T x, y; };

template<typename T> struct vec_struct_base<T, 3> { T x, y, z; };

template<typename T> struct vec_struct_base<T, 4> { T x, y, z, w; };

And then it has functions and operators, where most of their implementations use an “unroll with a labmda” style. Here’s operator that adds two vectors together:

friend VecBase operator+(const VecBase &a, const VecBase &b)

{

VecBase result;

unroll<Size>([&](auto i) { result[i] = a[i] + b[i]; });

return result;

}

with unroll itself being this:

template<class Fn, size_t... I> void unroll_impl(Fn fn, std::index_sequence<I...>)

{

(fn(I), ...);

}

template<int N, class Fn> void unroll(Fn fn)

{

unroll_impl(fn, std::make_index_sequence<N>());

}

– it takes “how many times to do the lambda” (typically vector dimension), the lambda itself, and then “calls” the lambda with the index N times.

And then most of the functions use indexing operator to access the element of a vector:

T &operator[](int index)

{

BLI_assert(index >= 0);

BLI_assert(index < Size);

return reinterpret_cast<T *>(this)[index];

}

Pretty compact and hassle free. And given that C++ famously has “zero-cost abstractions”, these are all zero-cost, right? Let’s find out!

Test case

Let’s do some “simple” image processing code that does not serve a practical purpose, but is simple enough to test things out.

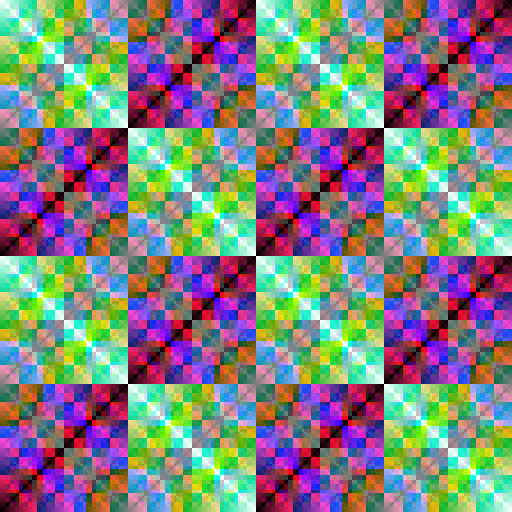

Given an input image (RGBA, byte per channel), blur it by averaging 11x11 square of pixels around each pixel, and overlay

a slight gradient over the whole image. This input, for example, gets turned into that output:

The filter code itself is this:

inline float4 load_pixel(const uint8_t* src, int size, int x, int y)

{

x &= size - 1;

y &= size - 1;

uchar4 bpix(src + (y * size + x) * 4);

float4 pix = float4(bpix) * (1.0f / 255.0f);

return pix;

}

inline void store_pixel(uint8_t* dst, int size, int x, int y, float4 pix)

{

pix = math_max(pix, float4(0.0f));

pix = math_min(pix, float4(1.0f));

pix = math_round(pix * 255.0f);

((uchar4*)dst)[y * size + x] = uchar4(pix);

}

void filter_image(int size, const uint8_t* src, uint8_t* dst)

{

const int kFilter = 5;

int idx = 0;

float blend = 0.2f;

float inv_size = 1.0f / size;

for (int y = 0; y < size; y++)

{

for (int x = 0; x < size; x++)

{

float4 pix(0.0f);

float4 tint(x * inv_size, y * inv_size, 1.0f - x * inv_size, 1.0f);

for (int by = y - kFilter; by <= y + kFilter; by++)

{

for (int bx = x - kFilter; bx <= x + kFilter; bx++)

{

float4 sample = load_pixel(src, size, bx, by);

sample = sample * (1.0f - blend) + tint * blend;

pix += sample;

}

}

pix *= 1.0f / ((kFilter * 2 + 1) * (kFilter * 2 + 1));

store_pixel(dst, size, x, y, pix);

}

}

}

This code uses very few vector math library operations: create a float4,

add them together, multiply them by a scalar, some functions to do min/max/round.

There are no branches (besides the loops themselves), no cross-lane swizzles, fancy

packing or anything like that.

Let’s run this code in the usual “Release” setting, i.e. optimized build (-O2 on gcc/clang,

/O2 on MSVC). Processing a 512x512 input image with the above filter, on Ryzen 5950X, Windows 10,

single threaded, times in milliseconds (lower is better):

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release (O2) | 67 | 41 | 45 | 70 | 70 |

Alright, Clang beats the others by a healthy margin here.

Enter Debug builds

At least within Blender (but also elsewhere), besides a build configuration that ships to the users, during development you often work with two or more other build configurations:

- “Debug”, which often means “the compiler does no optimizations at all” (

-O0on gcc/clang,/Odon MSVC). This is the least confusing debugging experience, since nothing is “optimized out” or “folded together”.- On MSVC, people also sometimes put

/JMC(“just my code” debugging), and that is default in recent MSVC project templates. Blender uses that too in the “Debug” cmake configuration.

- On MSVC, people also sometimes put

- “Developer”, which often is the same as “Release” but with some extra checks enabled. In Blender’s case,

besides things like “enable unit tests” and “use a guarded memory allocator”, it also enables assertion checks,

and in Linux/Mac also enables Address Sanitizer (

-fsanitize=address).

While some people argue that “Debug” build configuration should pay no attention to performance at all, I’m not sold on that argument. I’ve seen projects where a non-optimized code build, while it works, produces such bad performance that using the resulting application is an exercise in frustration. Some places explicitly enable some compiler optimizations on an otherwise “Debug” build, since otherwise the result is just unusable (e.g. in C++-heavy codebase, you’d enable function inlining).

However, the “Developer” configuration is an interesting one. It is supposed to be “optimized”, just with “some” extra safety features. I would normally expect that to be “maybe 5% or 10% slower” than the final “Release” build, but not more than that.

Let’s find out!

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release (O2) | 67 | 41 | 45 | 70 | 70 |

| Developer (O2 + asserts) | 591 | 42 | 45 | 71 | 71 |

Debug (-O0 / /Od /JMC) | 17560 | 4965 | 6476 | 5610 | 5942 |

Or, phrased in terms of “how many times a build configuration is slower compared to Release”:

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release (O2) | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Developer (O2 + asserts) | 9x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

Debug (-O0 / /Od /JMC) | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

On Developer config, gcc and clang are good: assertions being enabled does not cause a slowdown. On MSVC, however, this makes the code run 9 times slower. All of that

only because vector operator[](int index) has asserts in there. And it is only ever called with indices that are statically known to pass the asserts!

So much for an “optimizing compiler”, eh.

The Debug build configuration is just bad everywhere. Yes it is the worst on MSVC, but come on, anything that is more than 10 times slower than optimized code is going into “too slow to be practical” territory. And here we are talking about things being from 80 times to 250 times slower!

What can be done without changing the code?

Perhaps realizing that “no optimizations at all produce unusably slow result” is true, some compiler developers have added an “a bit optimized, yet still debuggable”

optimization level: -Og. GCC has added that in 2013 (gcc 4.8):

-Og should be the optimization level of choice for the standard edit-compile-debug cycle, offering a reasonable level of optimization while maintaining fast compilation and a good debugging experience.

Clang followed suit in 2017 (clang 4.0), however their -Og does

exactly the same thing as -O1.

MSVC has no setting like that, but we can at least try to turn off “just my code debugging” (/JMC) flag and see what happens. The slowdown table:

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release (O2) | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

Faster Debug (-Og / /Od) | 114x | 2x | 2x | 50x | 14x |

Debug (-O0 / /Od /JMC) | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

Alright, so:

- On clang

-Ogmakes the performance good. Expected since this is the same as-O1. - On gcc

-Ogis better than-O0. Curiously gcc 12 is slower than gcc 11 here for some reason. - MSVC without

/JMCis better, but still very very slow.

Can we change the code to be more Debug friendly?

Current way that the math library is written is short and concise. If you are used to C++ lambda syntax, things are very clear:

friend VecBase operator+(const VecBase &a, const VecBase &b)

{

VecBase result;

unroll<Size>([&](auto i) { result[i] = a[i] + b[i]; });

return result;

}

however, without compiler optimizations, for a float4 that produces (on clang):

- 18 function calls,

- 8 branches,

- assembly listing of 150 instructions.

What it actually does, is do four float additions.

Loop instead of unroll lambda

What about, if instead of this unroll+lambda machinery, we used just a simple loop?

friend VecBase operator+(const VecBase &a, const VecBase &b)

{

VecBase result;

for (int i = 0; i < Size; i++) result[i] = a[i] + b[i];

return result;

}

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release unroll | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Release loop | 1x | 1x | 1x | 3x | 10x |

| Developer unroll | 9x | ||||

| Developer loop | 1x | ||||

| Faster Debug unroll | 114x | 2x | 2x | 50x | 14x |

| Faster Debug loop | 65x | 2x | 2x | 31x | 14x |

| Debug unroll | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

| Debug loop | 126x | 102x | 108x | 58x | 58x |

This does help Debug configurations somewhat (12 function calls, 9 branches, 80 assembly instructions). However! It hurts Gcc code generation even in full Release mode 😱, so that’s probably a no-go. If it were not for the Gcc slowdown, it would be a win: better performance in Debug configuration, and a simple loop is easier to understand than a variadic template + lambda.

Explicit code paths for 2D/3D/4D vector cases

Out of all the possible vector math cases, 2D, 3D and 4D vectors are by far the most common. I’m not sure if other cases even happen within Blender codebase, TBH. Maybe we could specialize those to help the compiler a bit? For example:

friend VecBase operator+(const VecBase &a, const VecBase &b)

{

if constexpr (Size == 4) {

return VecBase(a.x + b.x, a.y + b.y, a.z + b.z, a.w + b.w);

}

else if constexpr (Size == 3) {

return VecBase(a.x + b.x, a.y + b.y, a.z + b.z);

}

else if constexpr (Size == 2) {

return VecBase(a.x + b.x, a.y + b.y);

}

else {

VecBase result;

unroll<Size>([&](auto i) { result[i] = a[i] + b[i]; });

return result;

}

}

This is very verbose and a bit typo-prone however :( With some C preprocessor help it can be reduced to hide most of the ugliness inside a macro, and then the actual operator implementation is not terribad:

friend VecBase operator+(const VecBase &a, const VecBase &b)

{

BLI_IMPL_OP_VEC_VEC(+);

}

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release unroll | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Release explicit | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Developer unroll | 9x | ||||

| Developer explicit | 1x | ||||

| Faster Debug unroll | 114x | 2x | 2x | 50x | 14x |

| Faster Debug explicit | 19x | 2x | 2x | 5x | 3x |

| Debug unroll | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

| Debug explicit | 55x | 18x | 30x | 22x | 21x |

This actually helps Debug configurations quite a lot! One downside is that you have to have a handful of C preprocessor macros to hide away all the complexity that specializes implementations for 2D/3D/4D vectors.

Not using C++ vector math, use C instead

As a thought exercise – what if instead of using the C++ vector math library, we went back to the C-style of writing code?

Within Blender, right now there’s guidance of “use C++ math library for new code, occasionally rewrite old code to use C++ math library” too. That makes the code more compact and easier to read for sure, but does it have any possible downsides?

Our test image filter code becomes this then (there’s no “math library” used then, just operations on numbers):

inline void load_pixel(const uint8_t* src, int size, int x, int y, float pix[4])

{

x &= size - 1;

y &= size - 1;

const uint8_t* ptr = src + (y * size + x) * 4;

pix[0] = ptr[0] * (1.0f / 255.0f);

pix[1] = ptr[1] * (1.0f / 255.0f);

pix[2] = ptr[2] * (1.0f / 255.0f);

pix[3] = ptr[3] * (1.0f / 255.0f);

}

inline void store_pixel(uint8_t* dst, int size, int x, int y, const float pix[4])

{

float r = std::max(pix[0], 0.0f);

float g = std::max(pix[1], 0.0f);

float b = std::max(pix[2], 0.0f);

float a = std::max(pix[3], 0.0f);

r = std::min(r, 1.0f);

g = std::min(g, 1.0f);

b = std::min(b, 1.0f);

a = std::min(a, 1.0f);

r = std::round(r * 255.0f);

g = std::round(g * 255.0f);

b = std::round(b * 255.0f);

a = std::round(a * 255.0f);

uint8_t* ptr = dst + (y * size + x) * 4;

ptr[0] = uint8_t(r);

ptr[1] = uint8_t(g);

ptr[2] = uint8_t(b);

ptr[3] = uint8_t(a);

}

void filter_image(int size, const uint8_t* src, uint8_t* dst)

{

const int kFilter = 5;

int idx = 0;

float blend = 0.2f;

float inv_size = 1.0f / size;

for (int y = 0; y < size; y++)

{

for (int x = 0; x < size; x++)

{

float pix[4] = { 0,0,0,0 };

float tint[4] = { x * inv_size, y * inv_size, 1.0f - x * inv_size, 1.0f };

for (int by = y - kFilter; by <= y + kFilter; by++)

{

for (int bx = x - kFilter; bx <= x + kFilter; bx++)

{

float sample[4];

load_pixel(src, size, bx, by, sample);

sample[0] = sample[0] * (1.0f - blend) + tint[0] * blend;

sample[1] = sample[1] * (1.0f - blend) + tint[1] * blend;

sample[2] = sample[2] * (1.0f - blend) + tint[2] * blend;

sample[3] = sample[3] * (1.0f - blend) + tint[3] * blend;

pix[0] += sample[0];

pix[1] += sample[1];

pix[2] += sample[2];

pix[3] += sample[3];

}

}

float scale = 1.0f / ((kFilter * 2 + 1) * (kFilter * 2 + 1));

pix[0] *= scale;

pix[1] *= scale;

pix[2] *= scale;

pix[3] *= scale;

store_pixel(dst, size, x, y, pix);

}

}

}

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release unroll | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Release C | 1x | 0.5x | 0.5x | 1x | 1x |

| Developer unroll | 9x | ||||

| Developer C | 1x | ||||

| Faster Debug unroll | 114x | 2x | 2x | 50x | 14x |

| Faster Debug C | 4x | 0.5x | 1.5x | 1x | 1x |

| Debug unroll | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

| Debug C | 5x | 6x | 6x | 4x | 4x |

Writing code in “pure C” style makes Debug build configuration performance really good! But the more interesting thing is… in Release build on clang, this is faster than C++ code. Even for this very simple vector math library, used on a very simple algorithm, C++ abstraction is not zero-cost!

What about SIMD?

In an ideal world, the compiler would take care of SIMD for us, especially in simple algorithms like the one being tested here. It is just number math, with very clear “four lanes” being operated on (maps perfectly to SSE or NEON registers), no complex cross-lane shuffles, packing or any of that stuff. Just some loops and some math.

Of course, as Matt Pharr writes in the excellent ISPC blog series, “Auto-vectorization is not a programming model” (post) (original quote by Theresa Foley).

What if we manually added template specializations to our math library, where for “type is float, dimension is 4” case it would just use SIMD intrinsics directly?

Note that this is not the right model if you want absolute best performance that also scales past 4-wide SIMD; the correct way would be to map one SIMD lane to one

“scalar item” in your algorithm. But that is a whole another topic; let’s limit ourselves to 4-wide SIMD and map a float4 to one SSE register:

template<> struct vec_struct_base<float, 4> { __m128 simd; };

template<>

inline VecBase<float, 4> operator+(const VecBase<float, 4>& a, const VecBase<float, 4>& b)

{

VecBase<float, 4> r;

r.simd = _mm_add_ps(a.simd, b.simd);

return r;

}

| MSVC 2022 | Clang 17 | Clang 14 | Gcc 12 | Gcc 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release unroll | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x | 1x |

| Release C | 1x | 0.5x | 0.5x | 1x | 1x |

| Release SIMD | 0.8x | 0.5x | 0.5x | 0.7x | 0.7x |

| Developer unroll | 9x | ||||

| Developer C | 1x | ||||

| Developer SIMD | 0.8x | ||||

| Faster Debug unroll | 114x | 2x | 2x | 50x | 14x |

| Faster Debug C | 4x | 0.5x | 1.5x | 1x | 1x |

| Faster Debug SIMD | 24x | 1.3x | 1.3x | 2x | 2x |

| Debug unroll | 262x | 121x | 144x | 80x | 85x |

| Debug C | 5x | 6x | 6x | 4x | 4x |

| Debug SIMD | 70x | 44x | 51x | 20x | 20x |

Two surprising things here:

- Even for this very simple case that sounds like “of course the compiler would perfectly vectorize this code, it is trivial!”, manually writing SIMD still wins everywhere except on Clang.

- However, in Debug build configuration, SIMD intrinsics incur heavy cost on performance, i.e. code is way slower than written in pure C scalar style. SIMD intrinsics are still better at performance than our intial code that uses unroll+lambda style.

What about O3 optimization level?

You say “hey you are using -O2 on gcc/clang, you should use -O3!” Yes I’ve tried that, and:

- On gcc it does not change anything, except fixes the curious “changing unroll lambda to a simple loop” problem, i.e. under

-O3there is no downside to using a loop in your vector math class compared to unroll+lambda. - On clang it makes the various C++ approaches from above almost reach the performance of either “raw C” or “SIMD” styles, but not quite.

What about “force inline”?

(Update 2024 Sep 17) Vittorio Romeo asked “what about using attributes that force inlining”? I don’t have a full table, but a quick summary is:

- In MSVC, that is not possible at all. Under

/Odnothing is inlined, even if you mark it as “force inline please”. There’s an open feature request to make that possible, but is not there (yet?). - In Clang force inline attributes help a bit, but not by much.

Learnings

All of the learnings are based on this particular code, which is “simple loops that do some simple pixel operations”. The learnings may or might not transfer to other domains.

- Clang feels like the best compiler of the three. Consistently fastest code, compared to other compilers, across various coding styles.

- “C++ has zero cost abstractions” (compared to raw C code) is not true, unless you’re on Clang.

- Debug build (no optimizations at all) performance of any C++ code style is really bad. The only way I could make it acceptable, while still being C++, is by specializing code for common cases, which I achieved by… using C preprocessor macros 🤦.

- It is not true that “MSVC has horrible Debug build performance”. Yes it is the worst of all of them, but the other compilers also produce really badly performing code in Debug build config.

- SIMD intrinsics in a non-optimized build have quite bad performance :(

- Using “enable some optimizations” build setting, e.g.

-Og, might be worth looking into, if your codebase is C++ and heavy on inlined functions, lambdas and that stuff. - Using “just my code debugging” (

/JMC) on Visual Studio has a high performance cost, on already really bad Debug build performance. I’m not sure if it is worth using at all, ever, anywhere.

All my test code of the above is in this tiny github repo, and a PR for Blender codebase

that does “explicitly specialize for common cased via C macros” is at #127577. Whether it will

get accepted is up in the air, since it does arguably make the code “more ugly” (the PR got merged into Blender mainline).