Backporting Fixes and Shuffling Branches

“Everyday I’m Shufflin’” – LMFAO

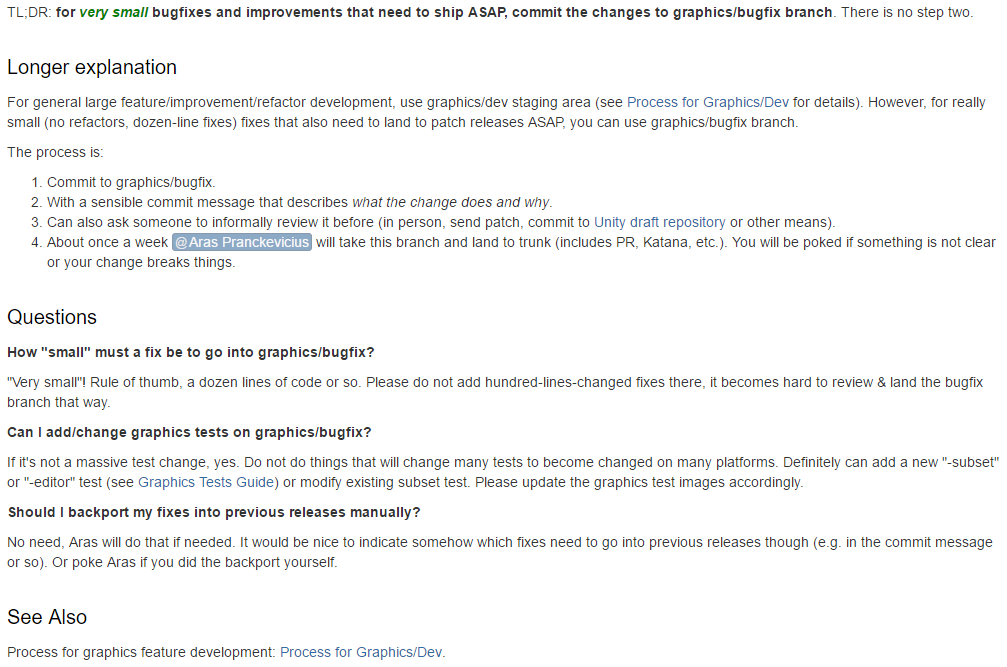

For past few months at work I’m operating this “graphics bugfixes” service. It’s a very simple, free (*) service that I’m doing to reduce overhead of doing “I have this tiny little fix there” changes. Aras-as-a-service, if you will. It works like explained in the image on the right.

(*) Where’s the catch? It’s free, so I’ll get a million people to use it, and then it’s a raging success! My plan is perfect.

Backporting vs Forwardporting Fixes

We pretty much always work on three releases at once: the “next” one (“trunk”, terminology back from Subversion source control days), the “current” one and the “previous” one. Right now these are:

- trunk: will become Unity 5.5 sometime later this year (see roadmap).

- 5.4: at the moment in fairly late beta, stabilization/polish.

- 5.3.x: initially released end of 2015, currently “long term support” release that will get fixes for many months.

Often fixes need to go into all three releases, sometimes with small adjustments. About the only workflow that has worked reliably here is: “make the fix in the latest release, backport to earlier as needed”. In this case, make the fix on trunk-based code, backport to 5.4 if needed, and to 5.3 if needed.

The alternative could be making the fix on 5.3, and forward porting to 5.4 & trunk. This we do sometimes, particularly for “zomg everything’s on fire, gotta fix asap!” type of fixes. The risk with this, is that it’s easy to “lose” a fix in the future releases. Even with best intentions, some fixes will be forgotten to be forward-ported, and then it’s embarrassing for everyone.

Shufflin’ 3 branches in your head can get confusing, doubly so if you’re also trying to get something else done. Here’s what I do.

1: Write Down Everything

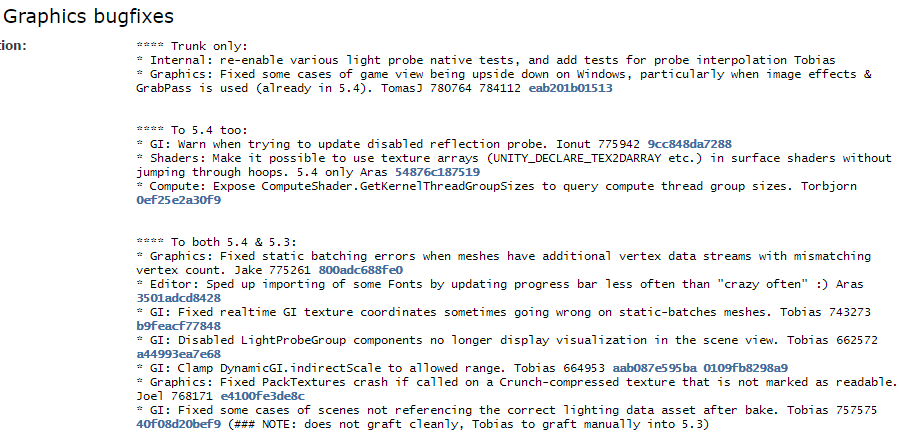

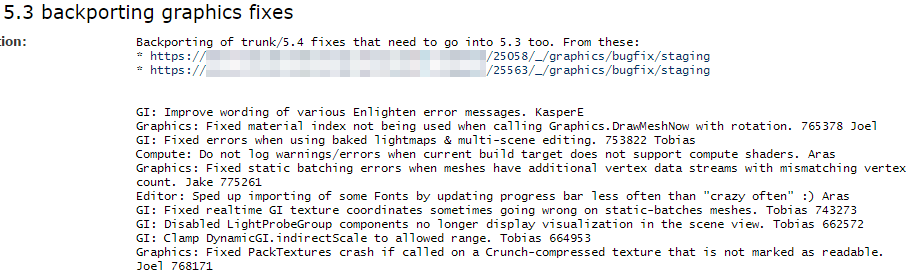

When making a rollup pull request of fixes to trunk, write down everything in the PR description.

- List of all fixes, with human-speak sentence of each (i.e. what would go into release notes). Sometimes a summary of commit message already has that, sometimes it does not. In the latter case, look at the fix and describe in simple words what it does (preferably from user’s POV).

- Separate the fixes that don’t need backporting, from the ones that need to go into 5.4 too, and the ones that need to go into both 5.4 and 5.3.

- Write down who made the fix, which bug case numbers it solves, and which code commits contain the fix (sometimes more than one!). The commits are useful later when doing actual backports; easier than trying to fish them out of the whole branch.

Here’s a fairly small bugfix pull request iteration with all the above:

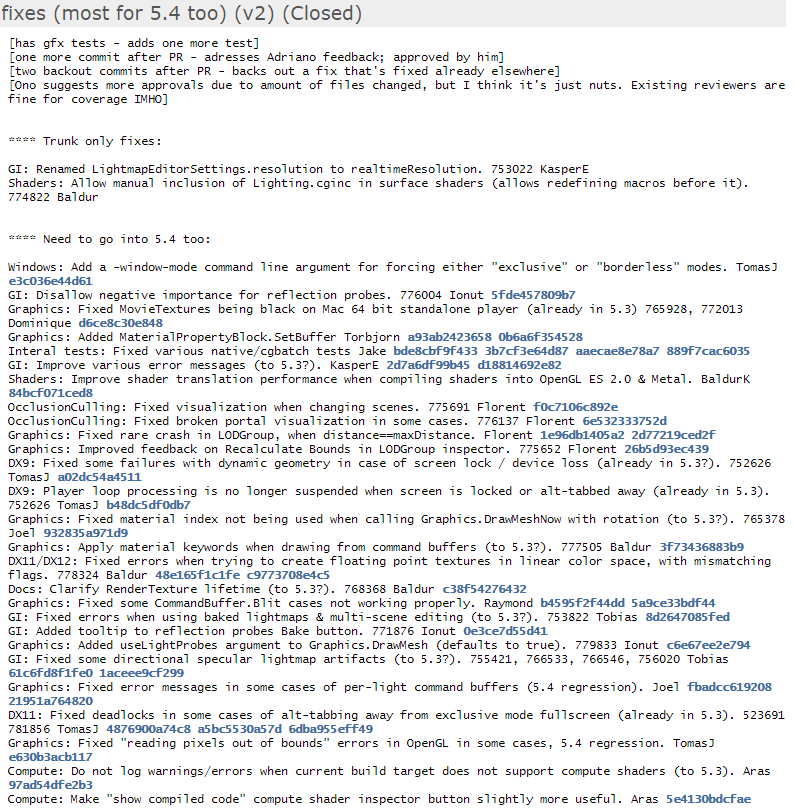

Nice and clean! However, some bugfix batches do end up quite messy; here’s the one that was quite involved. Too many fixes, too large fixes, too many code changes, hard to review etc.:

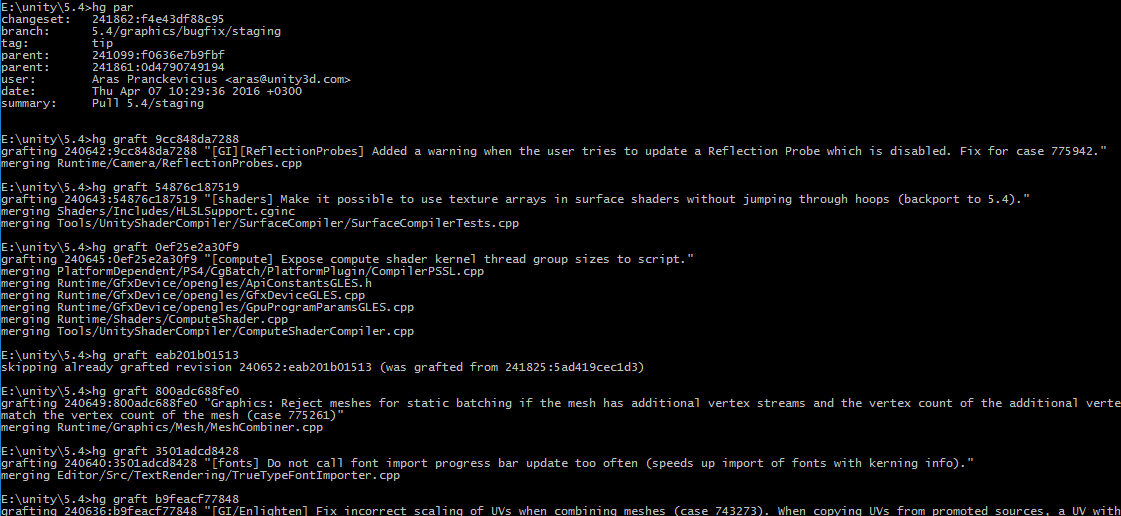

2: Do Actual Backporting

We’re using Mercurial, so this is mostly grafting commits between branches. This is where having commit hashes written down right next to fixes is useful.

Several situations can result when grafting things back:

- All fine! No conflicts no nothing. Good, move on.

- Turns out, someone already backported this (communication, it’s hard!). Good, move on.

- Easy conflicts. Look at the code, fix if trivial enough and you understand it.

- Complex conflicts. Talk with author of original fix; it’s their job to either backport manually now, or advise you how to fix the conflict.

As for actual repository organization, I have three clones of the codebase on my machine: trunk, 5.4, 5.3.

Was using a single repository and switching branches before, but it takes too long to do all the preparation

and building, particularly when switching between branches that are too far away from each other.

Our repository size is fairly big, so hg share extension

is useful - make trunk the “master” repository, and the other ones just working copies that share the same innards

of a .hg folder. SSDs appreciate 20GB savings!

3: Review After Backporting

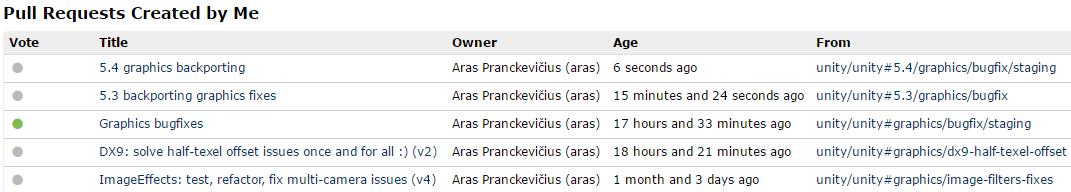

After all the grafting, create pull requests for 5.4 and 5.3, scan through the changes to make sure everything got through fine. Paste relevant bits into PR description for other reviewers:

And then you’re left with 3 or so pull requests, each against a corresponding release. In our case, this means potentially adding more reviewers for sanity checking, running builds and tests on the build farm, and finally merging them into actual release once everything is done. Dance time!

This is all.