Hash Functions all the way down

Update! I tested more hash functions in a follow-up post. See More Hash Function Tests.

A while ago I needed fast hash function for ~32 byte keys. We already had MurmurHash used in a bunch of places, so I started with that. But then I tried xxHash and that was a bit faster! So I dropped xxHash into the codebase, landed the thing to mainline and promptly left for vacation, with a mental note of “someday should look into other hash functions, or at least move them all under a single folder”.

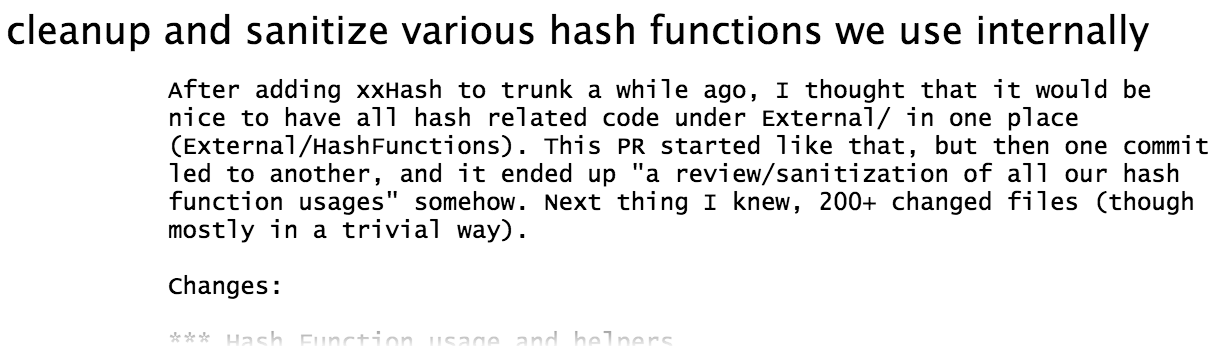

So that’s what I did: “hey I’ll move source code of MurmurHash, SpookyHash and xxHash under a single place”. But that quickly spiraled out of control:

The things I found! Here’s what you find in a decent-sized codebase, with many people working on it:

- Most places use a decent hash function – in our case Murmur2A for 32/64 bit hashes, and SpookyV2 for 128 bit hashes. That’s not a bad place to be in!

- Murmur hash takes seed as input, and naturally almost all places in code copy-pasted the same random hex value as the seed :)

- There are at least several copies of either FNV or djb2 hash function implementations scattered around, used in random places.

- Some code uses really, REALLY bad hash functions. There’s even a comment above it, added a number of years ago, when someone found out it’s bad – however they only stopped using it in their own place, and did not replace other usages. Life always takes the path of least resistance :) Thankfully, the places where said hash function was used were nothing “critical”.

- While 95% of code that uses non-cryptographic hash functions uses them strictly for runtime reasons (i.e. they don’t actually care about exact value of the hash), there are some pieces that hash something, and serialize the hashed value. Each of these need to be looked at in detail, whether you can easily switch to a new hash function.

- Some other hash related code (specifically, a struct we have to hold 128 bit hashed value,

Hash128), were written in a funky way, ages ago. And of course some of our code got that wrong (thankfully, all either debug code, or test mocking code, or something not-critical). Long story short, do not have struct constructors like this:Hash128(const char* str, int len=16)!- Someone will think this accepts a string to hash, not “bytes of the hash value”.

- Someone will pass

"foo"into it, and not provide length argument, leading to out-of-bounds reads. - Some code will accidentally pass something like

0to a function that accepts a Hash128, and because C++ is C++, this will get turned into aHash128(NULL, 16)constructor, and hilarity will ensue. - Lesson: be careful with implicit constructors (use

explicit). Be careful with default arguments. Don’t set types toconst char*unless it’s really a string.

So what started out as “move some files” branch, ended up being a “move files, switch most of hash functions, remove some bad hash functions, change some code, fix some wrong usages, add tests and comments” type of thing. It’s a rabbit hole of hash functions, all the way down!

Anyway.

Hash Functions. Which one to use?

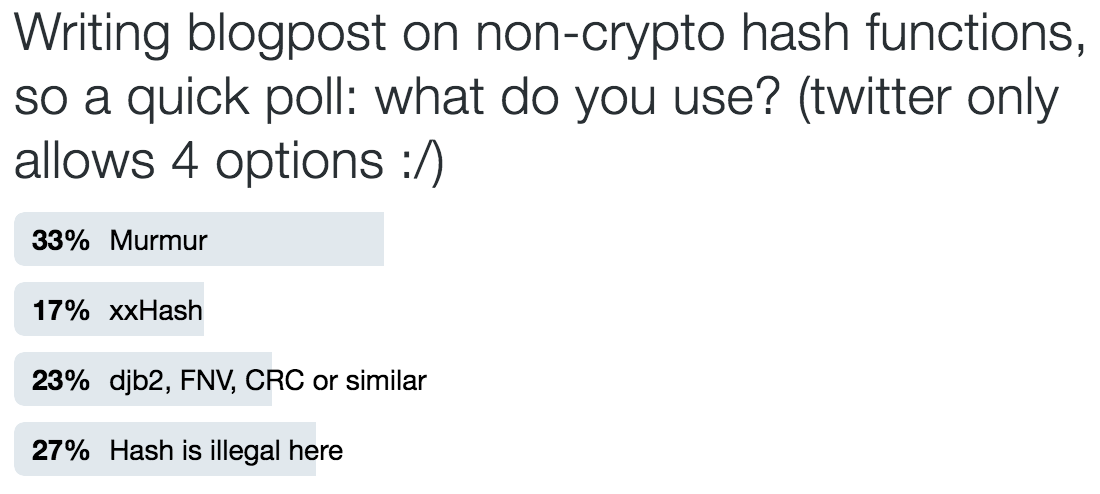

MurmurHash got quite popular, at least in game developer circles, as a “general hash function”. My quick twitter poll seems to reflect that:

It’s a fine choice, but let’s see later if we can generally do better. Another fine choice, especially if you know more about your data than “it’s gonna be an unknown number of bytes”, is to roll your own (e.g. see Won Chun’s replies, or Rune’s modified xxHash/Murmur that are specialized for 4-byte keys etc.). If you know your data, always try to see whether that knowledge can be used for good effect!

Sometimes you don’t know much about the data, for example if you’re hashing arbitrary files, or some user input that could be “pretty much anything”.

So let’s take a look at general purpose hash functions. There’s plenty of good tests on the internets (e.g. Hash functions: An empirical comparison), but I wanted to make my own little tests. Because why not! Here’s my randomly mashed together little testbed (use revision 4d535b).

Throughput

Here’s results of various hash functions, hashing data of different lengths, with performance in MB/s:

This was tested on late 2013 MacBookPro (Core i7-4850HQ 2.3GHz), Xcode 7.3.1 release 64 bit build.

- xxHash in 32 and 64 bit variants, as well as “use 64 bit, take lowest 32 bits of result” one.

- SpookyHash V2, the 128 bit variant, only taking 64 lowest bits.

- Murmur, a couple variants of it.

- CRC32, FNV and djb2, as I found them in our own codebase. I did not actually check whether they are proper implementations or somehow tweaked! Their source is at the testbed, revision 4d535b.

In terms of throughput at not-too-small data sizes (larger than 10-20 bytes), xxHash is the king. If you need 128 bit hashes, SpookyHash is very good too.

What about small keys?

Good question! The throughput of XXH64 is achieved by carefully exploiting instruction level parallelism of modern CPUs. It has a main loop that does 32 bytes at a time, with four independent hashing rounds. It looks something like this:

// rough outline of XXH64:

// ... setup code

do {

v1 = XXH64_round(v1, XXH_get64bits(p)); p+=8;

v2 = XXH64_round(v2, XXH_get64bits(p)); p+=8;

v3 = XXH64_round(v3, XXH_get64bits(p)); p+=8;

v4 = XXH64_round(v4, XXH_get64bits(p)); p+=8;

} while (p<=limit);

// ... merge v1..v4 values

// ... do leftover bit that is not multiple of 32 bytes

That way even if it looks like it’s “doing more work”, it ends up being faster than super simple algorithms like FNV, that work on one byte at a time, with each and every operation depending on the result of the previous one:

// rough outline of FNV:

while (*c)

{

hash = (hash ^ *c++) * p;

}

However, xxHash has all this “prologue” and “epilogue” code around the main loop, that handles either non-aligned data, or leftovers from data that aren’t multiple of 32 bytes in size. That adds some branches, and for short keys it does not even go into that smart loop!

That can be seen from the graph above, e.g. xxHash 32 (which has core loop of 16-bytes-at-once) is faster at key sizes < 100 bytes. Let’s zoom in at even smaller data sizes:

Here (data sizes < 10 bytes) we can see that the ILP smartness of other algorithms does not get to show itself, and the super-simplicity of FNV or djb2 win in performance. I’m picking out FNV as the winner here, because in my tests djb2 had somewhat more collisions (see below).

What about other platforms?

PC/Windows: tests I did on Windows (Core i7-5820K 3.3GHz, Win10, Visual Studio 2015 release 64 bit) follow roughly the same pattern as the results on a Mac. Nothing too surprising here.

Consoles: did a quick test on XboxOne. Results are surprising in two ways: 1) oh geez the console CPUs are slow (well ok that’s not too surprising), and 2) xxHash is not that awesome here. It’s still decent, but xxHash64 has consistenly worse performance than xxHash32, and for larger keys SpookyHash beats them all. Maybe I need to tweak some settings or poke Yann to look at it? Adding a mental note to do that later…

Mobile: tested on iPhone 6 in 64 bit build. Results not too surprising, except again, unlike PC/Mac with an Intel CPU, xxHash64 is not massively better than everything else – SpookyHash is really good on ARM64 too.

JavaScript! :) Because it was easy, I also compiled that code into asm.js via Emscripten. Overall the patterns are similar, except the >32 bit hashes (xxHash64, SpookyV2) – these are much slower. This is expected, both xxHash64 and Spooky are specifically designed either for 64 bit CPUs, or when you absolutely need a >32 bit hash. If you’re on 32 bit, use xxHash32 or Murmur!

What about hash quality?

SMHasher seems to be a de-facto hash function testing suite (see also: a fork that includes more modern hash functions).

For a layman test, I tested several things on data sets I cared about:

- “Words” - just a dump of English words (

/usr/share/dict/words). 235886 entries, 2.2MB total size, average length 9.6 bytes. - “Filenames” - dump of file paths (from a Unity source tree tests folder). 80297 entries, 4.3MB total size, average length 56.4 bytes.

- “Source” - partial dump of source files from Unity source tree. 6069 entries, 43.7MB total size, average length 7547 bytes.

First let’s see how many collisions we’d get on these data sets, if we used the hash function for uniqueness/checksum type of checking. Lower numbers are better (0 is ideal):

| Hash | Words collis | Filenames collis | Source collis |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxHash32 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| xxHash64-32 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| xxHash64 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SpookyV2-64 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Murmur2A | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Murmur3-32 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| CRC32 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| FNV | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| djb2 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| ZOMGBadHash | 998 | 842 | 0 |

ZOMGBadHash is that fairly bad hash function I found, as mentioned above. It’s not fast either, and look at that number of collisions!

Here’s how it looked like:

unsigned CStringHash(const char* key)

{

unsigned h = 0;

const unsigned sr = 8 * sizeof (unsigned) - 8;

const unsigned mask = 0xFu << (sr + 4);

while (*key != '\0')

{

h = (h << 4) + *key;

std::size_t g = h & mask;

h ^= g | (g >> sr);

key++;

}

return h;

}

I guess someone thought a random jumbo of shifts and xors is gonna make a good hash function, or something. And thrown in mixed 32 vs 64 bit calculations too, for good measure. Do not do this! Hash functions are not just random bit operations.

As another measure of “hash quality”, let’s imagine we use the hash functions in a hashtable. A typical hashtable of a load factor 0.8,

that always has power-of-two number of buckets (i.e. something like bucketCount = NextPowerOfTwo(dataSetSize / 0.8)). If we’d put

the above data sets into this hashtable, then how many entries we’d have per bucket on average? Lower numbers are better (1.0 is ideal):

| Hash | Words avg bucket | Filenames avg bucket | Source avg bucket |

|---|---|---|---|

| xxHash32 | 1.241 | 1.338 | 1.422 |

| xxHash64-32 | 1.240 | 1.335 | 1.430 |

| xxHash64 | 1.240 | 1.335 | 1.430 |

| SpookyV2-64 | 1.241 | 1.336 | 1.434 |

| Murmur2A | 1.239 | 1.340 | 1.430 |

| Murmur3-32 | 1.242 | 1.340 | 1.427 |

| CRC32 | 1.240 | 1.338 | 1.421 |

| FNV | 1.243 | 1.339 | 1.415 |

| djb2 | 1.242 | 1.339 | 1.414 |

| ZOMGBadHash | 1.633 | 2.363 | 7.260 |

Here all the hash functions are very similar, except the ZOMGBadHash which is, as expected, doing not that well.

TODO

I did not test some of the new-ish hash functions (CityHash, MetroHash, FarmHash). Did not test hash functions that use CPU specific instructions either (for example variants of FarmHash can use CRC32 instruction that’s added in SSE4.2, etc.). That would be for some future time.

Conclusion

- xxHash64 is really good, especially if you’re on an 64 bit Intel CPU.

- If you need 128 bit keys, use SpookyHash. It’s also really good if you’re on a non-Intel 64 bit CPU (as shown by XboxOne - AMD and iPhone6 - ARM throughput tests).

- If you need a 32 bit hash, and are on a 32 bit CPU/system, do not use xxHash64 or SpookyHash! Their 64 bit math is costly when on 32 bit; use xxHash32 or Murmur.

- For short data/strings, simplicity of FNV or djb2 are hard to beat, they are very performant on short data as well.

- Do not throw in random bit operations and call that a hash function. Hash function quality is important, and there’s plenty of good (and fast!) hash functions around.

Note: I tested more hash functions in a follow-up post. See More Hash Function Tests.