The Virtual and No-Virtual

You are writing some system where different implementations have to be used for different platforms. To keep things real, let’s say it’s a rendering system which we’ll call “GfxDevice” (based on a true story!). For example, on Windows there could be a Direct3D 9, Direct3D 11 or OpenGL implementations; on iOS/Android there could be OpenGL ES 1.1 & 2.0 ones and so on.

For sake of simplicity, let’s say our GfxDevice interface needs to do this (in real world it would need to do much more):

void SetShader (ShaderType type, ShaderID shader);

void SetTexture (int unit, TextureID texture);

void SetGeometry (VertexBufferID vb, IndexBufferID ib);

void Draw (PrimitiveType prim, int primCount);

How this can be done?

Approach #1: virtual interface!

Many a programmer would think like this: why of course, GfxDevice is an interface with virtual functions, and then we have multiple implementations of it. Sounds good, and that’s what you would have been taught at the university in various software design courses. Here we go:

class GfxDevice {

public:

virtual ~GfxDevice();

virtual void SetShader (ShaderType type, ShaderID shader) = 0;

virtual void SetTexture (int unit, TextureID texture) = 0;

virtual void SetGeometry (VertexBufferID vb, IndexBufferID ib) = 0;

virtual void Draw (PrimitiveType prim, int primCount) = 0;

};

// and then we have:

class GfxDeviceD3D9 : public GfxDevice {

// ...

};

class GfxDeviceGLES20 : public GfxDevice {

// ...

};

class GfxDeviceGCM : public GfxDevice {

// ...

};

// and so on

And then based on platform (or something else) you create the right GfxDevice implementation, and the rest of the code uses that. This is all good and it works.

But then… hey! Some platforms can only ever have one GfxDevice implementation. On PS3 you will always end up using GfxDeviceGCM. Does it really make sense to have virtual functions on that platform?

Side note: of course the cost of a virtual function call is not something that stands out immediately. It’s much less than, for example, doing a network request to get the leaderboards or parsing that XML file that ended up in your game for reasons no one can remember. Virtual function calls will not show up in the profiler as “a heavy bottleneck”. However, they are not free and their cost will be scattered around in a million places that is very hard to eradicate. You can end up having death by a thousand paper cuts.

If we want to get rid of virtual functions on platforms where they are useless, what can we do?

Approach #2: preprocessor to the rescue

We just have to take out the “virtual” bit from the interface, and the “= 0” abstract function bit. With a bit of preprocessor we can:

#define GFX_DEVICE_VIRTUAL (PLATFORM_WINDOWS || PLATFORM_MOBILE_UNIVERSAL || SOMETHING_ELSE)

#if GFX_DEVICE_VIRTUAL

#define GFX_API virtual

#define GFX_PURE = 0

#else

#define GFX_API

#define GFX_PURE

#endif

class GfxDevice {

public:

GFX_API ~GfxDevice();

GFX_API void SetShader (ShaderType type, ShaderID shader) GFX_PURE;

GFX_API void SetTexture (int unit, TextureID texture) GFX_PURE;

GFX_API void SetGeometry (VertexBufferID vb, IndexBufferID ib) GFX_PURE;

GFX_API void Draw (PrimitiveType prim, int primCount) GFX_PURE;

};

And then there’s no separate class called GfxDeviceGCM for PS3; it’s just GfxDevice class implementing non-virtual methods. You have to make sure you don’t try to compile multiple GfxDevice class implementations on PS3 of course.

Ta-da! Virtual functions are gone on some platforms and life is good.

But we still have the other platforms, where there can be more than one GfxDevice implementation, and the decision for which one to use is made at runtime. Like our good old friend the PC: you could use Direct3D 9 or Direct3D 11 or OpenGL, based on the OS, GPU capabilities or user’s preference. Or a mobile platform where you don’t know whether OpenGL ES 2.0 will be available and you’d have to fallback to OpenGL ES 1.1.

Let’s think about what virtual functions actually are

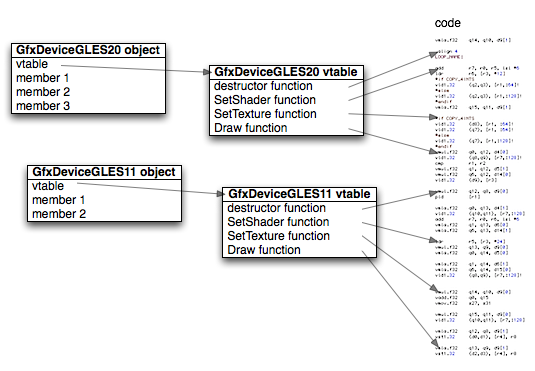

How virtual functions work? Usually they work like this: each object gets a “pointer to a virtual function table” as it’s first hidden member. The virtual function table (vtable) is then just pointers to where the functions are in the code. Something like this:

The key points are: 1) each object’s data starts with a vtable pointer, and 2) vtable layout for classes implementing the same interface is the same.

When the compiler generates code for something like this:

device->Draw (kPrimTriangles, 1337);

it will generate something like the following pseudo-assembly:

vtable = load pointer from [device] address

drawlocation = vtable + 3*PointerSize ; since Draw is at index [3] in vtable

drawfunction = load pointer from [drawlocation] address

pass device pointer, kPrimTriangles and 1337 as arguments

call into code at [drawfunction] address

This code will work no matter if device is of GfxDeviceGLES20 or GfxDeviceGLES11 kind. For both cases, the first pointer in the object will point to the appropriate vtable, and the fourth pointer in the vtable will point to the appropriate Draw function.

By the way, the above illustrates the overhead of a virtual function call. If we’d assume a platform where we have an in-order CPU and reading from memory takes 500 CPU cycles (which is not far from truth for current consoles), then if nothing we need is in the CPU cache yet, this is what actually happens:

vtable = load pointer from [device] address

; *wait 500 cycles* until the pointer arrives

drawlocation = vtable + 3*PointerSize

drawfunction = load pointer from [drawlocation] address

; *wait 500 cycles* until the pointer arrives

pass device pointer, kPrimTriangles and 1337 as arguments

call into code at [drawfunction] address

; *wait 500 cycles* until code at that address is loaded

Can we do better?

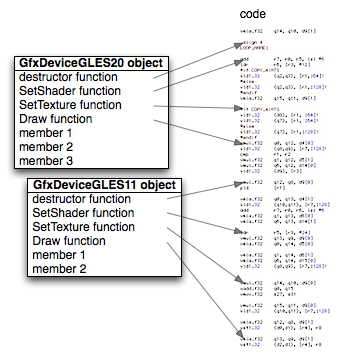

Look at the picture in the previous paragraph and remember the “wait 500 cycles” for each pointer we are chasing. Can we reduce the number of pointer chases? Of course we can: why not ditch the vtable altogether, and just put function pointers directly into the GfxDevice object?

Virtual tables are implemented in this way mostly to save space. If we had 10000 objects of some class that has 20 virtual methods, we only pay one pointer overhead per object (40000 bytes on 32 bit architecture) and we store the vtable (20*4=80 bytes on 32 bit arch) just once, in total 39.14 kilobytes.

If we’d move all function pointers into objects themselves, we’d need to store 20 function pointers in each object. Which would be 781.25 kilobytes! Clearly this approach does not scale with increasing object instance counts.

However, how many GfxDevice object instances do we really have? Most often… exactly one.

Approach #3: function pointers

If we move function pointers to the object itself, we’d have something like this:

There’s no built-in language support for implementing this in C++ however, so that would have to be done manually. Something like:

struct GfxDeviceFunctions {

SetShaderFunc SetShader;

SetTextureFunc SetTexture;

SetGeometryFunc SetGeometry;

DrawFunc Draw;

};

class GfxDeviceGLES20 : public GfxDeviceFunctions {

// ...

};

And then when creating a particular GfxDevice, you have to fill in the function pointers yourself. And the functions were member functions which magically take “this” parameter; it’s hard to just use them as function pointers without going to clumsy C++ member function pointer syntax and related issues.

We can be more explicit, C style, and instead just have the functions be static, taking “this” parameter directly:

class GfxDeviceGLES20 : public GfxDeviceFunctions {

// ...

static void DrawImpl (GfxDevice* self, PrimitiveType prim, int primCount);

// ...

};

Code that uses it would look like this then:

device->Draw (device, kPrimTriangles, 1337);

and it would generate the following pseudo-assembly:

drawlocation = device + 3*PointerSize

drawfunction = load pointer from [drawlocation] address

; *wait 500 cycles* until the pointer arrives

pass device pointer, kPrimTriangles and 1337 as arguments

call into code at [drawfunction] address

; *wait 500 cycles* until code at that address is loaded

Look at that, one of “wait 500 cycles” is gone!

More C style

We could move function pointers outside of GfxDevice if we want to, and just make them global:

In GLES1.1 case, that global GfxDevice funcs block would point to different pieces of code. And the pseudocode for this:

// global variables!

SetShaderFunc GfxSetShader;

SetTextureFunc GfxSetTexture;

SetGeometryFunc GfxSetGeometry;

DrawFunc GfxDraw;

// GLES2.0 implementation:

void GfxDrawGLES20 (GfxDevice* self, PrimitiveType prim, int primCount) { /* ... */ }

Code that uses it:

GfxDraw (device, kPrimTriangles, 1337);

and the pseudo-assembly:

drawfunction = load pointer from [GfxDraw variable] address

; wait 500 cycles until the pointer arrives

pass device pointer, kPrimTriangles and 1337 as arguments

call into code at [drawfunction] address

; wait 500 cycles until code at that address is loaded

Is it worth it?

I can hear some saying, “what? throwing away C++ OOP and implementing the same in almost raw C?! you’re crazy!”

Whether going the above route is better or worse is mostly a matter of programming style and preferences. It does get rid of one “wait 500 cycles” in the worst case for sure. And yes, to get that you do lose some of automagic syntax sugar in C++.

Is it worth it? Like always, depends on a lot of things. But if you do find yourself pondering the virtual function overhead for singleton-like objects, or especially if you do see that your profiler reports cache misses when calling into them, at least you’ll know one of the many possible alternatives, right?

And yeah, another alternative that’s easy to do on some platforms? Just put different GfxDevice implementations into dynamically loaded libraries, exposing the same set of functions. Which would end up being very similar to the last approach of “store function pointer table globally”, except you’d get some compiler syntax sugar to make it easier; and you wouldn’t even need to load the code that is not going to be used.